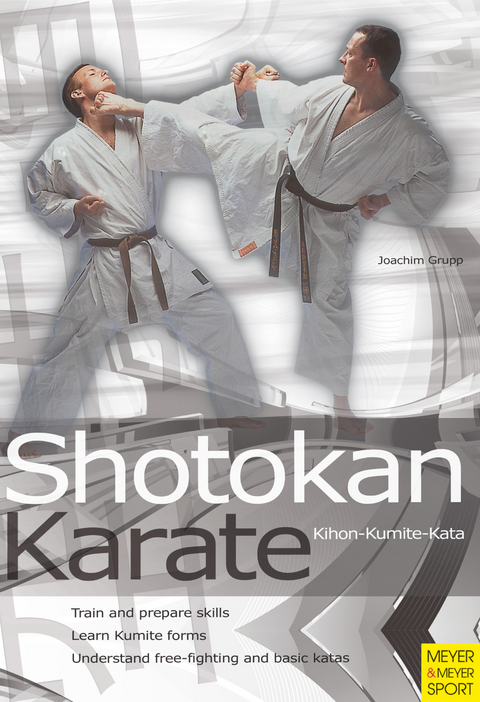

Shotokan Karate (eBook)

160 Seiten

Meyer & Meyer (Verlag)

978-1-84126-963-4 (ISBN)

Joachim Grupp has been practising Karate since 1976. He holds a 5th Dan in Shotokan Karate and is an instructor in a Karate Club in Berlin. He has been successful in national and regional competitions.

Joachim Grupp has been practising Karate since 1976. He holds a 5th Dan in Shotokan Karate and is an instructor in a Karate Club in Berlin. He has been successful in national and regional competitions.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 History of Shotokan Karate

1.1.1 Okinawa-Te – the Origin of Modern Karate

Karate-Do as we know it today is a type of martial art steeped in tradition, but it is nonetheless relatively new. A glance at its history shows how this apparent contradiction can be explained.

Okinawa, which is the country of origin for Karate, is the largest of the Ryukyu group of islands and lies about 500 kilometres from the Japanese island Kyushu and about 800 kilometres off Foochow on the Chinese mainland.

The island, whose inhabitants lived mainly from fishing and agriculture as well as trade with neighbouring countries, was divided into three kingdoms up until the 15th Century. These provinces – Chuzan, Nanzan and Hokuzan – waged violent war amongst themselves. Even before the unification of the three regions in 1429 under the king of Chuzan, Sho Hashi, the island occupied an important position as the centre of flourishing trade with the neighbouring countries of China, Korea, Taiwan and Japan due to its geographical location. The influx of cultural and political influences associated with the import trade also contributed to the spread of regional martial arts from other Asiatic countries into certain regions of Okinawa.

While this influence centred itself around the commercial centres of Shuri, Naha and Tomari, it nevertheless helped the widely different martial arts gain enormous popularity. Worthy of mention in this connection is the knowledge of handling weapons, which came to Okinawa with Japanese refugees as early as the 10th century. There is the bow and arrow, use of the sword (Katana and Tachi) and the numerous hard and soft styles of the Chinese art of Chuan-Fa, which is considered the forerunner of today's Kung-Fu.

Even if, in several versions of the history of Karate, it is erroneously maintained that the Chinese taught martial arts to the inhabitants of Okinawa and that they then developed the system of Karate from this, those better informed insist that the older martial art of Te (Te=hand) already existed on Okinawa and was taught there by several masters. It is less probable that the Chinese – who considered themselves socially and culturally superior – systematically gave instruction in these arts. It is more likely that the Chinese influence worked more indirectly. Thus, the various Okinawan envoys from the regent King Satto brought back elements of Chinese martial arts to the island in 1372. Here, the martial arts were always only practised by a few in small schools and passed on in family circles or amongst friends. This would also explain the different versions that can be found in the native Te. It cannot be said that Te became something like a popular sport, as it was a martial art practised by only a few select insiders.

A direct Chinese influence came when a group of 36 Chinese families settled in a vicinity of Naha called Kumemura in 1392. From here, they introduced the local inhabitants to Zen Buddhism, teaching them their religion and philosophy. It is possible that they had an influence on the development of Te in the Naha region. It is held that the local popular Naha-Te (later called Shorei-Ryu – 'Ryu' means 'school' or 'way of') was inspired from the traditions of Chuan-Fa. It consists of dynamic movements and puts value on breathing and the technique of producing rapid and explosive power. Other centres for Te were Tomari and Shuri (the styles developed here were later also called Shorin-Ryu). A Chinese influence could also be found in Shuri-Te, with its emphasis on breathing control and round defensive movements. Tomari-Te contains both these elements and concentrates on flexible, rapid movements.

The American author Randall HASSELL, who has written one of the best-researched books about the history of Shotokan, separates the local native techniques of Te into two different martial art systems. The one style, preferred by the rural inhabitants, uses a low stance so that defence is executed from low down with the arms and legs, while the other more powerful style uses numerous strong arm movements and can be traced back to the fishermen.

In addition, the inhabitants of Okinawa were very creative in the use of their tools as weapons against the marauding Samurai and against plundering invaders and pirates. The use of these tools as defensive instruments was called Kobudo, and they consisted of items such as Bo, Tonfa, Nunchaku, Eku, Kama, Kusarigama and other equipment. Depending on the type of "weapon", these permitted close-quarter and distant fighting. Many Kata techniques still contain defensive quarter and distant fighting. Many Kata techniques still contain defensive movements against attacks carried out using these "tools". When using weapons was first banned during the reign of Sho Shin (1477-1526), these tools were replaced with unobtrusive, harmless everyday fishing and farming implements, and these skills and unarmed defensive combat became popular.

The strong Japanese influence after the occupation of the island by the Ieshisa Shimazu clan in 1609 (also called the period of control by the Satsuma dynasty) brought considerable suppression of the populace. Even the use of ceremonial swords and the arming of servants of the state was forbidden. The population stood literally "empty handed".

Changing occupying forces, suppression by new rulers and the necessity to defend oneself against often life-threatening attacks made Te and Kobudo more popular. This always occurred in small circles, which developed their own system in such a way that they were enough to meet their particular defensive requirements. The efficiency of unarmed combat also led the Japanese to ban it.

The masters of the various systems could therefore only pass on their knowledge in secret, which again prevented the development of a standardised "Okinawa style". The population held these masters in great respect. Some masters passed on the techniques in the form of encoded movement sequences called Kata. Today's common interpretation of the term Kata as 'form, sequence' is inadequate. Constant practice of the movements until perfection served to improve the technique and control of the body. It was the dividing line in emergencies against armed aggressors and was the difference between life or death. In order to improve their techniques, the Okinawans used several aids. The best known of these was the Makiwara, a punching bag fixed to a post. To master Te it was necessary to be able to distinguish amongst the possible techniques and to be able to concentrate totally on the right one so that the aggressor was put out of action with the first blow. It was often the case that the aggressors were heavily armed Samurai, who tried to fill their own war coffers at the expense of the people.

The end of the Satsuma regime in 1872 and the Meiji government reforms in Japan in 1868 created a liberalisation of all of Japanese society, and all of the principles of the feudalistic class society were done away with. Modern transport means, emerging worldwide trade and, with it, contact with other continents and cultures exposed Japanese society and its values to the rest of the world.

When Okinawa officially became part of Japan in 1875, the island also profited from this exposure. Naturally this also included Okinawa-Te or Tang-Te, as the unarmed art on Okinawa was called after the Tang dynasty (Tang=Chinese). From this time, Te could officially be freely practised. In order to understand modern Karate properly, it is necessary to remember the fact that the Japanese, while exercising control over the island as part of Japan, always distrusted Okinawan culture, did not recognise it or scorned it as being backward.

At the end of the 19th century, one could not speak of a standardised style of martial art in Okinawa. As already mentioned, over the course of the century a large number of schools and styles had been developed, of which Naha-Te, Shuri-Te and Tomari-Te were the most well-known. It is difficult in today's terms to call the Te forms different styles, since the repertoire of some masters consisted of either only a single or very few techniques. It is reported that one master spent his whole life practising a blow using the elbow. Sometimes the farmers or fishermen who used these blows or kicks were well-known for one single technique. They had practised it for all their lives and perfected it with great efficiency. On the other hand, there were masters who had begun to develop complete systems.

The historian REILLY tells us that there was great rivalry between the large schools of Shuri-Te, Naha-Te and Tomari-Te following their official recognition as arts. Quarrels between the various schools added to damaging the esteem of Te on Okinawa. Despite this, the popularity of (Kara-) Te grew. Shintaro Ogawa, the official responsible for school education in the prefecture of Kagoshima, appointed the Master Anko Itosu to be "Instructor of Training" in the elementary schools. He had been impressed by a demonstration performed by a young man whose group of pupils showed extraordinarily good body conditioning. His name was Gichin FUNAKOSHI. In 1902, (Kara-) Te became a school sport on Okinawa.

1.1.2 Modern Karate Comes into Being

Whereas the original aim of Te was the physical destruction of the (often armed) opponent, its development as a school sport marked a turning point. Not only did it mean that there was a change from being something secretive and only available to a selected few to being an official part of the school curriculum; it also heralded the change from being a deadly fighting method to being a type of sport that serves to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.3.2009 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Aachen |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Kampfsport / Selbstverteidigung |

| Schlagworte | Karate • Martial Arts • Self Defense • Shotokan Karate • Sport |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84126-963-8 / 1841269638 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84126-963-4 / 9781841269634 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 16,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich