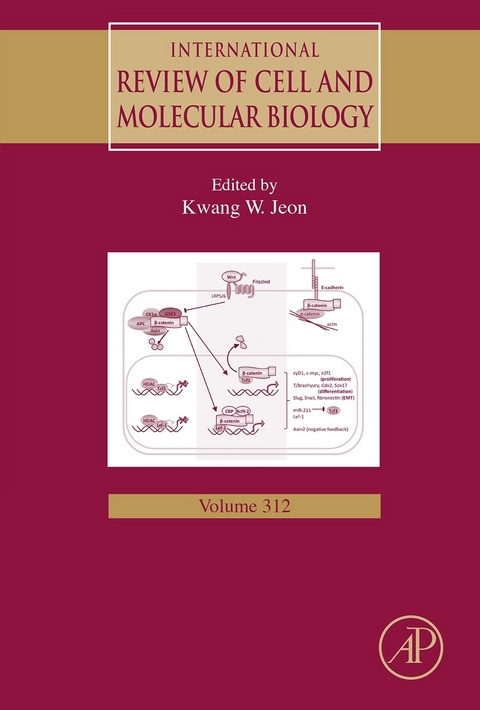

International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology presents comprehensive reviews and current advances in cell and molecular biology. Articles address structure and control of gene expression, nucleocytoplasmic interactions, control of cell development and differentiation, and cell transformation and growth.

The series has a world-wide readership, maintaining a high standard by publishing invited articles on important and timely topics authored by prominent cell and molecular biologists.

- Authored by some of the foremost scientists in the field

- Provides comprehensive reviews and current advances

- Wide range of perspectives on specific subjects

- Valuable reference material for advanced undergraduates, graduate students and professional scientists

International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology presents comprehensive reviews and current advances in cell and molecular biology. Articles address structure and control of gene expression, nucleocytoplasmic interactions, control of cell development and differentiation, and cell transformation and growth. The series has a world-wide readership, maintaining a high standard by publishing invited articles on important and timely topics authored by prominent cell and molecular biologists. Authored by some of the foremost scientists in the field Provides comprehensive reviews and current advances Wide range of perspectives on specific subjects Valuable reference material for advanced undergraduates, graduate students and professional scientists

Front Cover 1

International Review Ofcell and Molecularbiology 4

Copyright 5

Contents 6

Contributors 10

Chapter One: Microtubule Organization and Microtubule-Associated Proteins in Plant Cells 12

1. Introduction 13

2. Overview of MT Arrays and Functions in Plant Cells 13

2.1. Cortical MTs 13

2.1.1. Functions of cortical MTs in cellular morphogenesis 15

2.1.2. Function of cortical MTs on organelle tethering and transport 19

2.2. Preprophase band 20

2.3. Mitotic spindle 21

2.4. Phragmoplast 23

3. MT-Associated Proteins in Arabidopsis 25

3.1. Definition and classification of MAPs 25

3.2. Conserved MAPs in eukaryotes 26

3.2.1. .-Tubulin complex 26

3.2.2. Augmin complex 28

3.2.3. Katanin 28

3.2.4. Kinesin 29

3.2.5. EB1 32

3.2.6. CLASP (TOG domain) 32

3.2.7. MOR1 (MAP215 family, TOG domain) 33

3.2.8. MAP65 34

3.2.9. TPX2 36

3.2.10. Formin family 36

3.3. Plant-specific MAPs 37

3.3.1. Cellulose synthase interacting 37

3.3.2. SPR2 (TOG domain) 39

3.3.3. MAP70 40

3.3.4. AIR9 40

3.3.5. WVD2/WDL 40

3.3.6. RIP/MIDD family 41

3.3.7. RUNKEL (HEAT repeat) 42

3.3.8. MPB2C 42

3.3.9. SPR1 42

3.3.10. MAP18/PCaP family 43

3.3.11. EDE1 44

3.3.12. MAP190 44

4. Conclusions and Future Directions 44

Acknowledgment 45

References 45

Chapter Two: ß-Catenin in Pluripotency: Adhering to Self-Renewal or Wnting to Differentiate? 64

1. Introduction 65

2. ß-Catenin in Canonical Wnt Signaling and Adhesion 66

2.1. ß-Catenin as transcriptional coactivator and mediator of adhesion 66

2.2. Regulation of ß-catenin adhesion and nuclear activities 68

3. ß-Catenin Activities in Regulation of Pluripotency 70

3.1. ß-Catenin and its partners for adhesion in pluripotency 70

3.2. ß-Catenin nuclear activities in regulation of pluripotency 73

3.2.1. ß-Catenin and Tcfs interactions in ESCs self-renewal 73

3.2.2. Key self-renewal regulators as nuclear partners of ß-catenin 76

3.2.3. ß-Catenin nuclear activities in differentiation induction 79

4. Conclusion 82

Acknowledgments 83

References 83

Chapter Three: Recent Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology of Testicular Germ-Cell Tumors 90

1. Introduction 91

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors 91

3. Histopathology 92

4. Prognostic and Diagnostic Markers 95

4.1. Serum tumor markers in TGCTs 95

4.2. Newly discovered biomarkers detected by immunohistochemistry in TGCT subtypes 96

5. Therapy 101

5.1. Aurora-kinase inhibitors 101

5.2. Tyrosine-kinase inhibitors 102

5.3. Angiogenesis inhibitors 105

6. MicroRNAs in TGCTs 106

7. Conclusions and Perspectives 107

References 107

Chapter Four: New Insight into the Origin of IgG-Bearing Cells in the Bursa of Fabricius 112

1. Introduction 113

2. Structural Organization and Functions of the Bursa of Fabricius 114

2.1. Anatomy and histology of the bursa of Fabricius 114

2.2. Ontogeny of the bursa of Fabricius 114

2.3. Functions of the bursa of Fabricius 117

2.3.1. Major site for B-cell development 117

2.3.2. Major site for B-cell diversification 117

2.3.3. Major trapping site for environmental antigens 118

3. IgG-Bearing Cells in the Bursa of Fabricius 120

3.1. IgG-containing cells in the bursa of Fabricius 120

3.1.1. Ontogeny of IgG-containing cells 121

3.1.2. Ag-dependent development of IgG-containing cells 125

3.1.3. Absence of IgG biosynthesis by IgG-containing cells 125

3.1.4. Role of MIgG in the development of IgG-containing cells in the medulla of bursal follicles 127

3.1.5. Morphological characteristics of IgG-containing cells in the medulla of bursal follicles 130

3.1.6. Functions of IgG-containing cells in the medulla of bursal follicles 132

3.2. IgG+ B cells in the bursa of Fabricius 133

3.2.1. Ontogeny of IgM+IgG+ B cells 133

3.2.2. Ag-dependent development of IgM+IgG+ B cells 134

3.2.3. Absence of IgG biosynthesis by IgM+IgG+ B cells 136

3.2.4. Role of MIgG in the development of IgM+IgG+ B cells 137

3.2.5. Changes of bursal microenvironment after hatching 137

3.2.6. Functions of IgM+IgG+ B cells 139

4. Concluding Remarks 140

Acknowledgments 143

References 144

Chapter Five: Biological Mechanisms Determining the Success of RNA Interference in Insects 150

1. Introduction 151

2. RNAi Pathway and Small dsRNAs 152

3. Biological Functions of smRNAs in Insects 153

3.1. Antiviral role of siRNAs 153

3.2. miRNA pathway regulates different physiological processes in insects 154

3.3. piRNAs in controlling mobile genetic elements in insects 155

4. Dcr and Ago Proteins 155

5. Systemic RNAi 158

5.1. dsRNA-uptake mechanisms 159

5.2. Amplification of the RNAi signal 160

6. Species and Tissue Dependency of RNAi in Insects 161

7. RNAi as a Tool to Study and Control Insect Populations 162

7.1. RNAi in insect pest management 163

7.2. RNAi-based control of viral spread 164

8. Regulation of sysRNAi in Insects: Lessons Learned from Locusts 165

8.1. Sensitive sysRNAi responses of locusts 165

8.2. Tissue dependence of sysRNAi in locusts 167

8.3. Insensitivity of locusts to orally delivered dsRNA 167

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives 168

References 170

Chapter Six: Canonical and Noncanonical Roles of Par-1/MARK Kinases in Cell Migration 180

1. Introduction 181

2. Canonical Roles of Par-1/MARK in Cell Migration I: MTs 182

2.1. Par-1/MARK proteins 182

2.2. Regulation of MTs by Par-1/MARK 184

2.3. MT dynamics in directed cell migration 185

2.4. Par-1/MARK, MTs, and cell migration 187

2.4.1. Nonneuronal cell migration 187

2.4.2. Neuronal cell migration 188

3. Canonical Roles of Par-1/MARK in Cell Migration II: Cell Polarity 190

3.1. Cell polarity proteins in cell migration 190

3.2. Cell polarity and Par-1/MARK regulation of Drosophila border cell migration 191

3.2.1. Cell polarity and the border cell model of collective migration 191

3.2.2. Role of Par-1 in border cell migration and polarity 194

3.3. Par-1/MARK and regulation of directional protrusions in migrating cells 195

4. Noncanonical Roles of Par-1/MARK in Cell Migration 197

4.1. Wnt pathways, Par-1/MARK, and cell movement during development 197

4.2. Par-1/MARK regulation of myosin during collective border cell migration 199

4.3. Role of Par-1/MARK in H. pylori CagA-dependent cell migration 201

5. Concluding Remarks 202

Acknowledgments 203

References 203

Chapter Seven: Insights into the Mechanism for Dictating Polarity in Migrating T-Cells 212

1. Introduction 213

2. G-Protein-Coupled Receptors 217

3. Adhesion Receptors and Associated Proteins 219

3.1. Integrins (LFA-1) 219

3.2. Rap1/RAPL/Mst1 221

3.3. Talin-1, kindlin-3 222

3.4. a-Actinin 223

3.5. SHARPIN 223

4. Membrane Recycling/Organelles 224

5. Signaling Molecules 226

5.1. Rho-family GTPases 226

5.1.1. Rho/Rho-kinase 227

5.1.2. Rac 230

5.1.3. Cdc42 232

5.2. PIP-2/PIP5K 233

5.3. Phospholipase C 236

5.4. Calcium 237

5.5. PIP-3, PI 3-kinase 238

5.6. Janus kinases 240

5.7. PKC isoforms 241

5.8. ERK/MAPK 242

6. Cytoskeleton 243

6.1. Microtubules 244

6.2. Actin 246

6.2.1. Formins 247

6.2.2. WASP, N-WASP, WAVE, WIP, Arp2/3 248

6.2.3. Coronin-1 249

6.2.4. Ezrin/radixin/moesin 250

6.2.5. Myosin II 253

6.2.6. L-plastin 255

6.2.7. Cofilin 256

6.3. Septins 257

7. Polarity Proteins 258

7.1. Scribble/Dlg 259

7.2. Rap1 and the Par complexes 259

8. Membrane Microdomains (Rafts) 260

8.1. Gangliosides 262

8.2. Flotillins 263

9. Self-Organizing Aspects of T-Cell Polarity 265

10. Concluding Remarks 267

Acknowledgments 269

References 269

Index 282

Color Plate 289

Microtubule Organization and Microtubule-Associated Proteins in Plant Cells

Takahiro Hamada1 Department of Life Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

1 Corresponding author: email address: hama.micro@bio.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Abstract

Plants have unique microtubule (MT) arrays, cortical MTs, preprophase band, mitotic spindle, and phragmoplast, in the processes of evolution. These MT arrays control the directions of cell division and expansion especially in plants and are essential for plant morphogenesis and developments. Organizations and functions of these MT arrays are accomplished by diverse MT-associated proteins (MAPs). This review introduces 10 of conserved MAPs in eukaryote such as γ-TuC, augmin, katanin, kinesin, EB1, CLASP, MOR1/MAP215, MAP65, TPX2, formin, and several plant-specific MAPs such as CSI1, SPR2, MAP70, WVD2/WDL, RIP/MIDD, SPR1, MAP18/PCaP, EDE1, and MAP190. Most of the studies cited in this review have been analyzed in the particular model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. The significant knowledge of A. thaliana is the important established base to understand MT organizations and functions in plants.

Keywords

Plants

MAPs

Microtubule

Cortical microtubules

Preprophase band

Mitotic spindle

Phragmoplast

Arabidopsis thaliana

1 Introduction

Animals and plants have lots of differences. At the cellular level, cell motility is one of the prominent differences. For example, animal cells move independently and occupy specific positions during embryogenesis. In contrast, plant cells remain in place during embryogenesis, being confined by their cell wall. To accomplish morphogenesis and developments, plants control the directions of cell division in principle. Because the relative positions of cells never change after cell division, differentiation relies on cell-autonomous programs and strong-signaling cues between cells. In parallel, plant cells start expansion to proper sizes and shapes. Plant microtubules (MTs) and MT-associated proteins (MAPs) regulate both cell division and expansion. To enact morphogenesis, plants have evolved plant-specific MT arrays. Here, I review the properties and functions of MAPs that have been characterized in plants. I organize the review in two sections: MT arrays (Section 2) and MAPs (Section 3).

2 Overview of MT Arrays and Functions in Plant Cells

Plant cells have four prominent MT arrays: cortical MTs, preprophase band (PPB), mitotic spindle, and phragmoplast (Fig. 1.1). Briefly, cortical MTs regulate the direction of cell expansion and the other three MT arrays mediate cell division including the specification of its orientation. Organization and function of these MT arrays are described here.

2.1 Cortical MTs

Plant cells usually have a large vacuole at the center and thin layer of cytoplasm at the periphery. In peripheral cytoplasm, many dynamic MTs localize immediately adjacent to the plasma membrane forming an almost two-dimensional cortical array called “cortical MTs” (i.e., in the cell cortex). Using live cell imaging methods, cortical MTs are readily observed and their behavior has been well characterized. The dynamics described below has been examined mainly at the hypocotyl epidermal cells of Arabidopsis thaliana but with support from other cell types, species, and other mitotic MT arrays and is taken as generally true for plants.

In cells, MT nucleation (i.e., the initiation of polymerization) occurs at the site of γ-tubulin complex. In animal cells, many of these complexes are packed into foci called “MT-organizing centers” (e.g., the centrosome), but in plant cells, the complexes are dispersed throughout the cell. Often, a complex binds to the side of an extant MT, but sometimes a complex binds to an as-yet-undefined site in the cortex. From the side of an extant MT, a nucleated MT elongates either at an angle around 30° (Murata et al., 2005), thereby forming a branch, or parallel to the extant one, thereby forming a bundle (Chan et al., 2009). Similar to the cytoplasmic MTs of animal cells, cortical MTs in plants exhibit dynamic instability, with repeating phases of polymerization (i.e., growth) and disassembly (i.e., shrinkage) separated by pauses, catastrophes, and rescues. A catastrophe defines the sudden change from growth to shrinkage and a rescue defines the reverse. In addition to these dynamics, MT severing is occasionally observed. Growing MTs often encounter another MT at the virtual two-dimensional cortical array. The consequences of the encounter include bundling, catastrophe, or crossing. The choice among these behaviors depends on a considerable extent on the angle between them. Bundling is favored for angles of 30° and less, whereas catastrophe and crossing predominate for larger angles (Dixit and Cyr, 2004). The bundling mechanism is well adapted to “search and capture model,” which MTs repeat growth and shrinkage phases until reaching a given target.

Although the MT itself has intrinsic dynamic instability and nucleation ability, MTs in cells are regulated by hundreds of MAPs, enriching the scope of MT behavior. In principle, some molecules should be bound tightly to the plasma membrane. This binding might be mediated by several candidates, including CSI1, CLASP, and PLD (Ambrose and Wasteneys, 2008; Gardiner et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2010). To regulate MT dynamic instability, relevant candidates include TOG domain-containing proteins such as MOR1, SPR2 (SPIRAL2), and CLASP. Both MOR1 and SPR2 stimulate MT dynamics directly, as confirmed in vivo and in vitro (Hamada et al., 2009; Kawamura and Wasteneys, 2008; Yao et al., 2008). CLASP has multiple functions for the cortical array, both increasing cortical MT attachment to the membrane and stabilizing cortical MTs’ cell edges (Ambrose and Wasteneys, 2008; Ambrose et al., 2011). MAP65 and WVD2 (Wave-Dampened 2)/WDL (WVD2-like) families are characterized as MT-bundling factors (Jiang and Sonobe, 1993; Perrin et al., 2007). The mutants of MOR1, SPR2, CLASP, γ-tubulin complex, and katanin complex have twisting macroscopic phenotypes that caused by the change of MT array orientation from transverse to oblique in young elongating cells. Similar phenotypes are often observed in mutants of other MAPs, such as EB1, MAP70, and WVD2/WDL (Bisgrove et al., 2008; Korolev et al., 2007; Yuen et al., 2003), indicating that these MAPs are involved in cortical MT organization to keep specific cell-wide orientation, such as transverse to the long axis of the organ.

2.1.1 Functions of cortical MTs in cellular morphogenesis

Plant cells have two types of growth: “diffuse growth,” which occurs in most cell types, and “tip growth,” which occurs in specialized cell types such as pollen tubes and root hairs. Although semirigid cell walls surround plant cells, outward high turgor pressure enlarges by deforming relatively extensible regions of their cell wall.

In the case of tip growth, expansion is confined to the cell tip, which has a sufficiently extensible cell wall to deform under turgor pressure. In contrast, with diffuse growth, expansion takes place over the entire surface of the cell, or majority thereof. Diffuse growth is typically anisotropic. Expansion rate between maximal and minimal directions often exceeds an order of magnitude or even more. For this type of growth, cortical MTs play a prominent role in determining the direction of expansion.

The anisotropic nature of diffuse growth depends to a large extent on the orientation of cellulose microfibrils. When microfibrils align in one direction within the cell wall, encircling a cell like a hoop, the cell expands perpendicular to the net orientation of the microfibrils (Fig. 1.2A). When the direction of cellulose microfibrils is random, the cell expands isotropically, eventually becoming spherical (Fig. 1.2B). To shape long extended cells like typical root and hypocotyl plant cells, cellulose microfibrils are located transversely against the longitudinal direction of expansion.

The relationship between cellulose microfibrils and MTs was first recognized in the early 1960s, both from the spherical cells that result when elongating Nitella axillaris internode cells is exposed to the MT inhibitor colchicine (known then as a spindle fiber-disorganizing agent) (Green, 1962), and from the parallel alignments of cellulose...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.10.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Genetik / Molekularbiologie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zellbiologie | |

| Technik | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-12-800444-4 / 0128004444 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-12-800444-9 / 9780128004449 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,5 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: PDF (Portable Document Format)

Mit einem festen Seitenlayout eignet sich die PDF besonders für Fachbücher mit Spalten, Tabellen und Abbildungen. Eine PDF kann auf fast allen Geräten angezeigt werden, ist aber für kleine Displays (Smartphone, eReader) nur eingeschränkt geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Größe: 10,3 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich