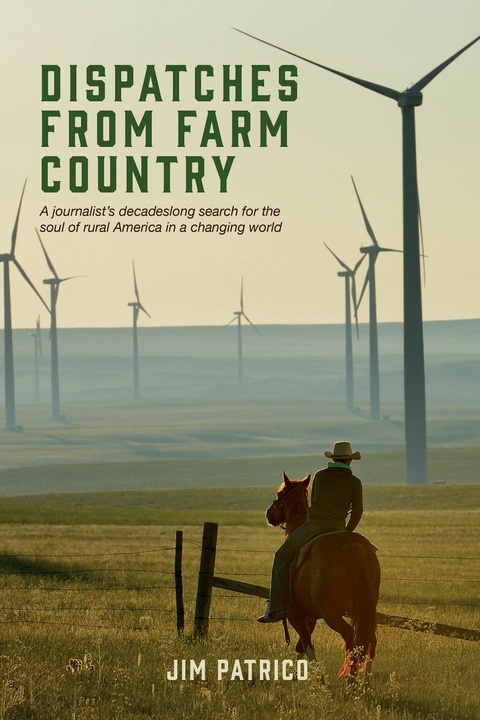

Dispatches From Farm Country (eBook)

388 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-7162-0 (ISBN)

Jim Patrico, a seasoned photojournalist, has spent more than 40 years traveling across America and 21 other countries to document the lives of farmers and ranchers. Originally from a large city, he embedded himself in rural life by moving to the small farming town of Plattsburg, Missouri. Patrico's unique perspective and dedication earned him numerous accolades, including the Henry R. Luce Special Citation for public service reporting, the title of Agricultural Journalist of the Year by the North American Agricultural Journalist, and two Oscars in Agriculture. As a Master Writer and Writer of Merit for the American Agricultural Editors Association, his work has had a significant impact on agricultural journalism. Patrico is a graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism with an emphasis on photojournalism. He is also the author of two commissioned books, one about the American tax system and another on the history of photo use by farm magazines. His extensive career highlights his deep connection to and appreciation for rural America.

A widening gap between urban and rural cultures has left America divided and bewildered. Fortunately, photojournalist Jim Patrico has spent more than 40 years exploring the rural side of that gap. The result is "e;Dispatches from Farm Country,"e; an insightful and often humorous recounting of a journalist's travels through rural communities. Chapter by chapter, Patrico focuses on real farmers and ranchers: a California dairy farmer who fosters babies born in prison because she can't stand the thought of little ones suffering for their mothers' bad decisions; the owners of the two oldest farms in America who feel the presence of their ancestors walking their fields; a farmer whose fall from a barn roof led his family to add farm-brewed beer business; the fifth-generation Black farmer whose family still contends with racism; the Kansas ranch couple whose love blossomed when he braved a 1930s blizzard on horseback to visit her for Valentine's Day; and an Appalachian farmer whose neighbors deal drugs and fly a Confederate flag in their front yard. "e;Dispatches from Farm Country"e; tells intimate stories that enchant and inform. They give the reader a better understanding of rural America and help bridge the gaps between cities and small towns.

Chapter 1

Roots

My grandfather Luigi Patrico was a farmer of sorts. He emigrated from Sicily to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1901. According to family lore, in Sicily he was either a cavalryman or a jeweler. Maybe both. Depends on which of my relatives is telling the story. In any case, we agree that he eventually became a truck farmer on the outskirts of St. Louis. That made sense for an Italian immigrant. Many newly minted Americans from Italy settled in cities but were in the fruit and vegetable business across the country. It was a niche to which they gravitated in the same way many Irish immigrants became cops: They had family ties to the business.

I don’t know how long Luigi farmed or what he did after that. I only remember him as a feeble old man sitting in a wheelchair in my Aunt Mary’s tiny brick house in north St. Louis. In my memory, he has wispy white hair and a drooping white mustache. He smells of old cigar smoke and beckons me with his cupped hand. I sit on his lap, and his hoarse voice utters Italian words I never understood.

Now I like to imagine him as a young farmer and see him bent over a row of cabbages somewhere outside the city. It’s a flat field with rich black dirt, and the sky above is a blue sea with floating white clouds. At the end of the row is a “stake truck,” an ancestor of the pickup with an open flatbed and removable wooden slats that hold cargo in place. My grandfather loads a wooden wheelbarrow with crates of cabbages and pushes them slowly toward the truck. Where he goes after that I only imagine. Maybe he heads to Soulard Market, a bustling, chaotic mass of people and produce stands near downtown.

In Luigi’s day, Soulard was essential to its times. Luigi and his comrades unloaded their stake trucks into dew-damp stalls every morning (except Sunday) before the sun rose over the nearby Mississippi River. Wholesalers and retailers were waiting to buy produce in bulk to take to grocery stores. Housewives arrived soon after and squeezed tomatoes and haggled with individual vendors over prices. Space in the icebox at home was limited, so it was important for the women to choose wisely. By early afternoon, piles of fruits and vegetables had dwindled to scraps and picked-overs.

Today Soulard has a forgotten-world feel. It’s still there on the edge of downtown. But its nature has subtly changed. It still serves as a place for wholesalers to meet retailers. But it’s not a neighborhood place anymore. It has a touristy feel and thrives mainly on Saturdays. Young locals come to soak up atmosphere they can’t find in a supermarket and to select—perhaps without the expertise of their great-grandmothers—fruits and vegetables that come in crates from both far-flung fields. It’s a hip place where young adults push fancy strollers and sip lattes from recyclable paper cups while chatting with other couples out for a lark. To me, Soulard still has a lingering scent of history. When I visit, I think of Luigi.

My other grandfather, Joseph Malcolm Navin, was German/Irish and grew up in the wooded hills and rolling fields of Marion County, Missouri, 100 miles up the Mississippi River from St. Louis. Grampa’s hometown of New London is just south of Mark Twain’s Hannibal, and whenever we Patricos visited during family reunions, I thought of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. I could almost see them darting through the rough countryside on some boyhood adventure.

Our cousins who lived in that neighborhood were country folk and farmers. They dressed differently and lived differently than we urbanites/suburbanites. I remember one of our older female cousins lived in a house that still had a hand pump in the kitchen sink and an outhouse out back. The yard consisted of mostly packed dirt with chicken feathers drifting lazily in the dust and multiple dogs moseying around looking for a shady spot in which to nap. A dilapidated henhouse sat in front of a line of trees and emitted a dried manure odor. In the distance were tall cornfields and the gravel drive that had funneled us to the house.

I don’t know for a fact that Grampa ever farmed. Our family lore isn’t clear on that point. I only assume he did because his relatives did, and he wore bib overalls around the house. I do know for certain that he was a doughboy in World War I. He drove a locomotive for the Army and helped the Navy scuttle a ship from which he liberated a brass ship’s clock that now sits on my shelf. More importantly, he brought home a French bride, my Gramma, Marianne Nerrienet.

Gramma told me many years later that her German mother-in-law in Marion County was unkind to her and mocked her lack of English and her foreign way of dress. Not surprisingly, Gramma didn’t develop a love for many of her country in-laws, especially the German ones. With her French heritage, she still bore a grudge against “Les Boches” for the War to End All Wars. Soon after she arrived in Missouri, she and Grampa moved to St. Louis, where he began work as a teamster and later as a construction laborer.

Many new government buildings were going up in the 1930s because of federal spending designed to defeat the Great Depression. If you look at downtown St. Louis today, you see numerous white stone courthouses, government buildings and banks built during the period. Grampa told us once that a stone fell from one of the buildings where he was working, and it hit him in the noggin. “Good thing I had a hard head,” he joked.

I didn’t arrive until after he retired, and he and Gramma had moved from north St. Louis to a house in Black Jack, Missouri, a village northwest of downtown. Black Jack was only an intersection of three roads in those days and contained a saloon, a grocery store and a hardware store. It was as country as country could be only 20 miles from a major city. The Navins had an acre and a third of land in Black Jack, and I thought they were farmers.

Gramma, a tiny woman who wore print dresses and possessed an indomitable spirit, had a lush flower garden behind the brown brick, two-bedroom house. She tended it diligently despite a pronounced limp, which she acquired when a surgeon years previously fused the bones in her left knee—maybe by accident, maybe because that’s the way they treated knee problems back then. That impediment left her more dependent on Grampa than she’d like to be. Out in her garden, she would call him from whatever chore he was doing to pull water from the well house, which he did using a metal bucket and a chain on a wheel. He’d pour the cold water into a metal watering can for her, and she’d judiciously sprinkle it around the base of her roses and peonies.

Flowers were her joy. But they were a minor part of Gramma’s “farm” work. To the east of the house was a half-acre vegetable garden. Potatoes. Tomatoes. String beans. Cucumbers. Peppers. A small patch of asparagus grew at the edge in soil mounded with chicken manure for fertilizer. Out of this garden came mountains of food. Grampa oversaw the planting and the harvesting. But it was Gramma’s duty to make sure we could eat it at harvest time and all through the winter ahead. Canned tomato juice and string beans were her specialties, and she made ketchup, which she kept in old 7UP bottles. Gramma also put up dozens of jars of pickles from homegrown cucumbers: dill, sweet and bread-and-butter.

As harvest began on hot summer days, she and Mom would set up a canning assembly line in the brick house’s spacious kitchen. They washed tomatoes in the big porcelain sink, then parboiled them in a large pot on the gas stove. When the red-yellow skins began to crack, out the tomatoes would come to be plunged into a cold water bath. The two women in their stained aprons would then peel the skins and squeeze the juice out of the meaty tomatoes using a conical sieve and a wooden pestle. The sieve would strain the seeds and any remaining skin as Gramma and Mom mashed and twisted that wooden pin against the softened tomatoes. The juice would flow into a bowl, which they emptied through a metal funnel into mason jars.

When they had enough jars to make a batch, the women aligned them on a rack in an enormous steel pressure cooker and turned the T-clamps to seal the lid tight. They put the pressure cooker on the stove and turned on the gas burner. We kids would watch the gauge on the top of the cooker as its finger climbed the dial. “Tell us when it gets to the green zone,” Gramma instructed us. “We don’t want it to get into the red.”

“Why? What happens if it gets into the red?”

“The whole thing could explode,” she said.

That got our attention. We watched the gauge intently as tiny spirits of steam leaked from a pressure valve. Please don’t explode!

String beans came on at about the same time as tomatoes, and the kitchen hummed with activity again as Grampa dumped onto the kitchen table a bushel basket of beans we had helped picked earlier. He headed to his basement kingdom for a beer break while the rest of us sat around the round oak table and began snapping beans. It was fun at first. But we were kids and easily bored. Soon the grab-snap-grab routine got old. To keep our attention, Gramma and Mom would talk to us and to each other about anything that came to mind. Gramma was skilled at asking about what we had learned in school that year and what library books we were reading now. She’d also tell stories about Grampa and the trouble he’d gotten...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-7162-0 / 9798350971620 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,0 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich