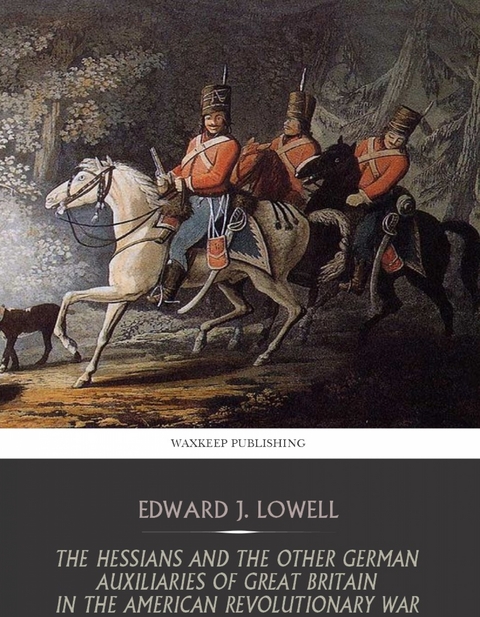

Hessians and the Other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War (eBook)

Charles River Editors (Verlag)

978-1-62539-036-3 (ISBN)

The Hessians were greatly feared mercenaries from Germany and they fought for the British in many of the battles of the American Revolutionary War. This version of Lowells The Hessians and Other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War includes a table of contents.

CHAPTER I: THE PRINCES

The little city of Cassel is one of the most attractive in North Germany to a passing stranger. Its galleries, its parks and gardens, and its great palaces are calculated to excite admiration and surprise. Here Napoleon III spent the months of his captivity amid scenes which might remind him of the magnificence of Versailles, which, indeed, those who planned the beautiful gardens had wished to imitate. For the grounds were mostly laid out and the buildings mainly constructed in the last century, when the court of France was the point towards which most princely eyes on the Continent were directed; and no court, perhaps, followed more assiduously or more closely, in outward show at least, in the path of the French court than that of the Landgraves of Hesse-Cassel. The expense of all these buildings and gardens was enormous, but there was generally money in the treasury. Yet the land was a poor land. The three or four hundred thousand inhabitants lived chiefly by the plough, but the Landgraves were in business. It was a profitable trade that they carried on, selling or letting out wares which were much in demand in that century, as in all centuries, for the Landgraves of Hesse-Cassel were dealers in men; thus it came to pass that Landgrave Frederick II and his subjects played a part in American history, and that “Hessian” became a household word, though not a title of honor, in the United States.

The Landgraves were not particular as to their market or their customers. In 1687 one of them let out a thousand soldiers to the Venetians fighting against the Turks. In 1702 nine thousand Hessians served under the maritime powers, and in 1706 eleven thousand five hundred men were in Italy. England was the best customer. Through a large part of the eighteenth century she had Hessians in her pay. Some of them were with the army of the Duke of Cumberland during the Pretender’s invasion in 1745; but it is stated that they refused to fight in that campaign for want of a cartel for the exchange of prisoners (Letter of Sir Joseph Yorke to the Earl of Suffolk, quoted in Kapp’s Soldatenhandel,” 1st ed. p. 229.) It would have been well for many of them had they declined to go to America for the same reason. So little was it a matter of patriotism, or of political preference, with the Landgraves, that in 1743 Hessian stood against Hessian, six thousand men serving in the army of King George II of England, and six thousand in the opposing force of the Emperor Charles VII.

The Landgraves of Hesse were not the only princes who dealt in troops. In the war of the American Revolution alone, six German rulers let out their soldiers to Great Britain. These were Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel; William, his son, the independent Count of Hesse-Hanau; Charles I, Duke of Brunswick; Frederick, Prince of Waldeck; Charles Alexander, Margrave of Anspach-Bayreuth ; and Frederick Augustus, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst. The action of these princes was opposed to the policy of the empire and to the moral sense of the age: but the emperor had no power to prevent it, for the subjection of those parts of Germany which were outside of his hereditary dominions was little more than nominal.

The map of Germany in the last century presents the most extraordinary patchwork. Across the northern part of the country, from its eastern to its western side, but not in an unbroken line, stretch the territories of the King of Prussia. The Austrian hereditary dominions, in a comparatively compact mass, occupy the southeastern corner. Beyond the boundaries of these two great powers, all is confusion. Electorates, duchies, bishoprics, the dominions of margraves, landgraves, princes, and free cities are inextricably jumbled together. There were nearly three hundred sovereignties in Germany, besides over fourteen hundred estates of Imperial Knights, holding immediately of the empire, and having many rights of sovereignty. Some of these three hundred states were not larger than townships in New England, many of them not larger than American counties. Nor was each of them compact in itself, for one dominion was often composed of several detached parcels of territory. Yet every little princedom had to maintain its petty prince, with his court and his army. The princes were practically despotic. The remnants of what had once been constitutional assemblies still existed in many places, but they represented at best but a small part of the population (The Landstande had more influence in Hesse than elsewhere. They are said to have tried in vain to obtain for the Country a share in the money received by the Landgrave for letting out troops. - Biedermann, “Deutschland im Achtzehnten jahrhundert,” vol. i. p. 114.) The cities and towns were governed by privileged classes. In the country some little freedom remained with the peasants of some neighborhoods as to the management of their village affairs, but in general the peasantry were not much better off than serfs, and subject to the tyranny of a horde of officials, who intermeddled in every important action of their lives. Trade was hampered by tolls and duties, for every little state had its own financial system. Commerce and manufactures were impeded by monopolies. In certain places sumptuary laws regulated the dress or the food of the people.

Before the last quarter of the century some improvement had taken place in the political condition of Germany. Frederick the Great of Prussia and Joseph II of Austria were, in their different ways, enlightened princes, and their example had stimulated many of the better sovereigns to exert themselves in some measure for the good of their people. The influence of the Liberal movement in France was also felt. But the idea of political freedom had hardly taken shape in the most cultivated of German minds. The good or evil disposition of the prince was no more under the control of the ordinary subject than the state of the weather. The doctrine of passive obedience was in fashion, though not entirely uncontested. If, as one writer on politics explained, it was the duty of the subject to submit in case his prince should take his life in mere wantonness, it was to be hoped that another writer was equally correct in saying that “in princely houses all virtues are hereditary.” (Biedermann, vol. i. pp. 161, 163, n.)

Let us now look a little nearer at those special inheritors of all the virtues who sent mercenaries to America. The most important of them was Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel (not to be confounded with his great namesake and contemporary of Prussia). This prince was the Catholic ruler of a Protestant country. His first wife had been an English princess, a daughter of George II. She had separated herself from the Landgrave on his conversion to Catholicism, and had retired to Hanau, with her precious son, of whom I shall presently speak.

Frederick had led a merry life of it at Cassel. He had taken unto himself a cast-off mistress of the Duc de Bouillon, but set up no pretensions to fidelity, and is said to have had more than a hundred children. A French theatre and opera, with a French corps de ballet, were maintained. French adventurers with good letters obtained a welcome and even responsible positions in the state. The court was ordered on a French model. French was, moreover, then, and has remained almost to our own day, the language of princes, courtiers, and diplomatists. In that language Frederick the Great corresponded with many of his relations, in it his sister wrote her private memoirs, and French was spoken at the court of that smaller Frederick whom we have in hand.

At the time of the American Revolution, the Landgrave was living with his second wife. He was about sixty years old, and seems to have become comparatively steady in his habits. He was a good man of business. His troops, drilled on the Prussian system, and recruited in a measure among his own subjects by conscription, were good soldiers. His army in 1781 numbered twenty-two thousand, while the population of his territories was little above three hundred thousand souls; but many foreigners were enticed into the service, and a few of the regiments were not kept permanently under the banners, but spent the larger part of the year disbanded, and met only for a few weeks of drill ("Briefe eines Reisenden.") Frederick took a personal interest in his army, and corresponded with his officers in America, making the hand and eye of the master usefully felt. He took pains with the internal affairs of his country, leaving, indeed, a full treasury at his death. He founded schools and museums, and, like all his family, loved costly buildings. When he sent twelve thousand men to America he diminished the taxes of his remaining subjects, and though these were sad and down-trodden, though they mourned their sons and brothers sent to fight in a strange quarrel beyond the sea, we may linger for a moment regretfully over Frederick of Hesse-Cassel, for he dealt in good wares, he showed some personal dignity, and he was one of the least disreputable of the princes who sent mercenaries to America.

William, the eldest son and heir apparent of Landgrave Frederick, governed at the time of the Revolution the independent county of Hanau, which lay a few miles to the eastward of the city of Frankfort. William was his father’s inferior in dignity and his equal in cupidity. As early as August, 1775, when the news of the battle of Bunker Hill must have been very fresh in Germany, the hereditary prince hastened to offer a regiment to George Ill, “without making the smallest condition.” In spite of his protestations of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Vor- und Frühgeschichte / Antike |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Vor- und Frühgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Altertum / Antike | |

| Schlagworte | americans • British • Germans • Independence • july 4th • Revolutionary War |

| ISBN-10 | 1-62539-036-X / 162539036X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-62539-036-3 / 9781625390363 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,6 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich