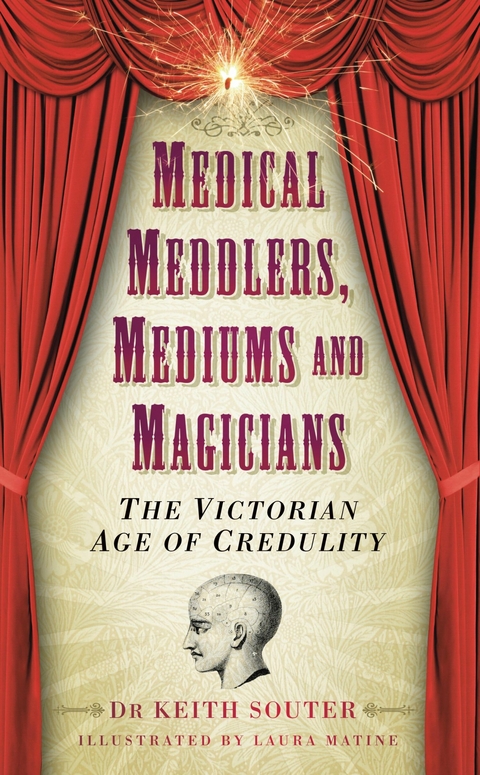

Medical Meddlers, Mediums and Magicians (eBook)

288 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-7807-4 (ISBN)

INTRODUCTION

Before We Lift The Curtain Or Attempt To Part The Misty Veil

An introduction to credulity

Before we start on our journey it would make sense to consider some of the reasons why the Victorians were so willing to believe in the claims of quacks and the table knocking that they heard during séances, and be convinced that the illusionists who performed in the theatres and music halls were capable of actual magic.

A small group at a séance.

During the Victorian age the thirst for knowledge and discovery seemed insatiable. Built upon the Industrial Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment it was a great age ruled over by Queen Victoria and, until his death, her husband Albert, the prince consort. In all areas of life pioneers were pushing back the frontiers of knowledge and improving transport, communication, engineering and architecture. Steam power, gas, electricity, anaesthetics and aseptic surgery promised to make the world a better and safer place to live in. Perhaps most significantly, Charles Darwin developed his theory of evolution and published his ground-breaking book On the Origin of Species, which shook the very foundations of religion and belief.

The expanding British Empire meant that maps were continually being redrawn in order to show the spread of pink, showing the extent of the empire upon which the sun never set. People were proud and patriotic. Yet it was also a time when children were sent up chimneys, down mines and made to work unbearably long hours when they should have been playing or learning. It was a time when we had workhouses, appalling slums and prisons where both men and women were sent to do hard labour. This huge inequality in society stimulated men and women to do their utmost to bring about social reforms. It was a slow process.

It is perhaps because there was so much change going on and so many discoveries being made that people were open to all sorts of ideas. The truth is that although advances were being made in many sciences, medicine lagged behind. The germ theory of disease was not proposed until late in the nineteenth century, so there was fertile ground for all manner of theories about health. Medicine was a very inexact science and until 1858 the medical profession was totally unregulated.

Medical meddlers or out and out quacks peddled all manner of potions, nostrums and elixirs to cure all sorts of ailments, from baldness to impotence, from piles to gangrene, and from syphilis to death itself.

Death was of course always on people’s minds, since there was incredibly high infant mortality, there were epidemics and there were casualties from the many wars that were fought to extend and protect the empire’s dominions. Mediums and clairvoyants preyed on the recently bereaved in séance parlours and village halls and seemed adept at parting the misty veil between the world of the living and the dead. They talked with the departed and produced ghostly phenomena or even manifested the spirits themselves.

CREDULITY

Not all of the people who practiced outré medical arts were quacks and charlatans. Neither were all of the mediums deliberate frauds. Certainly the vast majority of conjurors and illusionists never claimed to be anything other than entertainers, yet there are common threads linking the three areas. The backdrop against which they were all played was that of human credulity.

Credulity means the willingness to believe in something or in someone based on fairly scant evidence. While it can be considered as a good quality, more often people regard it as a weakness. Children naturally tend to be trusting in their parents and their family, but they have to be taught to be wary of strangers. This is sensible, since not everyone is trustworthy. Adults who remain credulous could be vulnerable to others who may gain some advantage by wilfully deceiving them.

People do vary in their credulity. It is a complex matter that has many elements. Although it is an artificial gradation you can virtually divide people into four types – sceptical, open-minded, willing dupe, or totally gullible. I am sure that you will recognise friends and family who fall into one or other group.

Credulity can also vary in any individual from time to time. Belief in a god is an example. When people are bereaved they are more likely to seek solace in religion, in the belief that the deceased will not simply cease to exist. Similarly, faced with illness that will not respond to medication they may accept the assurance about some other treatment from someone who seems knowledgeable, or from someone who received benefit from that treatment.

A gambler may be an out and out rationalist, yet when having a flutter he may ask Lady Luck to help him. People believe in lucky charms, talismans and good-luck tokens.

In the Victorian age we knew less about the laws of science or about the causes of illness. People may have felt less secure about reaching their allotted life span, and they were less sure that illnesses were not under the control of deities or spirits. The world was an altogether more mysterious place and many more things were possible.

PLAUSIBILITY

This goes hand in hand with credulity. Plausibility means whether something seems to be possible or acceptable.

When someone tries to persuade you to use a particular treatment then the way they explain its benefits will be extremely important. If they can persuade you that it sounds plausible then there is a good chance that it will work.

If someone gives a good explanation of the way in which the living and the dead can both exist then you may be persuaded to attend a séance. You may be willing to accept all that you see and hear at the event.

A medical theory or a philosophy, if it seems in accord with known science and the currently accepted understanding of the way that things work, will seem more plausible. This was the case with phrenology, the study of character through analysis of the contours of the lumps and bumps on the skull. It seemed plausible based on the Victorian understanding about the brain and the huge interest in anthropology that was generated by explorers and those who followed Darwin’s theories about evolution. Similarly, homoeopathy, the system of medicine based upon the principle of treating ‘like with like’, seemed intensely credible. Interestingly, of the two practices, phrenology (which seemed most plausible) died out while homoeopathy still thrives around the world, albeit continually dogged by controversy.

SUGGESTIBILITY

This is an interesting phenomenon that links credulity with plausibility. In normal consciousness we use various mental mechanisms that together make up our critical faculty. We use this in order to balance our credulity with what seems to be plausible.

In a hypnotic trance, one goes into a relaxed state in which the critical faculty ceases to operate at a normal level. For example, if you are given a pencil to hold when you are fully conscious, and told that the pencil will gradually get hotter and hotter, then your critical faculty will tell you that this is not plausible because pencils have no means of getting hotter of their own accord. If you are then put into a light hypnotic trance and again handed the pencil with the same suggestion that it will get hotter and hotter, then you probably would feel it getting hotter and hotter until you could no longer hold it. The pencil has not become hot, of course, rather your critical faculty has ceased to work so that you do not criticise the suggestion and it seems to be plausible. The result is that you respond to the suggestion.

This is not to say that during Victorian times people were hypnotised into thinking that things would work. There are other circumstances in which suggestibility increases. One such condition is in crowds united for a single purpose. An audience will often accept the illusion of the magician. A group listening to someone expound about the merits of a patent treatment at a medicine show may respond to the suggestions given. Similarly, people attending a séance may enter a trance-like state and suspend their critical faculty, so that they become open to all manner of things that they see and hear.

THE PLACEBO EFFECT

This is highly relevant to our consideration about medical meddlers. A placebo is an ineffective drug or treatment that somehow makes the patient feel better. The world comes from the Latin placere, meaning ‘to please’.

The placebo effect is a fascinating phenomenon, possibly the most fascinating phenomenon in medicine. For some reason (possibly for many reasons, including those that we have just considered) an individual will respond to an inactive agent in a very positive manner. Nowadays placebos are used in scientific trials, usually double-blind trials, in which neither the patient nor the doctor knows whether they are being given an active agent or a placebo. This sort of trial is used to assess whether a drug (the active agent) is superior to the placebo, i.e., better than nothing. The problem is that a placebo response can occur in anything between 25 and 70 per cent of cases. The frequently reported placebo response is 30 per cent, but it depends upon many factors. In general, the more dramatic the treatment, the greater the placebo response. It is also thought that the more the treatment is ‘sold’ by the enthusiasm of the practitioner the greater the placebo effect will be.

ILLUSION

Magicians specialise in the art of illusion. Essentially they present an effect that seems to operate by unseen means, by the power of magic. It is, however, just a trick. The point is that...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.11.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Alternative Heilverfahren |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Lebenshilfe / Lebensführung | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | conjurers • Credulity • Disease • Diversion • Entertainment • Fraud • frauds • Fraudsters • fraudulent • gullible • Illusionists • Knowledge • mediums • Mortality • music halls • Panaceas • quack doctors • Quacks • The Victorian Age of Credulity • Tricksters • Victorian • Victoriana • Victorian Era • victorians • victorians, victorian era, victorian, knowledge, gullible, credulity, disease, mortality, quacks, quack doctors, panaceas, mediums, diversion, entertainment, conjurers, illusionists, music halls, tricksters, fraudulent, frauds, fraud, fraudsters • victorians, victorian era, victorian, knowledge, gullible, credulity, disease, mortality, quacks, quack doctors, panaceas, mediums, diversion, entertainment, conjurers, illusionists, music halls, tricksters, fraudulent, frauds, fraud, fraudsters, The Victorian Age of Credulity, victoriana |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-7807-9 / 0752478079 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-7807-4 / 9780752478074 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich