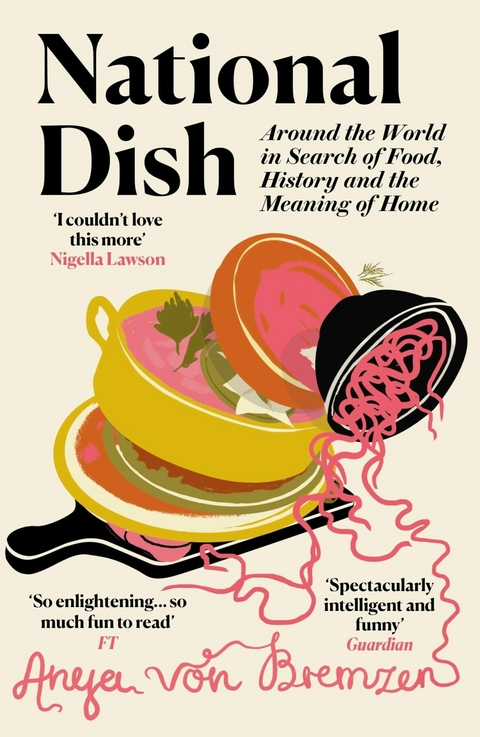

National Dish (eBook)

'This voyage into culinary myth-making and identity is essential reading. Its breadth of scope and scholarship is conveyed with such engaging wit. I couldn't love it more' Nigella Lawson

'A truly captivating and evocative book. National Dish takes you on a food journey written with real warmth, wit and perception' Dan Saladino

'A sparklingly intelligent examination of, and a meditation on, the interplay of cooking and identity' Spectator

________

In National Dish, award-winning food writer Anya von Bremzen sets out to investigate the eternal cliché that "we are what we eat". Her journey takes her from Paris to Tokyo, from Seville, Oaxaca and Naples to Istanbul. She probes the decline of France's pot-au-feu in the age of globalisation, the stratospheric rise of ramen, the legend of pizza, the postcolonial paradoxes of Mexico's mole, the community essence of tapas, and the complex legacy of multiculturalism in a meze feast. Finally she returns to her home in Queens, New York, for a bowl of Ukrainian borscht -a dish which has never felt more loaded, or more precious.

As each nation's social and political identity is explored, so too is its palate. Rich in research, colourful? characters and lively wit, National Dish peels back the layers of myth and misunderstanding around world cuisines, reassessing the pivotal role of food in our cultural heritage and identity.

Featuring an epilogue on Ukrainian borscht, recently granted World Heritage status by UNESCO

________

FURTHER PRAISE FOR NATIONAL DISH

'So enlightening – as well as well so much fun to read… Von Bremzen is a superb describer of flavours and textures' Bee Wilson Financial Times

A fast-paced, entertaining travelogue, peppered with compact history lessons that reveal the surprising ways dishes become iconic' New York Times

'Enchanting, fascinating, thought provoking and humorous' Claudia Roden

'A playful, erudite and mouthwatering exploration of ideas around food and identity. With the help of a diverse group of characters and dishes, Anya von Bremzen highlights the intricacies and contradictions of our relationship with what we eat' Fuschia Dunlop

'Anya von Bremzen's new book reads like an engrossing unputdownable novel about the perpetual soup of humanity' Oli Hercules

'An evocative, gorgeously layered exercise in place-making and cultural exploration…'Boston Globe

'Von Bremzen's knowledge is staggering and her writing witty, urgent and personal. I couldn't put it down' Diana Henry

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.6.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Länderküchen | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Schlagworte | Bee Wilson • best food writing • Consider the Fork • dan saladino • Eating to Extinction • Felicity Cloake • food and cultural identity • food and travel writing • food and wine • food writing • fuschia dunlop • James Beard Award • jeremy lee • mastering the art of soviet cooking • Michael Pollan • One More Croissant for the Road • ottelenghi • shark's fin and sichuan pepper • Stephanie Danler • the edible atlas • the omnivore's diet |

| ISBN-10 | 1-911590-89-8 / 1911590898 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-911590-89-7 / 9781911590897 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 672 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich