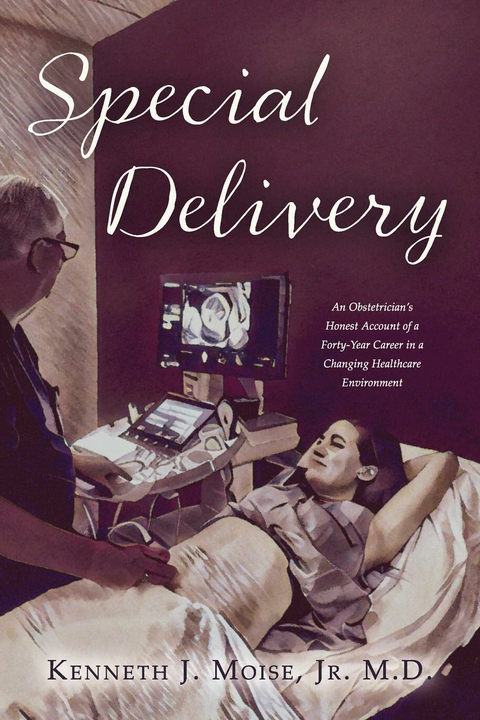

Special Delivery (eBook)

384 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-8989-4 (ISBN)

The book is filled with patient anecdotes that expose the reader to the joys and sorrows of pregnancy and childbirth. The author uses these anecdotes as a platform to educate the reader about the many poorly understood aspects of academic medicine as well as medicine in general. Although there are many current books on the market that are medical memoirs of physician experiences, Special Delivery is unique in chronicling the development of a medical career from a student's struggles with pre-med college courses to achievement of tenure as a full professor at a major medical school. The author's challenges with his own diagnosis of a rare autoimmune disease and his wife's subsequent diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma introduce a new perspective from the "e;other side of the bed"e; on the problems with healthcare in our country.

1

Prologue

The little black box on my belt squealed with an ear-piercing sound—“beep, beep, beep.” I looked down at its LED display—my secretary paging me. I grabbed the desk phone nearby and called my office. “There is a patient on the phone from Florida that would like to talk with you,” she said.

“Ok, can you go ahead and connect me,” I responded.

“Dr. Moise, I know you are busy but could I talk with you about my high-risk pregnancy?” came the voice over the line.

“Sure, go ahead,” I responded.

“My name is Kathy and I want to see if you will take care of me. I been looking up medical articles in the library and I think you are considered an expert on the condition I have,” she said.

“Tell me your story,” I replied. Kathy’s blood type was Rh negative. In her first pregnancy, she had delivered a little girl, but at the time of the delivery, her obstetrician determined that she had Rh antibodies in her bloodstream. The usual injection given to most Rh-negative patients to prevent these antibodies from forming would no longer work. In her next pregnancy, Kathy’s antibody titer (a measure of the amount of antibody in her bloodstream) turned out to be very high. But unfortunately, her doctor did not follow her pregnancy that closely.

“One day at around six months into my pregnancy, my baby boy stopped moving,” she told me. “I called my Ob’s office and they told me to come in right away. I watched anxiously as the technician poured gel on my belly and placed the ultrasound probe to find my baby’s heartbeat. She searched in vain for several minutes. Then she informed me that she needed to get the doctor. Several anxious minutes went by. I just knew something was wrong. My Ob doc came into the room. Without saying a word, he placed the ultrasound on my pregnant belly and again began to look around. After a few moments he confirmed by biggest fear – my baby boy’s heart had stopped.”

Kathy went on with her story, “They sent me to the emergency room. After about two hours of waiting in the exam room, an emergency room doctor came in. He did another ultrasound to confirm there was no heartbeat. He then called the on-call obstetrician who told him I should see my primary OB in the morning. By this time my husband had arrived and he was getting angry. We decided to drive to another hospital ER but the answers there were the same – the ER could do nothing and the on-call OB did not want to take care of me.”

Kathy paused for a moment on the phone call to collect her thoughts, “Just before I was discharged for the second time, a nurse came by and told me she had called one of the OB physicians she knew. She told me that he would take care of me. We began the induction of labor later that night. Our little boy was born six hours later. I gazed at him and noted how perfect and peaceful he looked wrapped in this blue birthing blanket. We decided to name him Hope.”

Hemolytic disease of the fetus/newborn is the result of a difference in blood types between a pregnant woman (who is Rh negative) and her unborn child (who is Rh positive due to genes inherited from its father). In some situations, red blood cells from the fetus escape into the woman’s blood stream, are recognized as foreign to her and antibodies are formed. In most cases, this immune reaction can be prevented by giving the Rh-negative pregnant patient a special injection (called Rhesus immune globulin) in the seventh month of pregnancy and again at the time of delivery. But sometimes this fails, and Rh antibodies form in the patient. If she carries a Rh-positive fetus in her next pregnancy, the antibodies can cross through the placenta and attack the fetal red blood cells. This can then cause severe anemia (low blood count) in the fetus and even death. This is called hemolytic disease of the fetus/newborn.

“I’m now eight weeks pregnant, Dr. Moise,” Kathy said. “I am so scared. Could this happen to me again? I can’t go through losing another baby.”

“I understand, Kathy,” I responded. “Let’s see what we can do. I want you to see Dr. Schneider, a Maternal-Fetal Medicine specialist (a board-certified subspecialist in high-risk obstetrics), who has an office near where you live. He will do ultrasounds every week and if he thinks the baby is getting into trouble, he will refer you to me if you need special treatments.”

Six months into the pregnancy, Kathy called back. Through tears, she told me, “They say my baby has hydrops and could die any day. This can’t be happening!”

“I want you to catch the next flight here,” I told her. Kathy arrived the next morning and an ultrasound indeed revealed that her unborn daughter was near death due to severe anemia. Later that same afternoon, we performed an emergency intrauterine transfusion—we used ultrasound to guide a needle into the fetal umbilical cord and give life-saving Rh-negative red blood cells.

The following day, the baby’s condition showed marked improved on the ultrasound. Thanksgiving was two days away. Kathy was a fireman in Florida and a one-way return plane ticket before the upcoming holiday was more than she could afford. Karen, my wife, was one of our nurse coordinators at our Fetal Center. She called the local Ronald McDonald House. Pretty much every pediatric hospital in our country has one of these special temporary residences for families with sick pediatric patients.

“I know this is unusual, but I have a pregnant woman with a very sick baby on board that has come all the way from Florida for treatment,” Karen said. “Is there any way you could bend the rules a bit and let her stay with you through Thanksgiving?” They acquiesced. But there would be no family Thanksgiving dinner for Kathy.

“You must come to our house for Thanksgiving,” Karen told her. “Ken will pick you up from the Ronald McDonald House.”

There were about fifteen folks at our dinner table for the holiday meal the next day. Dr. Stan James, my partner, happened to pull up a chair next to Kathy. “I think I’ve met you before somewhere,” he said turning to her.

“That’s right,” she replied. “I was lying on the operating room table two days ago when you were assisting Dr. Moise. I came here to give thanks for the wonderful things you’ll do.”

I have spent my entire career of four decades in academic medicine. When most patients seek medical care, they see a physician in private practice. For the most part, the mission of these physicians is to care for patients. Academic physicians are affiliated with one of the 141 accredited medical schools in the USA. Their mission is threefold: research, teaching, and clinical care. This book chronicles my journey from undergraduate education to medical school to my role as a tenured full professor at several major medical universities. In it, I attempt to educate the reader on how our medical schools improve our country’s heath care by aiding in the discovery of new treatments for disease. Academic physicians also serve to train the next generation of physicians. And then, we take care of patients. Often, this involves supervising residents in training; sometimes we care for our own patients.

Medicine is a unique profession. Because you wear a white coat or a pair of scrubs, a patient entrusts you with their innermost secrets. They put their lives (and in the case of the pregnant women I have cared for, their unborn baby’s life) in the hands of a perfect stranger after little more than a handshake greeting. It is truly a privilege to engender this degree of trust even in the most trying of times. It is not to be taken lightly.

I have seen significant changes in health care over the past four decades. Some are good and some have led to increased physician burnout and patient dissatisfaction. The careful history and physical examination were once the centerpiece of the patient interaction. The patient was asked to tell you her story in her own words followed by a physical examination–a laying of the hands to decipher any signs of disease. These steps were essential to the art of medicine. Today, however, sophisticated blood tests and advanced imaging procedures are the norm to make a diagnosis. Indeed, the art of medicine has now being replaced by the science of medicine. Patient information is now entered into the electronic medical record (EMR) on a computer screen—a further distraction from interacting directly with our patients.

Academic medicine has changed too. Shrinking monies in health care have led many medical schools to have their faculty focus on clinical productivity often to the detriment of clinical research and teaching. It is my sincere hope that the reader will be afforded the opportunity to follow my journey from first learning to do clinical research to later mentoring physician trainees. Insights into the politics of medicine are divulged through my roles at multiple academic institutions where I have worked in my career.

Physicians learn their trade through patient experience. Throughout the book, I have chosen to recount some of the patient anecdotes that remain permanently etched in my memory. The names of the patients and the physicians have been changed to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Gynäkologie / Geburtshilfe |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-8989-3 / 1667889893 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-8989-4 / 9781667889894 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,1 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich