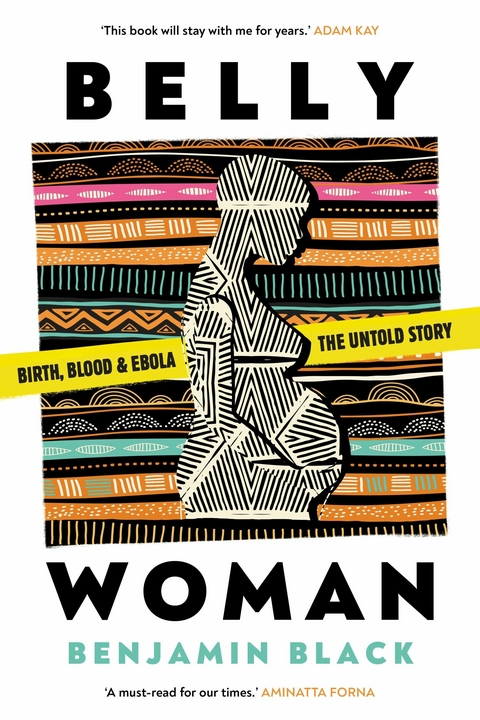

Belly Woman (eBook)

368 Seiten

Neem Tree Press (Verlag)

978-1-911107-58-3 (ISBN)

Dr Benjamin Black is a descendent of Iranian, Jewish, and British roots. His family heritage of persecution and forced migration led him to a career in medical humanitarian relief. He is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist based in London and a specialist advisor to international aid organisations, including Médecins Sans Frontières, government departments, academic institutions, and UN bodies. Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic he provided frontline healthcare to pregnant women and supported the development of international guidelines. Benjamin teaches medical teams around the world on improving sexual and reproductive health care to the most vulnerable people in the most challenging of environments.

Dr Benjamin Black is a descendent of Iranian, Jewish, and British roots. His family heritage of persecution and forced migration led him to a career in medical humanitarian relief. He is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist based in London and a specialist advisor to international aid organisations, including Médecins Sans Frontières, government departments, academic institutions, and UN bodies. Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic he provided frontline healthcare to pregnant women and supported the development of international guidelines. Benjamin teaches medical teams around the world on improving sexual and reproductive health care to the most vulnerable people in the most challenging of environments.

2: PRE-DEPARTURE PLANNING

CAMDEN, LONDON

MONDAY, 16 JUNE 2014, 7.30 A.M.

I am on the floor, sitting on top of a bag I have spent weeks deliberating over. I try to squeeze another book inside the rucksack. No matter how I manoeuvre myself, or the zip, it won’t close. My parents look at the room; clothes and belongings are sprawled across the floor, with me in the middle.

‘Have you packed some snacks, for when you arrive?’ asks Mum, trying to sound relaxed.

I glance up from my position on the bulging bag. My face says it all: Do. Not. Talk. To. Me. They retreat.

My parents had travelled down from their home in Manchester to bid me farewell. I’m thirty-two years old, a doctor, their youngest child and only son, pausing my career, and all our lives, to pursue my ambitions in the humanitarian sector.

Soon, I will begin a journey to Brussels for briefings from MSF’s Operational Centre (OC). From there, I will continue to Sierra Leone. MSF has hundreds of projects, working in over seventy countries, providing emergency and medical assistance. I had spent days reading their reports, (self-critical and reflective); and evenings reading the testimonies of their field workers, (emotive and exhilarating). I wanted to be a part of their independent, humanitarian, medical identity, getting to the places where aid was needed most.

MSF has a complicated organizational structure. It is split into five separate sections, each with its own culture and operational priorities; they are, however, united under a single manifesto and logo. The sections are named after the cities where their headquarters reside: Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Geneva and Barcelona. The Operational Centre of Brussels, or OCB, had been present in Sierra Leone for many years, and their maternal and child health hospital was a jewel in their crown, both in terms of size and the numbers of patients treated.

The project was called the Gondama Referral Centre, or GRC. It was located close to Bo city, the largest city after the capital, Freetown. I was aware of the project, as it was a well-known destination for obstetricians working with MSF.

I had sat in a stuffy London pub on Great Portland Street with another obstetric doctor, Pip, who had spent two years out in the field with MSF, six months of which were in GRC. ‘You’ll be fine,’ she’d told me, as she recalled massive haemorrhages, tropical infections and near-death experiences.

In the months before I was sent to GRC, a strategic decision had been made at the Brussels headquarters for it to stop providing maternity care. Child healthcare was to continue, and their interest in Lassa fever, an endemic viral haemorrhagic fever in the area, was increasing, but maternity would end in June 2014.

In May, the World Health Organization (WHO) had released an updated report on global trends in maternal mortality. Sierra Leone had the highest ratio of women dying to live births in the world. According to MSF’s own calculations, GRC had resulted in an over 60 per cent decrease in women dying from childbirth locally and was providing around a fifth of all caesarean sections in the country. Women from a geographical area spanning over a third of the country travelled there for life-saving interventions and surgery. This project was important. But, at some strategic level, maternal health was not important enough.

Internal organizational pressure led to a swift U-turn and a decision at the eleventh hour to continue obstetric services, though the longer-term future of the facility remained uncertain. Suddenly, a service that had been facing imminent closure had openings for obstetricians which needed filling fast. I was called and asked if I could be there within two weeks.

I had built my ambitions on the stories and experiences of civil wars, earthquakes and refugee migrations. I wondered if I was selling out by going to a stable development setting, rather than a fragile humanitarian crisis. An awareness was rising up inside me, though there was a lot of talk of ensuring that reproductive health, including access to emergency obstetric care, was available in every humanitarian response, but the reality was very different. Rather than being prioritized, it was often substituted with proxy activities, leaving limited demand for an obstetrician.

Through medical school, I had studied with the intention of becoming an aid worker, considering specialties with this in mind. A decade earlier, I spent several months working with refugees and migrants crossing from Myanmar into Thailand. The maternal health needs were striking. Women came to us with late complications, or needing a safe place to give birth. Sometimes they arrived after delivering in the jungle, with horribly infected babies. Every day, women would attend with complications of backstreet abortions; without access to contraception or legal abortions, they turned to any willing provider. Dire poverty left many with little choice. Sex was an industry, a way to procure goods, to survive, to feed children or keep a job in a saturated labour market. Women, often girls, arrived bleeding, infected and internally damaged. Despite all the harm to the woman, the botched abortion could be distressingly unsuccessful; often the pregnancy continued unaffected. It was here, as a twenty-three-year-old student, that I concluded obstetrics and gynaecology was my path into humanitarian assistance. The needs were vast, and I was drawn to the deeper questions of how to respond beyond medicines and surgery. The specialty offered everything: it was broad enough to keep me well informed on general medicine, while specialized enough to be of value to a population in crisis.

I took further studies and read book after book on how development and aid agencies had entered into situations with good intentions, but poor outcomes. I learnt about the history, evolution and errors of major aid organizations and how their past shaped their work today. Rather than deterring me, this information made me even more curious. How could we keep getting it wrong? Lessons identified were often called ‘lessons learnt’, but, as I continued to read, this seemed less convincing. My desire to be part of the humanitarian system grew, as my questions of its effectiveness flourished alongside.

Towards the end of March 2014, Ebola virus was confirmed in Guinea.* MSF had assisted in the initial suspicions and identification of the disease. The virus had taken an unusual and concerning course, entering urban areas and crossing international borders – first into Liberia in April, and then Sierra Leone in late May. I had been following the story, but held no desire to be involved in the Ebola response. I was unfamiliar with the disease, and did not see how it could relate to my role.

The week before I was due to leave, I spoke on the phone to Severine, the obstetrics and gynaecology adviser for MSF-OCB. She was out in GRC at the time, and she reassured me that there had been no Ebola cases in the area of the project, the outbreak remaining contained in the east, around the Guinean border. The general consensus was that Lassa fever was of much greater concern, in terms of exposure and risk. I left for Sierra Leone knowing Ebola was there, but without any genuine anticipation that I would encounter it. In retrospect, it seems ridiculous; the epidemic, as we know now, was unprecedented. But, in early June, we had a dragon under our feet only just beginning to awaken; the ferocity and fire were yet to come.

Standing outside the MSF Operational Centre of Brussels, I felt like I was about to enter a special society. Through those doors, huge decisions were made on access to life-saving interventions, often with uncertain consequences. I was about to walk into one of my textbooks, words and thoughts lifting off the page to become people and discussions in meeting rooms. This was the inner sanctum of one of the most recognized non-governmental organizations in the world, a searchlight shining out to me through a haze of humanitarian scepticism.

People rushed around, smiling, chatting, shaking hands. A dynamism filled the air; the energy was a vibrant, and firm: ‘Let’s get the job done.’ In a moment, I had moved from outsider to insider. I wanted to get the job done too.

As the administrative team sorted out my visa applications, a woman around my age came and joined me at the desk. Alice was also heading to Sierra Leone; she was flying out as part of the first MSF Ebola response team in the country. I was impressed by her calmness. There was no shred of fear on her face, just a concern about whether she could fit all the dolls and teddy bears in her bag for the children she would work with. Alice was Danish, a psychologist, and her role was to provide psychosocial support to survivors and families affected by the outbreak.

‘I’m an obstetric doctor, heading out to GRC,’ I told her.

She squinted her eyes. ‘So you’re a very important person then.’

I thought it was a strange comment from a woman who was about to head into an Ebola outbreak. I shrugged, ‘We’re all important people’.

Making my way around the office, each person I met gave me more papers to read, documents to sign and encouragement that I was joining a great project.

Severine, the obstetrics and gynaecology adviser, had travelled into Brussels especially to see me before my departure. We sat together at a long desk, the walls on either side decorated with large maps and magazine-style pictures of refugee camps, MSF operating theatres and striking faces staring into the...

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich