Foreword

Fergus Fleming

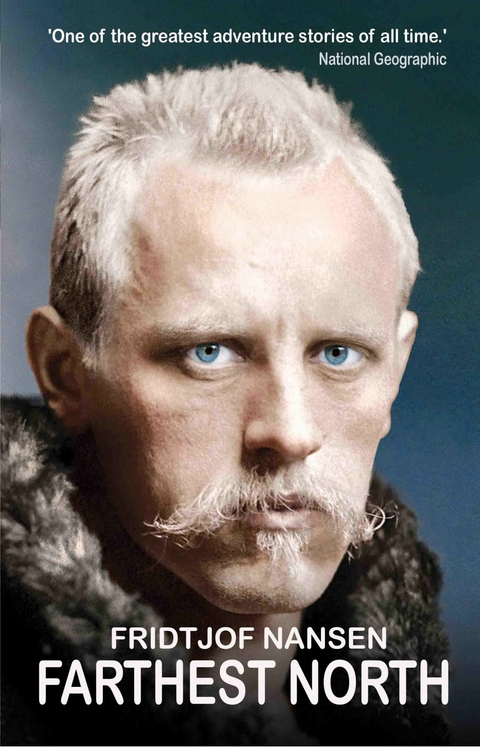

By 1890 governments in Europe and America were sick of the North Pole. They had been trying to reach it for so long; the race had cost so much in terms of money and lives; and, frankly, what was the point of it? Wild fantasies abounded as to what lay there — a continent, a sea, a hole leading to the centre of the globe — but if it was nothing save a sheet of empty ice, as an increasing number suspected was the case, then further expeditions were futile; science could be served equally profitably and far more safely by the ring of Arctic observatories that had been set up in the International Polar Year of 1882. Anyway, the question was hypothetical because the North Pole was unattainable. Certain individuals thought otherwise. Between 1894 and 1914 they launched repeated expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic, raising funds where they could find them and utilising every new piece of technology as it became available. Their exploits, which climaxed with the conquest of the North Pole by Robert Peary in 1909 (so he said) and that of the South Pole by Roald Amundsen in 1911, were a triumph of private enterprise over public intervention. But they were also a triumph of sensationalism over sense — all too often the desire for fame resulted in death and disaster. It was a peculiarly driven era, marked by examples of courage and incompetence, failure and success, fierce individualism and hamfisted planning, wild dreams and sober assessments. Historians have dubbed it the Age of Heroes; and they credit Fridtjof Nansen as its inaugurator.

Nansen never particularly wanted to be a polar explorer. Born on 10 October 1861, he was by training a neuroscientist — rather a good one: certain nerves still bear his name — but he came to prominence in 1888 when, on a whim, and to prove that traditional man-hauled sledging methods were wrong, he used skis to make the first crossing of Greenland’s ice cap. Thereafter he was infected by what 19th-century writers called “the Arctic virus.” As he apologised to an inquirer in 1892, “It is rather more accidental circumstances that have forced me into this line… A great many plans and ideas how to explore the unknown Arctic regions have forced themselves upon my mind almost without my help and will, and now I think it my duty to try whether they are not right (as I feel convinced they are) though it is almost with pain that I think of my microscope and my histological work.” On 24 June 1893, he sailed aboard the Fram from Christiania (modern Oslo) to put his plans to the test.

The voyage of the Fram was the most audacious and most successful polar experiment of Victorian times. From 1894 to 1896, its meander through the pack produced data on weather patterns, currents, and undersea topography; it demonstrated that a vessel need not sink when caught in the ice, that its daily energy requirements could be provided by windpower instead of steam, and that Europeans could actually survive for prolonged periods in the Arctic without succumbing to scurvy — though it demonstrated the latter by accident: Nansen’s success lay in adopting a varied diet; but until the discovery in the 20th century of Vitamin C nobody could explain which element in his diet had kept the disease at bay. According to one expert, the Fram’s journey constituted, “almost as great an advance as has been accomplished by all other voyages in the nineteenth century put together.”

The voyage also provided one of the great epics of polar exploration. In March 1895 Nansen left the Fram to its devices and, with crewmember Hjalmar Johansen, skied towards the North Pole with dog-drawn sledges and kayaks. Their plan was to press north until their supplies began to run out and then, eating the dogs as they became redundant, retreat to Franz Josef Land where they would hitch a ride home on a whaling ship or, failing that, sail in their kayaks to Norway or Spitsbergen. The first part of the plan was sound; the second was hare-brained: there was no certainty of meeting a whaler, and their kayaks would have been swamped had they ever tried to cross the ocean. It was sheer luck that they were rescued by Frederick Jackson, a British explorer who happened to be on Franz-Josef Land in June 1896. As Jackson later said, “I can positively state that not a million to one chance of Nansen ever reaching Europe existed, and, but for our finding him on the ice, as we did, the world would never have heard of him again.” Yet, despite his foolhardiness, Nansen had travelled farther north than any human being and had managed to survive fifteen months in the Arctic, almost five of which had been on the pack. When he returned to Norway he was hailed as “a Man in a Million.”

Farthest North is the book that describes his odyssey. It took just two months to write — an unbelievably swift time — and was illustrated by Nansen’s own drawings and photographs. (For those interested in the history of polar images, it is worth recording that Nansen’s composition for a meal aboard the Fram was later copied by both Shackleton and Scott.) The journal was an immediate best-seller both in Scandinavia and the rest of Europe. On its publication, Nansen became an international hero, fêted by geographical societies around the world. He had solved the great question: although he had not reached the Pole itself, he had ascertained that it was almost certainly ice and the “international steeple-chase,” as one Austrian called it, could now cease.

Of, course, it did not cease. Nansen’s example merely fired people to greater endeavour. He became a role model whose methods and equipment were widely copied. In both the Arctic and Antartcic, explorers used Nansen skis, Nansen sledges and Nansen kayaks. They used the Nansen method of travelling with a minimum of men, and adopted the Nansen principle of employing dogs both as beasts of burden and a source of food. They also benefited from Nansen’s pioneering use of technology, such as the unsinkable Fram and the energy-efficient Primus stove. Popular too, in some circles, were his Jaeger woollens — albeit, furs were far better suited to polar conditions. That he set the standard for polar exploration was evident in the titles of subsequent journals: Peary’s Nearest the Pole, for example, was an unsubtle piece of leg- cocking; even more blatant was the Duke of Abruzzi’s Farther North Than Nansen. Later in life he would be described by the polar aeronaut Richard Evelyn Byrd as the “Great Dean of Arctic Exploration.”

Nansen was certainly the first, and possibly the most outstanding, hero of the age. His achievement, although flawed, was rarely matched by his successors — his acolyte and fellow Norwegian, Roald Amundsen, being a notable exception. And it was not matched for this reason: he had set himself a goal, he had attained it, and, importantly, he had done so without the loss of a single life. Against his success, however, must be set his failings. Although a good planner he was an erratic leader. His charisma was powerful — “I have never met anyone who had such a magnetic personality, and such a profound confidence in himself,” wrote one of Jackson’s team in awe — but it was often too strong for comfort. His moods swung from introspection to exultation, marked at either extreme by references to the Nordic gods with whom he identified. He was domineering and at times intolerant. When he left the Fram most of the crew were only too happy to see him go. Hjalmar Johansen, who endured his company for some fifteen months, found him stiff and unapproachable: “He is too self-centred to be anybody’s friend and one’s patience is sorely tried,” he wrote. “It is silent in the tent; no fun, never a joke. The fellow is unsociable and clumsy in the smallest things; egoistic in the highest degree.” To give Nansen his due, Johansen seems to have been an equally miserable companion. (In 1911 he was given a place on Amundsen’s South Pole expedition but was left at base camp because of his awkwardness. He later shot himself, in a fit of depression.) Nevertheless, such accusations could not have been levelled against contemporaries such as Peary, Scott or Shackleton.

Nansen made his name from the Fram expedition but, as his biographer Roland Huntford has shown, to view him solely in terms of exploration would be to categorise him unfairly. He toyed with the idea of returning to the ice — he wondered if the methods he had pioneered might be used to take the South Pole (Amundsen did it for him) or if he should fly to the North Pole (Amundsen, again, did it) — but, really, he was not that interested. Unlike his fellow heroes, who tended towards monomania, Nansen was a man of multifarious talents. He was a geologist and a ground-breaking oceanographer. He developed theories about tectonic shift and was one of the first to associate sun spots with climate change. His neurological research was drawn upon by the winners of the 1906 Nobel Prize...