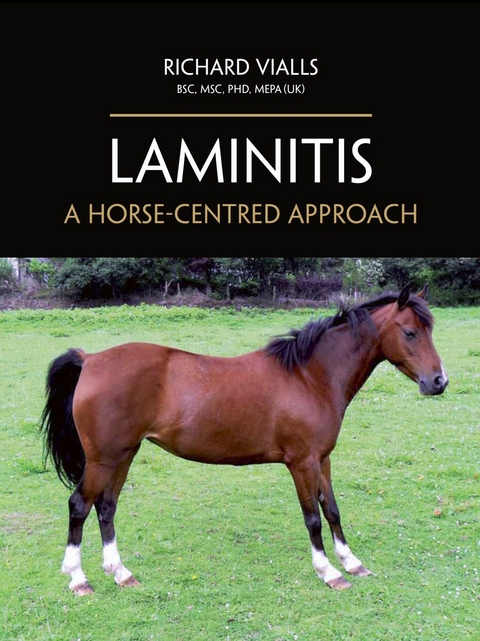

Laminitis (eBook)

208 Seiten

Crowood (Verlag)

978-1-908809-87-2 (ISBN)

Richard Vialls originally trained as a physicist and an electronic engineer and worked for a number of years in the silicon chip industry. His scientific curiosity got the better of him in 2002 after one of his horses went lame and neither vets nor farriers could offer a solution. After training in equine podiatry with a US-based farrier, he began working professionally as an equine podiatrist in 2005. His practice is heavily biased towards remedial cases, with a particular emphasis on laminitis. He is a founder member of the Equine Podiatry Association and has been heavily involved in furthering standards and regulation within the UK equine podiatry profession. He co-founded the Diploma in Equine Podiatry course and has research interests in the clinical presentation of low-grade laminitis, the biomechanics of rotational laminitis and the links between nutrition, digestion and metabolic disease in horses.

2The Established View of Laminitis

This chapter describes the established view of what happens in the equine foot as a result of laminitis, and how to recognize it. The causes of laminitis will be covered in later chapters.

RECOGNITION OF LAMINITIS

Laminitis is defined as inflammation of the laminar corium. It is typically associated with a loss of circulation to the foot. The inflammation (and hence any loss of circulation) tends to be strongest in the toe area. This can be clearly demonstrated by taking a venogram (an x-ray of the foot taken after a dye that blocks the x-rays is injected into a vein, hence making the veins of the foot visible).

Raised Pulses

The heart creates a pressure wave with each beat, which propels blood through the arterial system. As this pressure wave passes through arteries, the artery walls bulge very slightly, and this is what we feel when taking a pulse. If the arterial pressure wave hits a blockage, such as a foot where the blood vessels have closed down due to laminitis, the wave is reflected back, causing pressure to build up locally and the artery to expand more than usual. This can be felt as a stronger than normal pulse. This is an extremely useful diagnostic technique that is used by professionals dealing with laminitis cases, but which can also be used by owners to pick up the early warning signs of a laminitis attack. It is important to note that the pulse rate is not important here (although a faster pulse rate can indicate distress, often combined with rapid breathing): rather it is the strength of the pulse that indicates the severity of the problem.

Fig. 19 Two venograms. LEFT: A healthy foot with the contrast dye filling all the veins. RIGHT: A laminitic foot with loss of circulation in the toe area. Note the lack of contrast dye (and hence the lack of circulation) in the veins at the coronary band and under the tip of the pedal bone, as well as the poor circulation to the laminar corium. (Radiographs: Debra Taylor, Auburn University)

In most horses, the easiest place to take the pulse is on either side of the leg just above the fetlock, between the suspensory ligament and the flexor tendons. There is an obvious groove between these two structures when the leg is weight bearing, and the best place to check pulses is just at the bottom of this groove. The main arteries of the leg are close to the surface in this location and there are convenient hard structures beneath the arteries against which to press them to detect the pulse. Taking the pulse involves applying light pressure to the area and waiting for a few seconds. A light, regular pulse should be felt. There is a corresponding location just below the fetlock (a depression between the flexor tendons and the extensor branch of the suspensory ligament), but this is more difficult to use in horses with feathers. A raised pulse in a leg indicates a problem below where the pulse is taken, so taking the pulse above the fetlock does not rule out a problem with the fetlock itself. Hence the location below the fetlock can be useful when narrowing down the causes of a raised pulse.

Fig. 20 Locations for taking a digital pulse.

The pulse should be taken at rest (preferably at least thirty minutes after any exercise, as exercise can create a raised pulse in a healthy horse) with the leg bearing weight. If necessary, the opposite leg should be lifted to ensure that the leg being checked remains weight bearing. It is helpful to know what is normal for an individual horse, and hence it is good practice for owners to check their horses’ resting pulse regularly. A normal pulse should be almost undetectable (some people can’t find a pulse in a healthy horse), although some people are better at detecting pulses than others. The resting heart rate of a horse (twenty-five to forty beats per minute) is somewhat slower than a human’s (sixty to seventy beats per minute) – which helps to identify if the person taking the pulse is accidentally feeling their own!

A raised pulse does not automatically signal the presence of laminitis. Other conditions such as abscesses, bad sole bruising and bone fractures, can cause a raised pulse. However, these other conditions usually only affect a single foot, whereas laminitis typically affects at least both front feet. As such, a raised pulse in both front feet (or both hinds for that matter) should raise suspicions of laminitis. Of course, bad sole bruising or abscessing can happen on both front feet simultaneously, but in such cases there is almost always some degree of laminitis involved, increasing the risk of the bruising or abscessing (this will be covered in the chapter on low-grade laminitis). It is also possible for a horse to have a raised digital pulse because it is overheating, perhaps due to the use of an overly thick rug, or to standing in the sun on a hot day, so this needs to be ruled out as a cause if a raised pulse is detected.

The typical description in laminitis is of a ‘bounding’ pulse, although less obvious pulses may be significant if they are above the normal level for that horse. In severe cases, especially in thin-skinned breeds such as the thoroughbred, the arteries can be seen pulsing with just the naked eye.

The Presence of Heat

Laminitic feet are typically hotter than normal. This can be difficult to feel because the hoof is a fairly good insulator, but with practice, the temperature of the foot can be gauged, and a raised temperature detected. It’s important to note that measuring the surface temperature of the hoof with an infra-red thermometer isn’t in itself useful in detecting laminitis, because the external temperature of the hoof is so highly affected by factors such as the ambient air temperature, and the temperature of the ground. The temperature also varies significantly over the different parts of the hoof. However, significant differences in temperature between the front and hind feet, or between the mid-wall in the toe and the heel, can be useful indicators of a problem. However, as with raised pulses, it’s important to note that the external temperature of the feet is often raised for some time after exercise, as the horse uses its legs and feet as radiators to ‘dump’ excess heat.

An Abnormal Stance

A horse with severe laminitis tends to stand with a very specific posture. Because the front feet are typically worst affected, and the toes more affected than the heels, the horse modifies its posture so as to take the weight off the front toes. In the classic laminitis stance, the front legs are stretched out in front of the horse with the toes either lightly touching the ground or lifted slightly off the ground. By the time the horse has adopted this stance, it is also usually looking quite distressed. The horse will often shake and shuffle from foot to foot, and may have a pained expression to the face.

Fig. 21 The typical stance of a severely laminitic horse.

Whilst the classic laminitis stance makes recognizing laminitis very easy, it only shows up in more serious cases. The lack of a laminitis stance does not preclude the possibility of laminitis, and some milder laminitics can have counter-intuitive posture problems, as described in later chapters.

An Abnormal Gait

A horse with laminitis will modify the way it moves to avoid pain. Vibration typically causes more pain to the horse than pressure. As a result, gait abnormalities are most pronounced when the horse is moving on hard ground, such as tarmac or concrete. Because the inflammation is concentrated in the toe area, the horse will try to move in a way that minimizes vibration to the toe. A healthy horse working on hard ground lands just heel first so as to make use of the shock-absorbing structures in the back part of the foot. A laminitic horse exaggerates this heel-first landing so as to absorb fully any vibration before the toe hits the ground. The result is an exaggerated heel-first landing that is sometimes described as a ‘toe flick’. It is useful to watch healthy horses in walk and trot to develop an eye for what a normal heel-first landing looks like. This makes it easier to pick up any subtle change towards an excessive heel-first landing.

Fig. 22 The foot at the point of impact. LEFT: A healthy horse with a normal heel-first landing. RIGHT: A laminitic horse with an excessive heel first landing.

Any horse with significant laminitis will tend not to want to trot, and if forced to, will do so in a way that minimizes impact on the feet. The horse typically appears to flatten the trot or even shuffle. In more severe cases, the horse may be reluctant to move at all, and may appear stiff throughout the body as it attempts to hold itself in an unnatural posture to reduce pain.

Other Diagnostic Techniques

Professionals involved in a suspected laminitis case may also use techniques such as hoof testers and nerve blocks to try to determine if the lameness is focused on the feet. Hoof testers apply a known amount of pressure to different parts of the foot, which allows detection of any tender areas. This is not a technique that should be attempted by anyone without appropriate training as it is difficult to be accurate and it is easy to inflict unnecessary pain on the horse if used incorrectly.

Nerve blocks involve injecting anaesthetic into the nerve just above the foot so as to numb the entire foot. If the horse then becomes sound,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.12.2019 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 94 colour photographs 30 diagrams and charts |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Medizin / Pharmazie | |

| Veterinärmedizin ► Pferd | |

| Schlagworte | causes of laminitus • Equine • equine healthcare • essential anatomy • Hoof • horse care • horse-centred laminitus • horse illness • horse wellfare • keeping horses • Laminitis • laminitus symptons • low grade lamintis • management of the foot • owning horses |

| ISBN-10 | 1-908809-87-6 / 1908809876 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-908809-87-2 / 9781908809872 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 53,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich