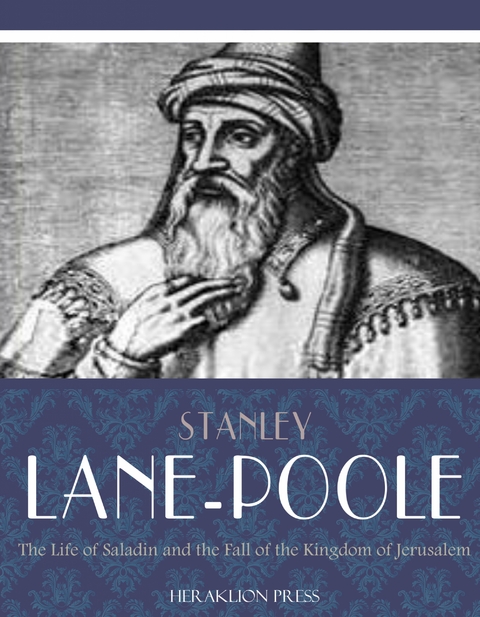

Life of Saladin and the Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (eBook)

Charles River Editors (Verlag)

978-1-63295-678-1 (ISBN)

The Life of Saladin and the Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem is a twenty-three chapter biography of the famous monarch.

CHAPTER II. THE FIRST CRUSADE. 1098.

MELIK SHAH, the great Seljuk Sultan, died in 1092, and civil war immediately broke out between his sons. Four years later, the First Crusade began its eastward march; in 1098 the great cities of Edessa and Antioch and many fortresses were taken; in 1099 the Christians regained possession of Jerusalem itself. In the next few years the greater part of Palestine and the coast of Syria, Tortosa (Antartus), Acre, Tripoli, and Sidon, fell into the hands of the Crusaders, and the conquest of Tyre in 1124 marked the apogee of their power. This rapid triumph was due partly to the physical superiority and personal courage of the men of the North, but even more to the lack of any organized resistance. Nizam-al-Mulk had died before his master, and there was no statesman competent to arrange the differences between the emperor’s heirs. Whilst the Seljuk princes were casting away their crown in fratricidal strife, the great vassals, though on the road to independence, had not yet learned their power: all were struggling for pieces of the broken diadem, each was jealous of his neighbor, but none was yet bold enough to lead. The founders of dynasties were in the field, but the dynasties were not yet founded. The Seljuk authority was still nominally supreme in Mesopotamia and northern Syria, and the numerous governors of cities and wardens of forts were only beginning to find out that the Seljuk authority was but the echo of a sonorous name, and that dominion was within the reach of the strongest.

It was a time of uncertainty and hesitation—of amazed attendance upon the dying struggles of a mighty empire; an interregnum of chaos until the new forces should have gathered their strength; in short, it was the precise moment when a successful invasion from Europe was possible. A generation earlier, the Seljuk power was inexpugnable. A generation later, a Zengy or a Nur-al-din, firmly established in the Syrian seats of the Seljuks, would probably have driven the invaders into the sea. A lucky star led the preachers of the First Crusade to seize an opportunity of which they hardly realized the significance. Peter the Hermit and Urban II chose the auspicious moment with a sagacity as unerring as if they had made a profound study of Asiatic politics. The Crusades penetrated like a wedge between the old wood and the new, and for a while seemed to cleave the trunk of Mohammedan empire into splinters.

Seven years before the birth of Saladin, when Fulk of Anjou ascended the throne of Jerusalem in 1131, the Latin Kingdom was still in its zenith. Syria and Upper Mesopotamia lay at the feet of the Crusaders, whose almost daily raids reached from Maridin and Amid in Diyar-Bekr to al-Arish and “the brook of Egypt”. Yet the country was not really subdued. The Crusaders contented themselves with a partial occupation, and whilst they held the coast lands and many fortresses in the interior, as far as the Jordan and Lebanon, they did not seriously set about a thorough conquest. The great cities, Aleppo, Damascus, Hamah, Emesa, were still in Moslem hands, and were never taken by the Christians, though their reduction must certainly have been possible at more than one crisis. The only great city which the Crusaders held in the interior, besides Jerusalem, was Edessa, and this they were soon to lose. The Latin Kingdom, with its subordinate principalities, counties, baronies, and fiefs, was more an armed occupation than a systematic conquest; yet even as an occupation it was inefficient.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem

At the time of its greatest extent, the “Frankish” dominion extended along a zone over five hundred miles long from north to south, but rarely more, and often less, than fifty miles broad. In the north the County of Edessa (al-Ruha, Orfa) stretched from (and often over) the borders of Diyar-Bekr to a point not far north of Aleppo, and included such important fiefs as Saruj, Tell-Bashir (Turbessel), Samosata, and Ayn-Tab (Hatap). West and south of the County of Edessa lay the Principality of Antioch, which at one time included Tarsus and Adana in Cilicia, but usually extended from the Pyramus along the sea-coast to a little north of Margat, and inland to near the Mohammedan cities, Aleppo and Hamah; among its chief fiefs were Atharib (Cerep), Maarra, Apamea, with the port of Ladikiya (Laodicea). South again of Antioch was the County of Tripolis, a narrow strip between the Lebanon and the Mediterranean, including Margat (Markab), Tortosa, Crac des Chevaliers, Tripolis, and Jubayl. Over all these states, as over-lord, stood the King of Jerusalem, whose own dominions stretched from Beirut past Sidon, Tyre, Acre, Caesarea, Arsuf, Jaffa, to the Egyptian frontier fortress Ascalon, and were bounded generally on the east by the valley of the Jordan and the Dead Sea.

The chief subdivisions were the County of Jaffa and Ascalon (including also the fortresses of Ibelin, Blanche Garde, and Mirabel, and the towns of Gaza, Lydda, and Ramla; the Lordship of Karak (Crac) and Shaubak (Mont Real), two outlying fortresses beyond the Dead Sea, cutting the caravan route from Damascus to Egypt; the Principality of Galilee, including Tiberias, Safed, Kawkab (Belvoir), and other strongholds; the Lordship of Sidon; and the minor fiefs of Toron, Baysan (Bethshan), Nablus, etc.

A glance at the map will show that a large proportion of these Christian possessions were within a day’s, or at most two days’ march of a Mohammedan city or a garrisoned fort, from which frequent raids were to be expected in retaliation for the incursions of the Franks.

The autobiography of one of Saladin’s elder contemporaries, the Arab Usamah, reveals a perpetual state of guerilla encounters, alternating with periods of comparative friendliness and tranquility. The general tendency of the original settlers of the First Crusade was undoubtedly towards amicable relations with their Moslem neighbors.

The great majority of the cultivators of the soil in the Christian territories were of course Mohammedans, and constant intercourse with them, and social and domestic relations of the most intimate nature, tended to diminish points of difference and emphasize common interests and common virtues. In the present day a European family can rarely live to the third generation in the East without becoming more or less orientalized. The early Crusaders, after thirty years’ residence in Syria, had become very much assimilated in character and habits to the people whom they had partly conquered, among whom they lived, and whose daughters they did not disdain to marry; they were growing into Levantines; they were known as Pullani or Creoles.

The Mohammedans, on their side, were scarcely less tolerant; they could hardly approve of marriage with the “polytheists”, as they called the Trinitarians; but they were quite ready to work for them and take their pay, and many a Moslem ruler found it convenient to form alliances with the Franks even against his Mohammedan neighbors.

Osama of Sheyzar

We find this interesting approximation between the rival races clearly appreciated in the fascinating memoirs of the nonagenarian Usamah, the Arab prince of Shayzar. As an historical witness, Usamah was fortunate in his epoch. He was born in 1095, three years before the capture of Antioch gave the Franks le point d’appui whence they advanced to the conquest of Jerusalem; and he died in 1188, when the Holy City had just been retaken by Saladin. He witnessed nearly the complete tide, the flow and ebb, of Crusading effort. His long life of ninety-three years embraced the whole period of the Latin rule at Jerusalem, and only just missed the Crusade of Richard Coeur de Lion. His family, the Beny Munkidh, were the hereditary lords of the rocky fortress of Shayzar, the ruins of which still overhang the Orontes. Strong as the castle was,—shielded by a bold bluff of the Ansariya mountains, approachable only by a horsepath, which crossed the river, then tunneled through the rock, and was again protected by a deep dyke crossed by a plank bridge,—its situation in the immediate neighborhood of Christian garrisons, half-way between the Crusading centres of Antioch and Tripoli, brought it into perilous contact with the forays that passed perpetually beneath its battlements.

Shayzar was one of those little border states, between the Moslem and the Christian, which found their safest policy in tempering orthodoxy with diplomacy. No better post of speculation could have been chosen from which to observe the struggle that went on unceasingly throughout the twelfth century; no witness more competent or more opportune could be found than the Arab chief who surveyed the contest from his conning-tower of Shayzar. He knew all the great leaders in the war, and often took part in the fray. His first battle was fought under that truculent Turkman, Il-Ghazy, the man who did more than anyone, before the coming of Zangy (=Zengi), to spread dismay through the Christian ranks. Usamah served under Zengy himself, and was actually present in the famous flight over the Tigris into Tekrit when the timely succor of Ayyub made the fortunes of the house of Saladin. He had seen Tancred more than once, when the prince led an assault against Sheyzar (=Shaizar); and he remembered the beautiful horse which the Crusader received as a present from its castellan. King Baldwin du Bourg was a prisoner in the fortress for some months in 1124, and rewarded his host’s kindness, more francorum, by breaking all his engagements...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Mittelalter |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter | |

| Schlagworte | Barbarossa • Biography • crusade • Egypt • Free • kings crusade • Richard |

| ISBN-10 | 1-63295-678-0 / 1632956780 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-63295-678-1 / 9781632956781 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,8 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich