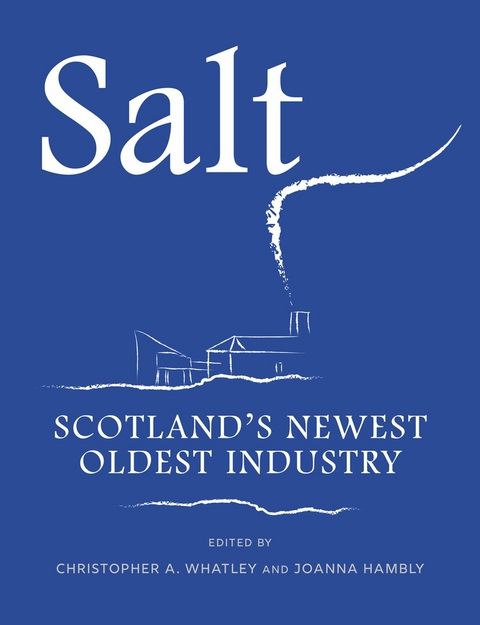

Salt (eBook)

240 Seiten

Birlinn Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78885-590-7 (ISBN)

Joanna Hambly is an archaeologist and research fellow at the University of St Andrews. Through her work with the SCAPE Trust, she manages an award-winning national programme of community research into the archaeology of Scotland's coasts and has a long-standing interest in the archaeology of sea-salt manufacture in the UK.

Salt is a vital commodity. For many centuries it sustained life for Scots as seasoning for a diet dominated by grains (mainly oats), and for preservation of fish and cheese. Sea-salt manufacturing is one of Scotland's oldest industries, dating to the eleventh century if not earlier. Smoke- and steam-emitting panhouses were once a common sight along the country's coastline and are reflected in many of Scotland's placenames. The industry was a high-status activity, with the monarch initially owning salt pans. Salt manufacture was later organised by Scotland's abbeys and then by landowners who had access to the sea and a nearby supply of coal. As salt was an important source of tax revenue for the government, it was often a cause of conflict (and military action) between Scotland and England. The future of the industry and the price of salt for consumers was a major issue during negotiations around the Union of 1707. This book celebrates both the history and the rebirth of the salt industry in Scotland. Although salt manufacturing declined in the nineteenth century and was wound up in the 1950s, in the second decade of the twenty-first century the trade was revived. Scotland's salt is now a high-prestige, green product that is winning awards and attracting interest across the UK.

Christopher A. Whatley OBE FRSE is Professor of Scottish History at the University of Dundee. His publications include the award-winning The Scots and the Union, Immortal Memory: Burns and the Scottish People and Pabay: An Island Odyssey. Joanna Hambly is an archaeologist and research fellow at the University of St Andrews. Through her work with the SCAPE Trust, she manages an award-winning national programme of community research into the archaeology of Scotland's coasts and has a long-standing interest in the archaeology of sea-salt manufacture in the UK.

CHAPTER 2

A Brief History of Scottish Salt from the Eleventh Century to the Late Twentieth Century

Richard Oram and Christopher A. Whatley

The earliest known surviving documentary reference to a salt-making site in Scotland is a frustratingly terse statement found among a series of Latin notitiae of eleventh-century grants made by Scottish kings to the monastic community of Céli Dé, located on St Serf’s Island in Loch Leven. The note records that ‘Malcolmus Rex filius Duncani concessit eis salinagium quod Scotice dicitur Chonnane’ (King Malcolm son of Duncan (Malcolm III) granted to them the saltworks which in Scots (Gaelic) is called ‘Chonnane’).1 It provides us with neither a firm date for when the award was made – although the attribution to King Mael Coluim (r. 1057–93) alone, rather than to both the king and his second wife, St Margaret, points to some time probably in the 1060s – nor where ‘Chonnane’ was located. None of the monastery’s other lands lay near the Firth of Forth, where a saltwork is most likely to have been located, and there is no evidence for its existence in the records of the Augustinian priory cell that replaced the Céli Dé community in the 1150s. All we can say with confidence is that salt production was already established on the south coast of Fife by the third quarter of the eleventh century, but we have no evidence for how long such operations had been functioning before that time. There is a veritable explosion of data for a well-established industry from the second quarter of the twelfth century onwards. This material has been discussed in detail elsewhere and will not be re-examined here beyond some key points.2 Other than a summary of the wider Scottish salt industry, the emphasis in the following section will instead be on a new examination of the evidence for the existence of salt production in the Middle Ages in the land flanking the Moray Firth.

Overview of the Firth of Forth

It is clear that salt production was already being conducted at scale on the shores of the inner reaches of the Firth of Forth west of Inverkeithing, and was probably associated with the by then well-established complex of royal and aristocratic lay estates in the region. Certainly King Mael Coluim’s later eleventh-century grant to St Serf’s was of an already functioning saltworks from his own property portfolio. The household of that king’s youngest son, King David I (r. 1124–53) was in receipt of salt delivered ‘for the king’s use’ at Dunfermline c.1128,3 possibly from the pans at Inverkeithing, whose saltmaster tried to prevent his great-great-grandson King Alexander III (r. 1249–86) from riding on towards Kinghorn in the storm and darkness in March 1286.4 Already by the first half of David I’s reign, however, it is clear from the surviving documentary records that what was probably the main production centre seems to have been located on the estuarine flats of the Forth carselands, downstream east from Stirling on both sides of the river.

Records of saltpans in this area present, at first sight, the appearance of an operation that was dominated by monastic ownership, for much of our surviving record is preserved among the charters that recorded gifts of property made to the great abbeys and priories of east central Scotland from the 1120s onwards. Closer reading of these documents, however, reveals that the monastic saltpans were part of a wider industrial landscape of lay-owned sites. The crown was probably one of the biggest of the lay owners, as illustrated in c.1139, when King David I informed the sheriff of Stirling that he ‘desired that the abbot of Dunfermline have a saltpan beside my pans’ at Stirling.5 Some of those royal pans referred to in the Dunfermline gift might later have been alienated by the king, for between 1140 and 1153 David granted pans to Newbattle Abbey (in Carse of Callendar), Holyrood Abbey (at Airth), Kelso Abbey (in the Carse), Cambuskenneth Abbey (in the Carse of Stirling) and Jedburgh Abbey (‘beside Stirling’).6 David’s grants and subsequent confirmations by his grandsons and successors reveal that the majority of saltpans that were being gifted by the king to monastic proprietors down to the middle of the twelfth century were concentrated on the carselands extending along both sides of the Forth, from Stirling eastwards to Kincardine on the north and what is now Grangemouth on the south. These initial grants became a springboard for later development on a larger scale by the individual monastic owners.

One of the better-recorded examples of this expansion occurred in the district of saltmarsh and estuarine muds extending east from Airth towards the mouth of the River Carron and further east again to the mouth of the Avon. Newbattle and Holyrood were the principal beneficiaries here in a zone that was relatively underdeveloped in the mid twelfth century.7 The salt-saturated muds of these flats were ideal for recovering salt through the sleeching process,8 and first woodland in the Callendar district beside Falkirk and then the extensive raised peat-moss that extended west beyond Airth towards Cowie supplied its fuel. Although Newbattle appears to have feued its interests locally to the canons of Holyrood, the Holyrood operation continued to be operated by its cottar tenants there into the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, when coastal inundation led to a withdrawal from the reclaimed land around the mouth of the Carron.9

Medieval salt making beyond the Forth region

Although the Forth carses seem to have had by far the largest concentration of sites of salt production through sleeching, it was not the only part of the Scottish coast suitable for this kind of salt manufacture. A further 20 sites identified from monastic records, but including lay as well as monastic properties, can be shown to have been in operation before 1200 in areas appropriate for sleeching spread from the inner Solway region between Annanfoot and the Nith estuary in the south-west to the Mearns coast immediately south of Aberdeen in the north-east. In the later twelfth century we have record of Kelso- and Melrose-operated pans at Kirkbean and Rainpatrick on the Solway coast, the latter occurring alongside pans operated by the more important knightly tenants of the Bruce lords of Annandale. Melrose’s pans at Doonfoot in Carrick, St Andrews’ pan at Balgove, Arbroath’s at Dun on the Montrose Basin, alongside pans operated by their benefactor Sir John de Hastings, and Coupar Angus’s at Altens (Nigg Bay), gifted to them by Sir Walter Bisset, were all on expanses of sand or mud-flat or in coastal saltmarshes.10

Lack of substantial documentary records from some of these areas renders it difficult to obtain a sense of the scale of salt-production operations. In the Montrose Basin, the wide expanse of tidal sands that form the estuary of the River South Esk, we know that there were probable sleeching sites attached to royal estates in operation there by at the latest the 1160s, when King Malcolm IV (r. 1153–65) granted a teind of their produce to Restenneth Priory.11 We do not gain any insight from the surviving Restenneth charter or the very fragmentary records of its mother-house at Jedburgh, where the pans at Montrose were located, whether on the Basin proper or on the sandy coastal links that extend north from the burgh to the mouth of the North Esk at Kinnaber. It is clear from the grant to Arbroath of a pan site by John de Hastings c.1206, mentioned above, that it was part of a complex of such operations functioning by that date on the north shore of the Basin within his lordship of Dun, for it was described as ‘iuxta salinas meas’ (next to my saltworks). Similarly, although we have only the reference to the pan operated by the canons of St Andrews at Balgove on the sands south of the mouth of the Eden estuary north-west of the burgh, functioning in the late twelfth century, it is likely that the de Quincy lords of Leuchars were also operating pans of their own on the opposite side of the river-mouth.

Medieval salt making in the Moray Firth region

The majority of the known twelfth- and thirteenth-century salt-production sites lie in these eastern and south-western districts, but it is now certain that other centres were operative from at least the early 1200s in more northerly and westerly locations. What we shall probably never know is whether these were the product of the settlement by colonists from southern Scotland and England after c.1150 in the conquered territory of the rulers of Moray that extended west of the Spey into the firthlands round the head of the Moray Firth, or elements of an older native tradition of salt production. Given the likely demand for salt as a preservative in the salmon-fishing and cattle-owning culture of pre-1150 Moray, it is unlikely that there was no capacity for indigenous production of salt, but no earlier sites are yet known. Least well-known of the early northern sleeching centres is the zone of former brackish lagoons that lay to the east and west of the mouth of the River Lossie in the Laich of Moray.12 The surviving watery expanse is Spynie Loch, a freshwater pond that is all that was left after the drainage of the laich’s main lagoon basin through the early nineteenth-century drainage-channel of the ‘Great Cut’, which formed part of the region’s agricultural...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.9.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Archäologie |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Wirtschaftsgeschichte | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Anthology • archaeologists • archaeology • award-winning • Ayrshire • Blackthorn Salt • business • Chris Whatley • coastal archaeology • contributors • Economic History • Economics • Essays • historians • History • Isle of Skye Salt • Jo Hambly • Local History • new industry • Prestige • Prestonpans • Rebirth • Revival • rich mix • SALT • salt entrepreneurs • salt industry • salt mining • salt pans • Scotland • scottish archaeology • Scottish History • Sea-salt • St Andrews • twenty-first century • vital commodity |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-590-6 / 1788855906 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-590-7 / 9781788855907 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 29,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich