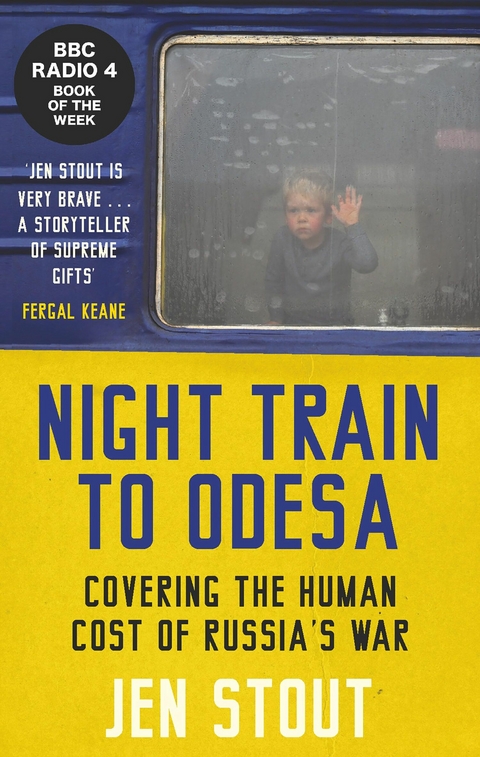

Night Train to Odesa (eBook)

256 Seiten

Polygon (Verlag)

978-1-78885-638-6 (ISBN)

Jen Stout is a journalist, writer, and radio producer from Scotland, frequently working in Ukraine. Originally from Shetland she has lived in Germany and Russia. Her empathetic and vivid coverage on the deportations in Kharkiv region was shortlisted for an Amnesty Media Award. Her first book, Night Train to Odesa, was a BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week, and won the Saltire Society First Book of the Year Award.

Jen Stout is a journalist, writer, and radio producer from Scotland, frequently working in Ukraine. Originally from Shetland she has lived in Germany and Russia. Her empathetic and vivid coverage on the deportations in Kharkiv region was shortlisted for an Amnesty Media Award. Her first book, Night Train to Odesa, was a BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week, and won the Saltire Society First Book of the Year Award.

FOREWORD TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

IT’S A STRANGE THING to watch this war from afar after being so immersed in it. Like so many, I often pore over the online military maps that show the steady creep of red in Ukraine’s east: Russian forces slowly gaining ground. It looks so distant, so clinical – but these are all real places, etched onto my mind. Looking at the area in the south-east corner of the country, I remember the vivid colour of the autumn leaves in the village of Yelyzavetivka, and the couple I met on the muddy road who were so resolute in their decision to stay put. I wonder if they’re still alive. Shelling in the village was heavy then, late 2022. How long can anyone survive in such a place?

Just to the north is Kurakhove, where I stood in the eerie evening quiet by the lake, watching skeins of geese fly over the tall towers of the coal-fired power plant; it has been bombed so many times now that it barely operates. The Russian army is approaching from the north and east. Not everyone can or will evacuate. What awaits them under Russian occupation is well-documented in these recent years: the mass graves and executions, the torture cells and the people who just disappear forever.

Much has happened since the spring of 2023 when this book ends, and little of it has given Ukrainians hope. The fall of Bakhmut, after a long, bloody siege, was a huge blow; it was followed by the catastrophic floods in southwest Ukraine when Russian forces blew up the Nova Kakhovka dam. Huge expectations were placed on the Ukrainian counteroffensive in June of that year, despite the dire warnings around ammunition shortages and entrenched Russian defensive positions. Losses on both sides were huge and Ukraine failed to break through in the south and east. Since then, the muttering in the west about ‘war fatigue’ and stagnation has grown louder; increasingly, there are calls for Ukraine to compromise and for western funding to wind down. Those who make these calls either don’t know what Russian occupation means in reality, or don’t care. At the time of writing, the demands made by Russian president Vladimir Putin are incompatible with any peace process: not just retaining the 18 per cent of Ukraine he already occupies, but actually taking back Kherson and the whole of Zaporizhzhia region, including the city of the same name – a city Russia has not yet managed to take. The idea that negotiations could start from this is absurd. So the war grinds on. Hopes of regime change in Russia have come to nothing. The internal drama of state-backed war-lord Yevgeniy Prigozhin and his march on Moscow ended with his death in a plane crash in 2023, and the small acts of civil resistance in Russia, those rare voices of protest, are always quickly crushed. A change of leadership for the Ukrainian army in November 2023 was followed by the loss of another major town in Donetsk region, Avdiivka. Like Bakhmut, it was wiped off the map during the fighting – just the grey rubble skeleton of a town left now.

And this is just the literal frontline, the shifting line on the map between a sea of red and a bulwark of blue. Actually, in Ukraine the frontline is everywhere, because the cities are attacked relentlessly, day and night, aerial bombs and ballistic missiles and drones falling on Odesa, Kharkiv, Kyiv, Dnipro, even Lviv in the west. It barely even makes the international news now. Attention long ago shifted to the Middle East, and the release of a 1.5-tonne bomb onto Kharkiv’s already-shattered city centre struggles to make it onto the running orders. I was there in the spring of 2024 when these bombs were falling, and it felt like hell, and then it felt like normality, the two states switching around several times a day. I could talk to my friend Nataliya on her pleasant, sunny balcony and watch her barely pause for breath as the explosion shuddered around us. I could meet another friend for a drink on famous Sumska Street, then find the way home with headtorches in the blackout, sirens screaming overhead. Nearly a year later it’s still like this. The biggest thing I’ve learned in this war is that people can get used to anything. Normality will insist on emerging again, perhaps because we so deeply need it.

There have been few bright spots for Ukraine in the last two years. One, though, is their extraordinary success in the Black Sea, pushing the Russian fleet back to the safety of its Crimean naval base. Another is the constant undermining of that Crimean safety, as fuel depots, bases and bridges on the occupied peninsula have come under relentless Ukrainian attack. Even more daring, the drone attacks and sabotage deep in Russian territory, and the incursion into Kursk region, have brought the war home to Russian people, giving them a taste of what Ukrainians have endured for so long.

What this book documents is a snapshot in time, from the start of the full-scale invasion to the summer of 2023. It was a terrible time in Ukraine, and I tried to describe what people were going through as clearly and honestly as possible. But also, it was a time of giddy hope: the all-encompassing kind that sweeps you up.

The wild, improbable success of the army’s counteroffensive in the northeast, late in 2022, saw great swathes of the map change back to blue, huge numbers of people freed from the hell of Russian occupation. Then the city of Kherson was liberated, another improbable triumph. Those videos of people in the streets of that Black Sea city, weeping, cheering the soldiers as they passed, holding up the blue and yellow flags they’d hid during occupation. It was happening. The tide was turning.

I was in Kharkiv that night, up in the northeast – often bombed but slightly safer now that the Russians had been pushed back to their own border. And I remember the mood there, in that mad mishmash city of factories and constructivism and artists and ideas; I remember the mood among the volunteers, the soldiers, my friends, down in a basement bar in the shattered city centre. Giddy. Tears and songs and real pride. Try to imagine the feeling: your society is facing down this Goliath, this terrifying mega-army – and winning. Against all odds and expectations. Anything seemed possible then.

Now, late 2024, the liberated city of Kherson is hell. The Russians practise their drone targeting on the few civilians left. As figures run down empty streets, attempting to reach a shop, the first-person-view drones follow, a black buzzing menace, hovering and swooping, picking people off one by one. Incinerating them in their cars, or on their bikes. The pilots are far away, in Russia. They post videos online, for fun, of the ‘target practice’. It’s like human safari.

It’s hard, then, to talk of hope. Hard to read the things I wrote in 2023, naive words hinting at optimism for the future, reconstruction, peace. I’m often asked what will happen next in the war, and my answer is always the same – it’s down to us. Whether our governments, our societies, fully back Ukraine, or abandon it, because this havering position in the middle is just a drawn-out version of the latter. But I am not a military strategist; I can have opinions on the rights and wrongs of what is happening, but I do not predict outcomes of wars or offensives. My job is to describe what it is actually like. In this book, that starts in Russia, which is appropriate, as Russia started it all. I am still trying to understand how a society can sink into such immorality, such casual acceptance of aggression and violence. It is rooted in the depthless cynicism of Soviet times, in the shame and humiliation of the 1990s, though none of that excuses it. I don’t dwell on Russia, though, because we have all spent far too long centering the Russian experience over the Ukrainian. To be in that country just as its tanks massed on the western borders, just as the propaganda pitch increased on every TV set, was instructive. But I was so infinitely glad to leave a few days after the full-scale invasion. I’d rather be in Donbas, in the free air of Ukraine, than spend one second back in stifling, cynical Moscow.

I’d rather be in eastern Ukraine, actually, than anywhere else. Travelling around the country in 2022 and 2023 I learned – in a haphazard way, and with the help of kind friends and colleagues – how to report in a war zone, and like countless others before me, I found I was very happy doing this. It suited me. That old cliché, the best and worst of humanity coming out sharp and clear in wartime, was very true, but it was so often the best that I found. All those extraordinary people. Writing this book let me describe them and what they were living through in the full rich detail I had longed for – to go beyond the confines of newspaper word-counts and the blunt facts of two-minute radio reports.

I wanted to bring everyone with me, into these flats and bunkers and night trains, in the little car speeding over the cratered highway past the misty forests of northeastern Ukraine and down into the big flat plain of Donetsk Oblast, with its pitheads and its conical spoil-tip mountains. I wanted everyone to fall in love with these places, like I had done. Perhaps, too, I wanted to have a kick at the stereotypes associated with Ukraine – grey, wartorn, ‘post-Soviet’ – and show instead how absurdly varied and rich this huge country is; how each Ukrainian city is a world in itself, utterly different to the next; how the layered and contested history is woven into the architecture and into the stories people tell about themselves. I think this is how we understand a big, complex thing like a war – through...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 8pp b/w plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Zeitgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Sprachwissenschaft | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien ► Buchhandel / Bibliothekswesen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien ► Journalistik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Europäische / Internationale Politik | |

| Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Wirtschaftsinformatik | |

| Schlagworte | Angus Bancroft • ATACMS • award-winning author • BBC radio • bbc radio 4 • BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week • book of the week • Civilians • conflict • Dani Garavelli • David Patrikarakos • Fergal Keane • First Book of the Year • firsthand account • Geopolitics • Independent Reporting • Invasion • Invasion Luke Harding • James Rodgers • Janine di Giovanni • jon lee anderson • Kharkiv • Kiev • Kursk • Kursk Offensive • modern warfare • Moscow • NATO • Neal Ascherson • Neil Ascherson • Odessa • overreach • Overreach Owen Matthews • Paraic O'Brien • people at war • Peter Geoghegan • Peter Ross • Putin • Quentin Somerville • Quentin Sommerville • Refugees • Romania • Russia • Russian politics • Saltire Society • Saltire Society First Book of the Year • Stormshadow • true accounts • True stories • true war stories • Ukraine • ukraine russia war • UN • United Nations • Vivid Reporting • Vladamir Putin • Wagner • war • War reporting • World Politics • Zelensky |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-638-4 / 1788856384 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-638-6 / 9781788856386 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich