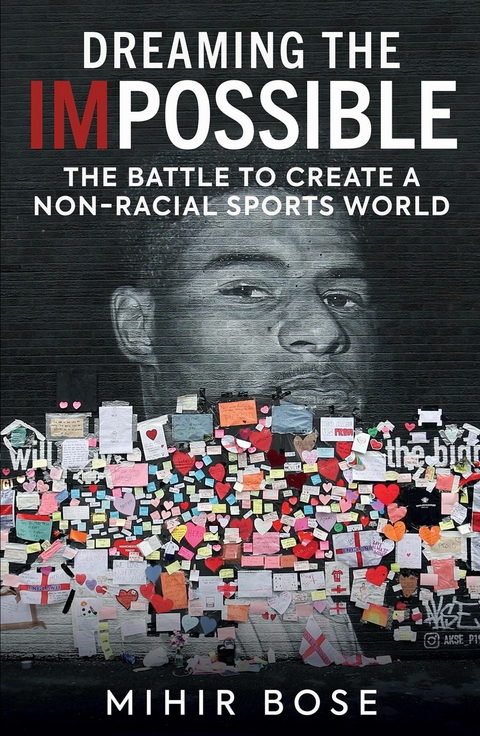

Dreaming the Impossible (eBook)

352 Seiten

Arena Sport (Verlag)

978-1-78885-534-1 (ISBN)

The British, who are rightly proud of their sporting traditions, are now having to come to terms with the dark, unacknowledged, past of racism in sport – until now the truth that dare not speak its name.

Conscious and unconscious racism have for decades blighted the lives of talented black and Asian sportsmen and women, preventing them from fulfilling their potential. In Formula One, despite Lewis Hamilton's stellar achievements, barely one per cent of the 40,000 people employed in the sport are of ethnic minority heritage. In football, Britain's premier sport, the number of non-white managers in the professional game remains pitifully small. And in cricket, Azeem Rafiq's testimony to the Commons select committee has exposed the scandal of prejudice faced by Asian cricketers in the game.

Veteran author and journalist Mihir Bose examines the way racism has affected black and Asian sportsmen and women and how attitudes have evolved over the past fifty years. He looks in depth at the controversies that have beset sport at all levels: from grassroots to international competitions and how the 'Black Lives Matter' movement has had a seismic impact throughout sport, with black sports personalities leading the fight against racism. However, this has also led to a worrying white fatigue.

Talking to people from playing field to boardroom and the media world, he illustrates the complexities and striking contrasts in attitudes towards race. We hear the voices of players, coaches and administrators as Mihir Bose explores the question of how the dream of a truly non-racial sports world can become a reality.

The Marcus Rashford mural featured on the cover was commissioned by the Withington Walls community art project, created by artist AskeP19 (@akse_p19) and based on photography by Danny Cheetham (@dannycheetham). To find out more about the Withington Walls project, you can follow them at @Withingtonwalls on both Twitter and Instagram, or visit their website: www.withingtonwalls.co.uk

Mihir Bose is a British-Indian journalist and author who was the first Sports Editor of the BBC. In nearly 50 years in journalism he has worked for the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph and written on sport, business and social and historical issues for the Financial Times, Daily Mail, Independent, Sunday People, Evening Standard, Irish Times and History Today and broadcast for Sky, ITV, Channel Four News and was the first cricket correspondent of LBC Radio. He is the author of 37 books. His History of Indian Cricket won the 1990 Cricket Society Silver Jubilee Literary Award. His Sporting Colours was runner-up in the 1994 William Hill Sports Book of the Year.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.5.2022 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 12pp colour plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Schulbuch / Wörterbuch ► Lexikon / Chroniken | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Hilfswissenschaften | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Makrosoziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Azeem Rafiq • #blacklivesmatter • Black lives matter • BlackLivesMatter • books on british sport • Boris Becker • Britain • British sport • challenging • Chris Froome • community art • Cricket • Crystal Palace • Diversity • EDI • eqaulity • fascinating • Football • football racism • Hamza Abdullah • History of sport • inclusivity • Institutional Racism • lionesses • Majid Haq • Mako Vunipola • Marcus Rashford • Marion Bartoli • Mural • Premier League Racism • Racism • racism in sport • Raheem Sterling • Roy Hodgson • shortlisted • Show Racism the Red Card • Soccer • Sport • sport books • Sports Book Awards • steph houghton • Sunday Times • Tennis • Thought-provoking • Withington Walls |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-534-5 / 1788855345 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-534-1 / 9781788855341 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich