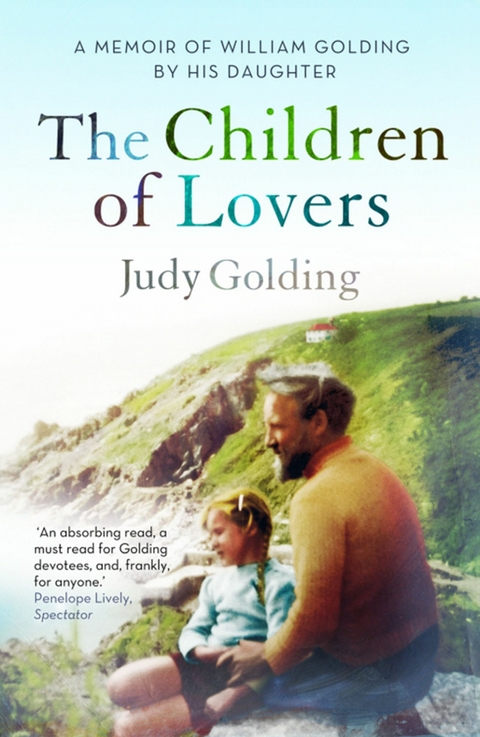

Children of Lovers (eBook)

272 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-27341-6 (ISBN)

Judy Golding was born in Marlborough, Wiltshire, in 1945 and grew up near Salisbury, where her parents worked as teachers. She read English at the University of Sussex and St Anne's College, Oxford, and in 1971 she married an American studying politics at Balliol. Subsequently, she worked as a copy editor for Oxford University Press and Jonathan Cape. She and her husband have three sons and three grandchildren and live in Bristol.

'The Children of Lovers are Orphans.' ProverbBestselling novelist, author of Lord of the Flies, William Golding was a famously acute observer of children. What was it like to be his daughter?In this frank and engaging family memoir, Judy Golding recalls growing up with a brilliant, loving, sometimes difficult parent. The years of her childhood and adolescence saw her father change from an impecunious schoolteacher to a famous novelist. Once adult, she came to understand some of the internal conflicts which led to his writing. The Golding family life, both ordinary and extraordinary, always kept its characteristic warmth, humour, complexity, anger and love, danger and insecurity. This is a book about family and parents, about lovers and their children, and about our impact on one another - for good or ill.

Judy Golding was born in Marlborough, Wiltshire, in 1945 and grew up near Salisbury, where her parents worked as teachers. She read English at the University of Sussex and St. Anne's College, Oxford, and in 1971 she married an American studying politics as Balliol. Subsequently, she worked as a copyeditor for Oxford University Press and Jonathan Cape. She and her husband have three sons and one grandson and live in Bristol.

It is 1950 and I am five. Far above me, my mother’s perfect face is revealed to the startled bus conductor. She puts my bag in the luggage space, then jumps off the giant double-decker, the red number 9 to Marlborough. She waves goodbye. She doesn’t usually smile at me like that, but the other passengers think, what a nice young woman.

Marlborough is an hour and a half away. I hope no one will talk to me. The conductor is bound to, so I clutch my paper strip giving me the right to travel the twenty-seven miles. I can show it wordlessly, discouraging any well-intentioned reassurance which would actually not reassure me.

The sun is setting. It will be dark when we get to Marlborough. Alec will meet me – Alec, my grandfather. It never occurs to me to doubt that he will be there, peering at the bus.

Just before Marlborough, the bus shoots along the edge of Savernake Forest, with its fast straight road, its tall beech and oak. The top of the bus rattles the branches. Then we hurtle down the big hill towards the clustered roofs, we slow down over the bridges, we trundle along the south side of the High Street. By St Peter’s Church we do a rocking swerve round the corner. We regain our balance and come to rest at the bus stop near the Castle and Ball hotel. Alec gruffly kisses me. His cheek is a bit like sandpaper. He shaves in the morning and by now the stubble has grown again. I recall the sound of his cut-throat razor, rasping over his cheek.

We walk home, past the shops, carefully crossing Kingsbury Street on the corner where Alec once saw a man knocked down. We dive under the tunnel that goes past Calvert’s, the store with the faded raincoats and old-fashioned hats. Now, on either side of us, are the two sections of the graveyard. I don’t give a thought to the bodies in the earth, even when I glimpse their gravestones. Alec completely removes the uncanny.

We arrive at the green wooden porch on the south wall of 29 The Green. Nowadays there is no door, no porch, only bricks. The little porch vanished in the 1960s, when the house was gutted and became an ordinary place. In the hall is the shadowy figure of my grandmother. She bends down and kisses me. Her face is cool and wrinkled, ancient beyond imagination. She says little. I am shy of her. Now I realise she was shy of me.

*

Later, when I was seven, my mother would take me out to the bus stop and leave me there. The first time she did this, I assumed that she had arranged things, had perhaps told the bus driver in some magical way. It was clear to me that there was a vast league of grown-ups who knew everything, whose loyalty to each other was absolute. So I watched the enormous double-decker go by, not understanding that I ought to stick out my arm. But I learnt to do it, and if the bus was late I would see her come and look over our tall garden fence, see me and go away again.

When I came home to Salisbury on Sunday, Alec would come too. He would shepherd me into the flat, and turn straight back to the bus stop, catching the bus on its return journey to Marlborough. He said this was because the bus route didn’t terminate at our stop, as it did at Marlborough. It might have swept me on down into the town where there were perils like drunken soldiers. Actually, I think he declined to be responsible for putting me on the bus on my own.

My mother often said how brave it was of me to travel on my own, perhaps hoping that if she said it often enough, it would become true. In reality I felt there was no choice. She wanted me to be adventurous, as she was. No doubt she believed the solitary journeys to Marlborough would make this happen. Sadly, I think it did the opposite. It made me distrustful of strangers, and fearful of solitude, as I still am. I have had to learn that independence is a pleasure. What it did teach me was a love of travelling, and a practised absorption in fantasy. I didn’t need a book on these journeys – indeed I didn’t like having one. I preferred to launch myself into thought – I could examine things in detail when they were non-existent or miles away. I could travel in sunlight, while the bus rattled on in darkness.

She did what she could with me, I expect, but she was not motherly by nature. Perhaps nobody is. She fed me herself till I was a year and a half. I have a very ancient memory of an oblong pinkish-brown object, three-cornered and large. I recognised it when I was feeding my first child. It is a human nipple, moulded by a baby’s mouth. She made me lovely dresses, tried to deal with my agonising ear infections, my colds and coughs, my – to her – alien fears. She tried to ensure that my mediocre looks would not be further eroded. But I could always tell. It was a bit like having a stepmother – not a wicked one, just someone who was naturally more interested in her relationship with her husband than she was in the connection she had with his children – or, at any rate, with his daughter. I think she really was fond of David.

And it never occurred to me at that stage, when I was small, to wonder if my father felt the same way. He was sometimes abrupt, even cold, sometimes inexplicably hostile. But palpable affection rose off him rather like steam, and it made me love him with passion, as I did Alec, and for much the same reason. My feelings extended to everything about the two of them: voice, smell, hair, hands, face – and their clothes, which I thought expressed their nature so strongly, their ancient sports jackets, flannels, shirt and tie, their worn brown shoes.

My father and Alec mostly wore the same set of clothes every day. Neither of them considered clothes important. Both hated new ones. Grandma, despite my mother’s encouragement and persuasion, felt the same way. But they all accepted my mother’s delight in the whole business, her skill and taste. They felt people were entitled to scope if they were good at something. Of course, sometimes there was competition and that was not good. But clothes were not a matter for rivalry. If you had seen my mother surrounded by Goldings, you might have thought of a butterfly on a pile of dead leaves.

In the post-war years, my parents were so poor that my father still wore his naval clothes. We have a photo of him in 1951; it was taken during the Festival of Britain, and he is holding up a Union Flag tied on to a boat hook, which he is going to fix in a tree – he was always profoundly patriotic. He is wearing a flapping pair of white knee-length shorts – they were for tropical use and my father had been issued with them for his brief stay off Port Said in 1943. I expect he pictured the naval officer from the final scene of Lord of the Flies wearing them. In the photograph he is cheerfully oblivious, wearing what looks like a badly cut skirt.

I admired his disregard for the whole business of clothes, and I imitated him, unsuccessfully, since in my heart of hearts I rather liked them. But I wished passionately to be a part of that world, the warm, exciting world of tweed jackets and tobacco, deep voices and excitement. I did not so much want to be a boy as long to be a man, to be among them. I still catch myself now, more than half a century later, adopting a pose that I think of as masculine. From somewhere I acquired the unfounded belief that my pseudo-masculinity would be likeable. Since I wanted men to like me – my father in particular – I should have learnt to be like my mother, with her weekly hair appointments, her clothes, her striking make-up. But I knew – without articulating the thought to myself – that this would be no good either. It would merely provide my father with another problem – how to notice my appearance without offending my mother. Instead, I developed a sort of travesty identity, a pageboy persona, like Viola in Twelfth Night. I acquired the proper clothes diligently, in a parody of my mother, among my brother’s cast-offs or from jumble sales. No one ever told me I should do this. But I knew it was the way.

As I grew older it became difficult to unlearn the habit. I found it impossible to believe that looking like a girl would be welcomed. And yet my mother made me pink dresses with puff sleeves, or very short velvet dresses with blond lace collars, outfits that I can see now had a kind of lollipop suggestiveness. It was all very puzzling. My father silently disapproved. My mother dressed me up as a dolly – an obedient one.

Secretly, wickedly, I found her frustrating and irritating. When I was about eight, I had a dream. There she was, talking away brightly, when, suddenly, her head fell off – to one side, I remember, and with rather a thump. This is so embarrassingly Freudian that I have never mentioned it before. I didn’t hate her. I simply knew I couldn’t rely on her because she wasn’t very interested. Clothes interested her, and so I was beautifully dressed. But one day, catching the bus to my little school in the Close (I was probably seven – I can’t have been older), I had a quarrel with another small girl at the bus stop and her mother shouted at me. I went home in tears and rang our doorbell. My mother leaned out of our upstairs window, and told me to stop crying at once and go off to school. Once I got to school, the tears became a cascade, and the teachers gathered round. Their questions were solicitous, so much so that I had to pretend I was crying because I’d forgotten my pinafore, another...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.4.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Families • relationships • writers |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-27341-6 / 0571273416 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-27341-6 / 9780571273416 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich