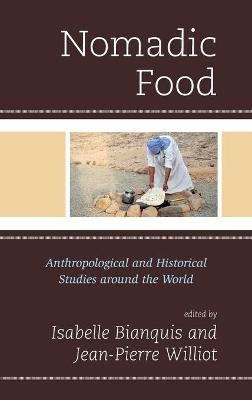

Nomadic Food

Rowman & Littlefield (Verlag)

978-1-5381-1598-5 (ISBN)

Food is unquestionably a total social fact and 'we must now think of it as a social fact that is characteristic of new global lifestyles' (Rasse and Debos, 2006). The structural organization of the market and eating behaviors are undergoing great changes. Strictly speaking, this development is not really new. Every century, every major caesura in the history of humanity could illustrate a process of inventions, adaptations, and innovations which have transformed eating habits. The contemporary period, however, is different because of the extent of these major changes and the global importance of some of them. Thus, organizations such as manufacturers, retailers, and transportation companies are all highly inventive in offering individuals eating solutions which are adapted to their new lifestyles; lifestyles which are based or, at the very least, affected by increased mobility and continuous moving around. Of course, travelers have made journeys throughout history, and they have always had to deal with the issue of how to eat when away from home. Whether associated with long-distance journeys, random travels, or tourist trips, mobility has been an important factor in the creation of catering and eating solutions which range from the very simple to the elaborate. Today, this increased mobility makes us think of practices which have been described as nomadic. However, can a link be found between the nomadism of people who move around in order to find food for their herds or for themselves and the nomadic forms of eating of our mobile societies? The collection of contributions that we are proposing will try to provide answers to this.

The traditional understanding of the concept of nomadism generally refers to pastoral practices which are to be found in many populations such as the Lapps, the peoples of Central Asia,or the Tuaregs. The term 'nomadism' is also used to describe the lives of hunter-gatherers and some sea nomads, such as the Bajau of Indonesia, and the Moken, the Moklen, and the Urak Lawoi of Thailand. It has also been used to refer to gypsies, or Roma, who, since a French law of 1969, have been called 'gens du voyage' (travelers). Although mobility is an invariant in these different types, it is nonetheless true that the term refers to the ways of life lead by organized social groups who are the bearers of a specific identity. However, it is impossible to simply correlate these nomadic practices with the habit of food consumption outside the home or living place since nomads do not have any home other than where they stop on a temporary basis. The concept of nomadism has undergone profound changes in recent decades, taking on a semantic scope that gives it the ability to just as easily include working practices, communication processes, and new forms of social behavior.

In this book, we intend to examine the many meanings of the term 'nomad' through the study of food habits. Food and beverage products have become just as nomadic as other objects, such as telephones and computers, whereas in the past only food and money were able to move about with their carriers. Food industries have seized control of this trend to make it the characteristic feature of consumption outside the home - always faster and more convenient, the just-in-time meal: 'what I want, when I want, where I want', snacks, finger food, and street food. The terms reveal the contemporary modernity and spread of food practices, but they are only modified versions of older and more uncommon forms of behavior. Mobility, in the sense of multiple forms of moving about using public or individual, and possibly intermodal, means of transport, on spatial scales and temporal rhythms which are frequent and recurring but variable, responding to professional or leisure needs, can serve as a basic premise in order to gain insight into the concept of food nomadism.

Have we passed from a group and territorially-defined way of eating to a solitary and mobile, so-called nomadic way of eating? This vision connecting mobility and freedom is a little far-fetched for several reasons. Firstly, the food of the nomads is not nomadic. Within the context of traditional nomadism, people move about but they always eat inside their habitat, which is itself mobile. On the other hand, the ideology of Western modernity goes together with the ideology of movement, which is itself deeply linked to a perception of time. In this approach, space is not only territory, it is also space-time. Sedentary people, whether by choice or time constraints and pendular migrations, have to live, think and eat 'nomad'.

In a multi-author work published in 2002, the authors distinguished two forms of mobility: moving about in order to do one's shopping, and moving about in order to have meals away from one's home. In the first case, they saw a sedentary specificity, whereas in the second they saw a 'nomadic' (in quotation marks) specificity. This latter was linked to a so-called 'semi-nomadic' way of life. Also included in this second category were migrant workers who meet up in public places such as Paris' Sahelian cafés, which were described by one of the contributing authors (Hug). The comparison between the different fieldwork studies presented enabled us to perceive some common features of this food mobility: the idea of saving time, the limitation of social control, and, for young people, experimentation in food inversion strategies. The authors also pointed out that eating outside the domestic space should not be seen as a solitary experience as it takes on a social meaning, according to which one can want to eat with one's peers, avoid having to eat with one's family, and make the most of the opportunity to build up networks. Sociological and anthropological works generally show that eating outside the home is not necessarily synonymous with anomie.

Eating within the context of mobility generates specific terms of supply, portability, preservation and preparation techniques, consumption patterns, e.g. sitting, standing, together, alone, walking, or with one's hands, and the encountering and assimilating of new models, such as the exchange of recipes and techniques, and the discovery of new products. Nomadic food consumption, just like the products which contribute to it, is therefore a powerful source of exchange and discovery, of the widening appeal of new foods and recipes, and of innovation in taste.

Jean-Pierre Williot is Professor of Contemporary History at François-Rabelais University, Tours. Research team: LéA (EA 6294). Fields of specialization: History of food innovation, railways, and the gas industry. Isabelle Bianquis is Professor of Anthropology at François-Rabelais University, Tours. Research team: LéA (EA 6294). Ethnographic areas: Mongolia, Russia, France. Fields of specialization: Socio-cultural anthropology, food studies, alcohol, traditions and transformations.

Introduction

From noun (the food of the nomads) to adjective (nomadic feeding), (Isabelle Bianquis)

1-The food of the nomads

Sandrine Ruhlmann, The bowl and the spoon: the culinary objects of nomads in Mongolia

Nir Avieli, McDonald's in Beersheba: Israeli Bedouins in the global oasis

Salamatou Sow, Aspects of food in the nomadic Fulani group of Niger

2-Eating and mobility

Stefano Magagnoli, Italian-sounding food: a global cuisine carrier that travels well

Pierre Antoine Dessaux, Defining and implementing the field ration: a comparative study in food cultures, science, and mobility patterns

Jean Baptiste Schneider, The nutrition of European migrants aboard transatlantic ships during the first half of the 19th century

Marc de Ferrière le Vayer, Eating on planes

Philippe Pesteil, Eating on the hiking trails in Corsica: between hi-tech and tradition

Jaroslaw Dumanowki, Vinegar powder: Polish travelers’ food in early modern times

Chantal Crenn, The circulation of food practices and representations among Senegalese retirees in Bordeaux and Dakar: the effects of migration and reverse migration

3-The imaginary

Jane Duruz, Culinary nomadism at the Addis Ababa Café: intimate exchanges shaped by global mixed race, diasporic belongings, and cosmopolitan sensibilities

Luciano Maffi, The traveling priest: food for the spirit and food for the body

Isabella Borissova, Nomadic food in Yakutia

Gallina Kabakova, The nourishing and protecting snack: the Russian case (late 19th - early 21st centuries)

Chiemi Okumoto, Ekiben - train station bentos in Japan: towards a better appreciation of space and time in nomadic foodways

Conclusion: The transition from the food of nomads to nomadic food (Jean-Pierre Williot)

| Erscheinungsdatum | 06.11.2019 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy |

| Verlagsort | Lanham, MD |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Maße | 161 x 206 mm |

| Gewicht | 553 g |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Technik ► Lebensmitteltechnologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5381-1598-0 / 1538115980 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5381-1598-5 / 9781538115985 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

aus dem Bereich