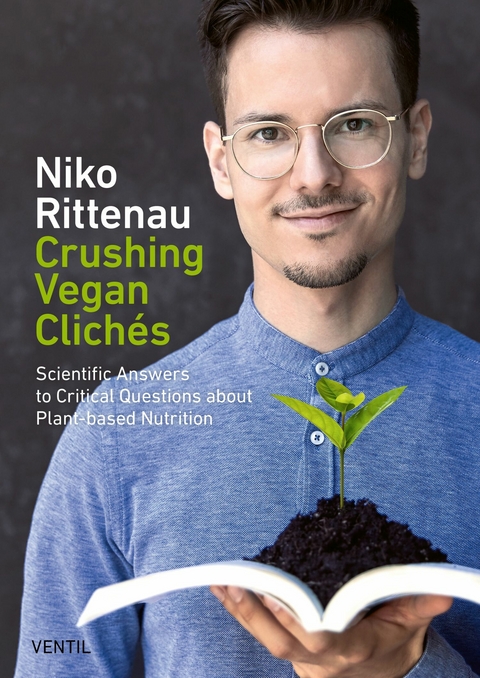

Crushing Vegan Clichés (eBook)

424 Seiten

Ventil Verlag

978-3-95575-638-3 (ISBN)

Berlin-based Niko Rittenau is a nutrition expert focused on plant-based nutrition. He combines his culinary skills and solid knowledge of nutri- tional science from his academic studies to innovate and inspire, bringing together great taste, health awareness, and sustainability. In lectures and seminars he illuminates his vision of responsible dietary choices with a focus on wholesome foods to appropriately nourish a rapidly-growing world population. Niko has a bachelor's degree in Nutritional Sciences and a master's degree in Micronutrient Therapy and Holistic Medicine.

Berlin-based Niko Rittenau is a nutrition expert focused on plant-based nutrition. He combines his culinary skills and solid knowledge of nutri- tional science from his academic studies to innovate and inspire, bringing together great taste, health awareness, and sustainability. In lectures and seminars he illuminates his vision of responsible dietary choices with a focus on wholesome foods to appropriately nourish a rapidly-growing world population. Niko has a bachelor's degree in Nutritional Sciences and a master's degree in Micronutrient Therapy and Holistic Medicine.

Although dozens of vegan athletes around the world are breaking records in a variety of sports, some publications still mistakenly associate vegan diets with decreased strength, endurance, and performance as well as insufficient protein. However, successful athletes have proven that even after years of following entirely plant-based diets, physical strength isn’t compromised. Vegan strongman Patrik Baboumian, as an excellent example, set the world record in 2013 for the Yoke Walk by carrying 555 kg for over ten meters.1 There’s also Ultramarathon runner Scott Jurek, who has followed a vegan diet since 1999. Jurek has broken many records, including winning the Western States Endurance Run (160 km) seven times in a row.2

Obviously these isolated examples are not evidence-based proof of the benefits of a vegan diet, but they definitely add another dimension to discussions within scientific literature regarding protein requirements of vegan athletes. Hundreds of other athletes also demonstrate that it works not only in theory, but also in practice. Since the DGE lists protein as a critical nutrient for vegan diets,3 we’ll explore in detail how a vegan diet can provide adequate, quality protein. We’ll also see in which circumstances an entirely plant-based diet could indeed be deficient in protein.

The basics of protein

The word protein comes from the Greek word proteios which means “first” or “primary”. The origin and naming of the word gives us insight into how nutritional science has viewed protein since its discovery. The most important function of protein is building tissue in the body, but it’s also used by the body for many other tasks. Dietary protein in the human body is made of about twenty amino acids, only eight of which cannot be made by the body itself. These eight amino acids are therefore “essential” (to survival) and must come from dietary sources.4 There are a few other amino acids that in certain circumstances are essential and are therefore termed “conditionally essential” or “semi-essential”. The amino acid histidine, for example, is listed as a ninth essential amino acid in some publications and only as semi-essential in others. It’s not essential for adults, but is for infants. All of the other twenty relevant amino acids are not essential as they can be made by the body, provided that all materials needed are supplied by the diet. Ultimately, it’s actually not protein itself which is important to the body, but just certain amino acids.5 Since these are generally consumed as dietary protein and not in isolated form, we’ll be talking about protein requirements.

The eight essential amino acids are phenylalanine, isoleucine, lysine, valine, methionine, leucine, threonine, and tryptophan. In order to ensure an adequate supply of all of these amino acids, there are officially established recommended intakes for each. However, the suggestions in this chapter for meeting dietary protein requirements with the right plant foods will allow us to focus on overall protein intake without needing to concern with individual, separate recommended intakes.

Determining protein requirements

According to the DGE, the official recommended daily intake of protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of ideal body weight.6 This agrees with the recommendations of many other dietary and health organizations, including that of the World Health Organization (WHO), which suggests a daily intake of 0.83 grams of well-digestible protein per kilogram of body weight.7 Overweight individuals should calculate their daily protein requirements based on their ideal, healthy body weight, not their actual weight, in order to avoid overestimating protein requirements. Ideal weight is determined with a variety of methods including the Broca index or Hamwi formula, or by using standardized gender-specific charts.8 The official recommendation of 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight has a safety margin calculated into it to account for individual variations. Accordingly, these values should be accepted as optimal intakes rather than absolute minimums. The actual necessary daily amount of protein according to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is only 0.66 grams per kilogram of body weight, given that the protein consumed is well-digestible and of high-quality.9

Based on the DGE’s recommended 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, a healthy 60 kg woman’s daily protein intake would be 48 grams. Using an average caloric value of 4.1 calories (kcal) for each gram of protein, this corresponds to a daily intake of about 197 calories (kcal) from protein per day. With average energy requirements of about 1800 to 2100 calories (kcal) per day10 (depending on activity levels), this is about 10 % of total food energy (e. g. calories). As we’ll discuss in detail later, several sources recommend a slightly higher daily protein intake of 0.9 grams per kilogram of ideal body weight for exclusively plant-based diets. We’ll use this value moving on.

Athletes have increased protein intake requirements, but also need more calories in total. A higher caloric intake is matched by a sufficiently higher protein intake corresponding to the Protein-Energy Ratio, the percentage of calories from protein in relation to total calories consumed. This is enough as long as the ratio is 10 % or more, even with lesser quality protein sources.11

Do vegans get enough protein?

The answer to the question if an exclusively plant-based diet can satisfy the protein requirements of the body was provided in a publication by American nutrition expert Dr. David Mark Hegsted in 1946.12 He emphasized that that a grain-oriented, entirely vegan diet of sufficient calories can meet protein intake requirements. The report relies on the result of a study including 26 participants on a completely vegan diet which were able to achieve a positive nitrogen balance with a protein intake of 0.5 grams per kilogram of body weight. A positive nitrogen balance is a relevant factor in determining if an individual is getting adequate protein. The scientists Dr. Vernon Young and Dr. Peter Pellett also confirmed the ability to meet protein requirements on a vegan diet in a study published in 1994 on the role of protein in nutrition. This publication also showed that on a well-balanced completely plant-based diet with sufficient caloric intake a shortage of protein is not a concern.13 Additionally, both were already aware that relying on conventional animal experiments with rats to attempt to assess protein quality runs the risk of potentially underestimating the role of plant protein in human diets. Early experiments were usually conducted by feeding rodents different types of protein and observing their growth to draw conclusions about the quality of the protein. However, protein from plants often has less of the amino acids that meet requirements for rats, which are higher than for humans. As a result, feeding trials with rats can underestimate the value of plant protein sources for humans.14 At the conclusion of their paper, the authors provide a concise listing of common myths about protein and determine if the statements are grounded in reality. Inspired by this approach, I’ll also list and address the most common myths related to each topic at the end of each chapter of this book.

A number of studies from Great Britain15, Sweden16, Germany17, Switzerland18, and the USA19 likewise reinforce that vegans typically obtain more than 10 % of their calories from protein, thus satisfying official daily protein intakes if their caloric requirements are met. The ground-breaking position paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), formerly the American Dietetic Association (ADA), first published in 2003, officially acknowledged that an appropriately planned diet can ensure adequate protein at any stage of the life cycle.20 This paper was updated in 2009,21 and again in 2016,22 continuing its endorsement a vegan diet for anyone, any type of athletic activity, at any stage of life. Other health organizations, such as the British Dietetic Association (BDA), are also confident a well-planned vegan diet can supply adequate protein for all life stages.23 The statement of the Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA) on the subject of plant-based diets doesn’t even mention protein deficiency, instead emphasizing the importance of getting enough iron, calcium, vitamin B12, and omega-3 fatty acids.24

The American Heart Association (AHA) also assures us that it’s not necessary for anyone to eat animal products to meet their nutritional needs, and that plant protein provides adequate essential amino acids on a well-rounded diet with enough calories.25

Plant-based protein sources

It’s easy to check and see for yourself if you’re getting enough protein to meet daily requirements. With an online nutrition calculator or calorie tracking app, such as Cronometer (www.cronometer.com) just enter the amounts of your choice of legumes, whole...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Mainz |

| Sprache | deutsch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Ernährung / Diät / Fasten |

| Schlagworte | Calcium • Clichés • food pyramid • Fruit • Health organization • iodine • iron • Legumes • Melanie Joy • Nutrition • nutritional circle • Nuts and seeds • Omega-3 fatty acids • plant-based • Protein • Riboflavin • selenium • soy • Vegan • vegan diets • vegetables • Vitamin B12 • Vitamin B2 • Vitamin D • vitamin supplements • whole grains • zinc |

| ISBN-10 | 3-95575-638-6 / 3955756386 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-95575-638-3 / 9783955756383 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 70,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich