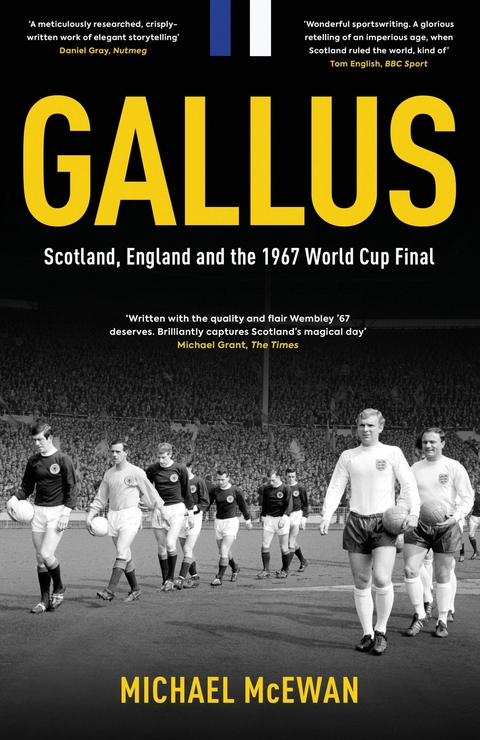

Gallus (eBook)

368 Seiten

Polaris (Verlag)

978-1-913538-98-9 (ISBN)

Michael McEwan is a journalist from Glasgow. He is the Assistant Editor of PSP Media Group's portfolio of sports titles, which include Bunkered, Scotland's highest circulating golf magazine. He is a former winner of both the RBS Young Sportswriter of the Year and Evening Times Young Football Journalist of the Year awards and the author of Running the Smoke: 26 First-Hand Accounts of Running the London Marathon.

There are two kinds of people in this world. Those who insist that football is just a game, and those who know better. Take the April 1967 clash between England and Scotland. Wounded by their biggest rivals winning the World Cup just nine months earlier, Bobby Brown's Scots travelled to Wembley on the mother of all missions. Win and they would take a huge step towards qualifying for the 1968 European Championship, end England's formidable 19-game unbeaten streak, and, best of all, put Sir Alf Ramsey's men firmly back in their box. Lose? Well, that was just unthinkable. Meanwhile, off the pitch, the winds of change were billowing through Scotland. Nationalism, long confined to the margins of British politics, was starting to penetrate the mainstream, gaining both traction and influence. Was England's World Cup victory a defining moment in the Scottish independence movement? Or did it consign Scotland to successive generations of myopic underachievement? Michael McEwan, author of The Ghosts of Cathkin Park, returns to 1967 to explore a crucial ninety minutes in the rebirth of a nation.

Michael McEwan is a journalist from Glasgow. He is the Assistant Editor of PSP Media Group's portfolio of sports titles, which include Bunkered, Scotland's highest circulating golf magazine. He is a former winner of both the RBS Young Sportswriter of the Year and Evening Times Young Football Journalist of the Year awards and the author of Running the Smoke: 26 First-Hand Accounts of Running the London Marathon.

PROLOGUE

AS THE RAIN HAMMERED AGAINST THE WINDOW, Britain’s most expensive footballer picked up his phone and dialled the number. It was a little after 10 a.m. on the morning of 30 July 1966 and Denis Law wanted revenge. Distraction, too. But mainly revenge.

A few weeks earlier, one of the Manchester United forward’s best friends, a local businessman called John Hogan, had beaten Law over eighteen holes at a local golf course. This, despite the fact that Law was the better player of the two (and by some distance).

Oh, how Hogan had revelled in what was a rare win over his old pal. ‘Any time you want a return game,’ he had crowed, ‘just give me a shout.’

The words rang in Law’s ears as Hogan answered.

‘Remember how you said “a return match any day, you name it,’’’ Law reminded him. ‘Well, I will name it now – today.’

Hogan was as incredulous as he was crestfallen, and it had nothing to do with being a fair-weather player.

‘But Denis . . . today’s the World Cup final.’

Not just any old World Cup final but the first World Cup final to feature England. A 2–1 win over a Eusébio-led Portugal in the semi-finals had earned the Three Lions a shot at the title, and on home soil, too. Ninety minutes. Ninety measly minutes were all that stood between Alf Ramsey’s men and the right to hear their names echo in sporting perpetuity. The country had ground to a halt, intoxicated by an irresistible cocktail of anticipation and expectation. Shops closed early, alternative plans were cancelled, street parties were convened, and Hogan had been looking forward to joining in the fun.

Law had other ideas. A £25 wager managed to persuade Hogan and, in short order, a tee time at Chorlton-cum-Hardy Golf Club, just a few miles to the south of Manchester city centre, was booked.

Law was grateful for the diversion. Two years earlier, he had received the Ballon d’Or, the gilded trophy awarded to Europe’s ‘Footballer of the Year’. He was the first Scot and only the second Brit – following the great Stanley Matthews in 1956 – to land the prestigious honour.

Since then, though, his form and fortunes had taken a dip. The season just ended had finished in abject disappointment on all fronts for Law and his United teammates. Partizan Belgrade had beaten them 2–1 on aggregate in the semi-finals of the European Cup. Three days later, Everton denied them a place in the FA Cup final, a late goal from Colin Harvey settling a scrappy contest at Bolton’s Burnden Park. Their league title defence finished on a note every bit as meek. Having won the old First Division for a sixth time twelve months earlier, the ‘Red Devils’ could do no better than fourth in 1965/66. Worse, they had to watch as fierce rivals Liverpool took the title – for a record seventh time. All of which is to say nothing of United’s other major adversary, Manchester City, winning the Second Division to seal promotion back to the top flight after a three-year absence.

And yet that wasn’t even the worst of it. At the end of the season, Law found himself transfer-listed by the Old Trafford club after asking for a pay rise. In a letter to manager Matt Busby, he outlined his desire for an extra £10 per week, explaining that he would look for a transfer if his demands weren’t met. Busby, a shrewd operator, was less than impressed with his fellow Scot. ‘Law has issued an ultimatum by letter that unless he receives certain terms and conditions, he wants a transfer,’ he told the press. ‘The club is certainly not prepared to consider it and has decided to put him on the transfer list.’

The news caught up with Law on a golf course in Aberdeen. He was in his hometown awaiting the birth of his second child when a reporter from the local Evening Express newspaper found him on the links and relayed Busby’s bombshell.

The frenzied reaction forced Law to go into hiding for a couple of days to, as he would later put it, ‘avoid the glare of publicity’ but before the week was out, he flew to Manchester for showdown talks with the boss. It took them around an hour to thrash it all out. Busby privately agreed to Law’s terms and took him off the transfer list. In return, he wanted to make an example of his star man, lest anyone else in the squad suddenly start feeling brave about his own situation. Busby opened a drawer and pulled out a pre-prepared written apology that was almost ready to be shared with the press and the public. All it needed was Law’s signature. Busby handed him a pen and his comeuppance.

It was a humiliating end to a miserable year in which Law had nursed a bothersome knee injury that restricted him to only fifteen goals in thirty-five league appearances.

So, sit at home and watch England play in the World Cup final, potentially even win the bloody thing? Not today, thank you very much. The thought alone made Law’s insides boil. It would be much more fun, he decided, to put Hogan back in his box.

At least, that was the plan.

* * *

AROUND THE SAME TIME, in the Hendon House Hotel in North London, Law’s Manchester United teammate Nobby Stiles was making a phone call of his own. His need was different but no less urgent.

The night before, England boss Alf Ramsey had taken Stiles and his teammates to the cinema to see Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, a film about an air race set in 1910. Stiles, though, had accidentally left a cardigan behind and he wanted – no, needed – to get it back. This wasn’t just any cardigan. It was his lucky cardigan. He had worn it before every big game he had ever played, and it had never let him down. The prospect of going into the World Cup final without it was precisely the kind of cosmic drama the twenty-two-year-old didn’t need.

After what seemed like an eternity, somebody at the Hendon Odeon finally answered Stiles’ desperate call. He waited as the person on the other end of the line rummaged through the lost property, but to no avail. Nothing had been handed in. Superstitious Stiles would need to tackle this one without his beloved knitwear.

Elsewhere in the same hotel, another Manchester United star was sizing up wardrobe issues of his own. Bobby Charlton had become accustomed to big games and occasions since making his debut for Matt Busby’s Red Devils a decade earlier. League deciders, FA Cup finals, the latter stages of European competition – you name it, Charlton had first-hand experience of it all. Well, nearly all. The World Cup final was new territory for the twenty-nine-year-old. A notoriously early riser, he found himself pacing the room he shared with Everton left-back Ray Wilson and that just wouldn’t do. He needed to do something to distract him from the date with destiny he had lined up at 3 p.m. that afternoon.

He convinced Wilson to join him in getting out of the team’s hotel HQ for a short while. A couple of days earlier, Charlton had bought a new shirt from a local shop but, on reflection, it wasn’t really to his liking and so, hours before the biggest game in the history of English football, he decided to return it.

Off the pair went, down Parson Street and into Hendon town centre, forcing stunned onlookers into a succession of double-takes. Some stopped to wish them luck. Most, though, left them to go about their business, perhaps sensing that this was the players’ way of normalising a most abnormal day.

After around an hour, they returned to the hotel where their teammate, Fulham full-back George Cohen, was reading – and, at Ramsey’s insistence, replying to – some of the fan mail that had been steadily piling up.

It had been a broadly successful shopping trip. Charlton had managed to get his shirt changed and had also bought some cufflinks, a gift for his friend José Augusto, the tricky Portuguese winger, whom he would see at a banquet hosted by FIFA that night. More importantly, the trip had helped kill time.

It was just after 1 p.m. when Charlton and his teammates boarded the team bus and set off for Wembley. A police motorcycle escort accompanied them on their way as fans banged on the sides of the coach and roared their encouragement. As they passed the Hendon Fire Station, the freshly polished bells rang out in support.

This was Charlton’s third World Cup. His first, in Sweden in 1958, had ended in heartache when the Soviet Union defeated England in a playoff to advance to the knockout stages. In Chile four years later, he scored in a 3–1 group stage win over Argentina as England made it to the quarter-finals only to lose 3–1 at the hands of eventual winners, Brazil. This, though, was different. The quiet groundswell of optimism that had been building behind Ramsey’s men in the months leading up to it had gathered momentum as the tournament had worn on. A goalless draw in the opening match with Uruguay had been followed by back-to-back 2–0 wins over Mexico and France as England breezed through the group stages. A bad-tempered quarter-final with Argentina was settled by a late Geoff Hurst goal, which set up a semi-final with inspired debutants Portugal. Charlton bagged a double only for a late Eusébio penalty to set up a tense finish. Portugal, who would finish the tournament as top scorers, threw everything they could at Gordon Banks’ goal as they searched for an...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.9.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 16pp colour plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sport ► Ballsport ► Fußball |

| Schlagworte | 1967 • alf ramsey • April • Bobby Brown • Cathkin Park • England • European Championship • Football • Football History • Ghosts of Cathkin Park • Nationalism • Politics • rivalry • rivals • Scotland • Soccer • The Grudge • Tom English • Wembley • World Cup |

| ISBN-10 | 1-913538-98-2 / 1913538982 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-913538-98-9 / 9781913538989 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich