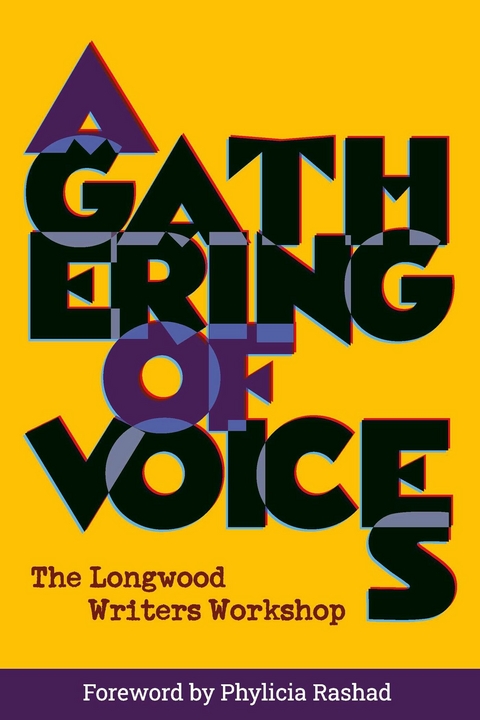

Gathering of Voices (eBook)

312 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-7183-5 (ISBN)

Hattie Winston, acclaimed actress, singer, producer, director and Broadway veteran continues to entertain audiences on film, stage and television, in a career that has spanned more than five decades. Currently Ms. Winston can be seen as Sister Pearlie, opposite Cedric the Entertainer and Niecy Nash in The Soul Man on BET. She is, perhaps, best known for her performance as Margaret on the hit CBS series Becker, where she starred with Ted Danson for six seasons. Some of her other TV credits include The Electric Company, Homefront, Castle, Girlfriends, ER, The Game, Scrubs, Reed Between the Lines, Cold Case, Mike and Molly and many more. Ms. Winston was a founding member of The Negro Ensemble Company in New York City and has acted both on and off-Broadway; The Tap Dance Kid, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Vagina Monologues, Scapino, Up the Mountain, Love, Loss and What I Wore are a few of the shows she has appeared in. She has strutted her stuff in Quintin Tarrantino's Jackie Brown and sparred with Clint Eastwood in his True Crime. Ms. Winston is wife of Harold Wheeler and mother of Samantha Wheeler, her proudest roles. Ms. Winston's memoir will be published in 2024.

A moving Anthology containing a varied collection of personal, vibrant,introspective, and lyrical stories from a diverse and seasoned group ofsix dedicated writers. Their storytelling unfolds with grace, humor, anduniversal truths. These stories resonate with memories of struggles they've waged, of battles they've won and lost, and of their manyexperiences that illuminate their mature wisdom and their hard-wonresilience. The compelling narratives in this book speak to all ages of readers who are looking for confirmation that the challenges and adversity presentedby life's struggles can be overcome with hard work, a never-ending belief in oneself and the willingness to persevere through every hardship.

Chapter 1:

Battlefield

By Hattie Winston

As the hours passed and the faces changed on my bus ride, nothing really mattered, because I was going to visit my Daddy Louis at his new home, in this faraway land called Memphis, Tennessee. Even today, I imagine all those trees that were felled during the 1950s, touched by my Daddy Louis all those years ago and fashioned into lumber, made their way into the eaves, walls, foundations and furniture of the homes and churches of today. I have a special affinity for trees, all trees. They remind me of my Daddy, now constantly on my mind.

Daddy walked with a limp, but to me he was the tallest man in the world! He was like fine-grained mahogany, a deep reddish brown, with African onyx peeking through his taut skin. He was not a tall man. He was not a big man. But he was an imposing man. His head was always held high, his back erect; he was soft-spoken, with a quiet dignity. Even with his cane, he had the gait of a panther and a “loud” in his silence that caused men, whether Black or white, to respect and fear him at the same time. I was his Tee. His dream.

“My Tee will touch the sky.” That’s what he used to say. That was his dream for me. I wondered if I had made him proud. I had dared to reach from the red clay of Mississippi and the sawdust of Tennessee to a Broadway stage. I was certainly not the first to do so, but I was the first in our family. Mama Birtha washed white folks’ clothes. Daddy Louis stacked lumber. Their labor sent me to school. Their unconditional love saw me through. On the wings of their prayers, I was propelled through stumbling blocks and nonbelievers.

I remember Daddy Louis’s hair as always neat. Although a luxury, his visits to the barber were regular. He insisted on creases in his khaki work pants. Said you have to pay attention to the way you look, because other people do. I can hear him now, “Baby, you going out the house with your hair looking like that?”

“What, Daddy?”

“Maybe you should go in your room and put a brush to your edges. What ya think?” That was his way of saying, “Go brush your hair.”

“Yes, Daddy.”

It didn’t matter that I was just going outside to play!

It seemed to me his Greenville body was different from his Memphis one. In Greenville he would put his feet up, let out a loud, mouth-wide-open, free-flying laugh. In Memphis his laughs were small and squeezed. His shoulders were never relaxed. Memphis Louis was always on guard.

But he was my conquering hero. His conquests were not knights in shining armor or neighboring nations or the hooded hoodlums of the Klu Klux Klan. Rather, he battled the searing breath of segregation from mindless bus drivers to department store clerks as the hooves of racism beat down on the bended backs of hard-working daddies trying to provide for their families. When Daddy Louis’s job forced him to move to Memphis, things changed. Mama Birtha and I still lived in Greenville, Mississippi, but Daddy now lived in Memphis, Tennessee. I asked him once why he had to stay in Memphis and not with us. He put down his cane, sat and pulled me onto his lap. He didn’t speak for a while, just gently patted me on my back.

Finally, he said, “I don’t want to live in Memphis, baby. I don’t want to be away from you and your mama, but now that my job has moved to Memphis, it’s better for us if I’m there. I make a little more money and your mama doesn’t have to kill herself in other people’s houses. I don’t want her working that hard.”

“I could get a job, Daddy.”

Daddy let out his Greenville laugh. Filled the whole front room.

“Thank you, baby, but all I want you to do is get good grades at Sacred Heart School. You keep up your grades, I’ll keep working so I can pay your tuition.” Sometimes a ‘dream’ could be hard on everybody.

I missed my Daddy. When Woods Lumber Company first relocated to Memphis, Daddy would come home every weekend. He would catch the Greyhound bus and ride for hours to be with us. I always tried to stay up to meet him at the front door, but I never made it. Sleep always took over. But when I smelled bacon frying, fresh coffee and apples with nutmeg and cinnamon, I knew Daddy was home. We could always taste Mama Birtha’s love for us in her cooking. Daddy showed us his love through his blistered hands and throbbing feet.

Our weekends together were special. We would have Mama Birtha’s “Almost-like-Christmas” cooking on an ordinary weekend: Chicken stuffed with cornbread dressing, a Cornbread Cooler (crushed cornbread with a little sugar, in a glass of cold buttermilk, served with a spoon, one of Daddy Louis’s favorites), fresh greens from our garden, creamed corn, cabbage with onions, and blackberry cobbler. All weekend, yeast rolls would rise in the kitchen, smelling like heavenly angels had come down to knead the dough, filling the house with aromas of “I’ve been saved, sanctified, and filled with the Holy Ghost.” Old friends stopped by Hyman Street to visit. Laughter. Lots of laughter. When Daddy was home, there was always music. Howling Wolf and Mahalia Jackson competed for a spin on our record player. After everyone left, Daddy, Mama Birtha and I would sit around in the front room and talk about our week. Daddy Louis usually told stories about his boss, “ol’ man Pruitt.” Mama complained about how disrespectful the Gamble kids were getting and how much food they wasted. My tales were mostly about school.

“All right, baby, any tests this week?”

“We had an arithmetic test. It was easy. I got 98.”

“If it was so easy, why didn’t you get a hundred?” he teased.

“Oh Daddy...We also had geography and all the state capitals. I got most of them. It was a practice test, so any I got wrong, I can study and be ready for the real test. Catechism was a breeze this week.”

“What do you mean, a breeze?” Mama Birtha chimed in.

“It was all about the ten commandments. We had to recite all of them. Simple as ABC.”

“What’s the fourth commandment?” they both blurted at the same time.

“Honor thy father and thy mother. God. Of course, I know that!”

“I think you just broke the second commandment, Thou shall not take the Lord’s name in vain,” declared Mama Birtha.

They both burst out laughing. A ‘dream’ was expected to be among those at the head of the class. Usually, I didn’t disappoint.

Sunday evening always came too soon. Sunday evening meant goodbyes and tears. My Daddy Louis would be back on the Greyhound line, headed to his little gray house on the lumberyard. He not only worked on the yard, he lived there too. This was part of the agreement he made with the Pruitts, who owned Woods Lumber Company. Live on the yard. Keep his eyes open all the time. No rent. The house was a small, dreary one-room living space, with an outer common room for anyone else who happened to be on the lumberyard. His house wasn’t really a home. It was just a temporary-away-from-us-place to lay his head.

On his many trips between Greenville and Memphis, Daddy Louis always spoke to the white bus driver.

“Evening, sir.”

He said he rarely got an “Evening” back, but he did it anyway. Said it threw the driver off guard. Once he’d reached the back of the bus, “Evening” was always returned. Sometimes hats were tipped. Heads nodded. Traveling shoeboxes with delightful treats always greeted him. Southern aromas and smiles danced across the aisle. Pretty ladies looked pretty-as-a-picture in their best dresses. Sometimes Mama Birtha got a little jealous when he talked about all the pretty ladies. Daddy Louis always said, “Hell, Birtha, I ain’t dead. I can STILL look at women.”

On his many trips, Daddy Louis mostly watched the kudzu vines growing along the highways. Kudzu, “the vine that ate the South,” grew and multiplied, covering everything it contacted. This creeping, flowery, grape-smelling vine overtook trees, telephone poles, cars and even houses. As the kudzu grew, becoming heavier and heavier, so did Daddy Louis’s fatigue. His body began to rebel against those frequent Greyhound trips. He was foreman of the yard, in charge of all workers, both Negroes and whites. This was unprecedented in the 1950’s, and the stress of maintaining peace on the lumberyard, in segregated Tennessee, was taking its toll. Even nights when only he and the night watchman were on the yard, no peace was to be found. Holding his tongue, when he wanted to lash out, when some disgruntled white worker called him or another Negro worker “nigger,” or a Negro worker disrespected him because he was the boss, or one of the Pruitts raised his voice when speaking to him. All these things, plus all the traveling back and forth, was eating him up inside. His heart longed for us; his body wanted rest. Back and forth he rode. Back and forth. Across state lines. The kudzu grew higher and wider. Daddy Louis’s weariness grew bigger.

His weekly trips were wearing him down. His work began to suffer....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-7183-5 / 9798350971835 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,6 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich