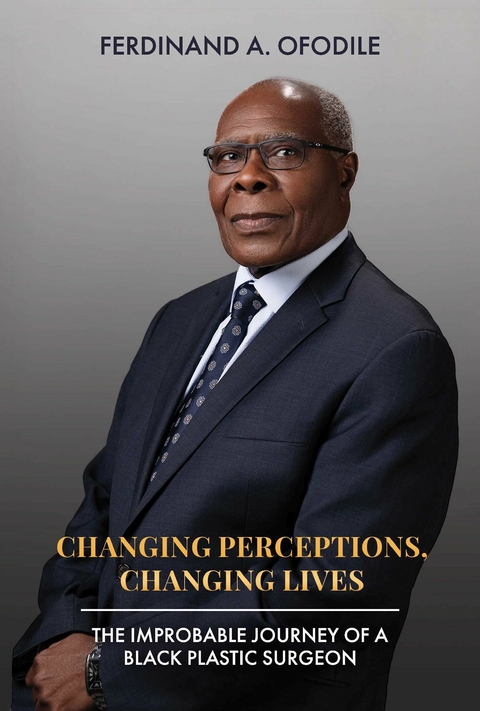

Changing Perceptions, Changing Lives (eBook)

344 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-5313-8 (ISBN)

Professor Ferdinand Azikiwe Ofodile is a US trained, and Board certified plastic surgeon. He retired as Clinical Professor Emeritus of Plastic Surgery and Special Lecturer at Columbia University, New York, after holding the positions of Program Director of the Harlem Hospital Plastic Surgery Program, Harlem Hospital Site Director of the New York Presbyterian Hospital (Columbia/Cornell) Plastic Surgery Program. Upon completing his high school education at the Prestigious Government College Umuahia in Nigeria, Professor Ofodile was admitted to Northwestern university in Evanston/Chicago, Illinois where he obtained his BSc and MD degrees. He went on to complete his training in General Surgery and Plastic Surgery, capped by a Chief Residency/Fellowship at Mayo Clinic in Rochester Minnesota. Professor Ofodile has published many scientific articles and contributed several book chapters. He has received many honors. Professor Ofodile is married and has four children.

Changing Perceptions, Changing Lives is a compelling account of the struggle to redefine Black beauty through research, thereby, changing the notion- the old maxim that to be considered beautiful one has to look Caucasian. In the book, professor Ferdinand Ofodile captivates us with his narration of his journey from Nnobi, a small village in rural Nigeria to America where he attained the distinction of becoming the first Black plastic surgeon to be appointed a Clinical Professor Emeritus in the specialty of plastic surgery. After finishing high school education at Government College Umuahia, the prestigious, British-style boarding school in Nigeria, professor Ofodile was admitted to Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA with a scholarship from the coveted African Scholarship Program of American Universities ( ASPAU). Upon his medical education, also, at Northwestern University, Dr. Ofodile pursued his surgical and plastic surgery training in New York, capped by a chief Residency/Fellowship at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Dr Ofodile then returned to Nigeria to teach at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria's premier university. In 1982, he returned to the USA as Chairman of the Harlem Hospital Plastic Surgery Program, and Assistant Professor of Surgery at Columbia University, New York. There were less than fifty practicing Black plastic surgeons in the USA at the time, a pitiful number compared to White plastic surgeons in the country. To make matters worse, there was general misconception of Black aesthetic features, Black plastic surgery and Black plastic surgeons as a group. Professor Ofodile became part of a small vanguard of Black plastic surgeons that, independently, committed their research and careers to changing those misconceptions. In his book, professor Ofodile gives a fascinating step by step account of his contributions to that effort. In spite of his accomplishments in his adopted country, Dr. Ofodile did not forget his country of birth, Nigeria. He continued to promote progress in Nigerian Universities through faculty development and visiting professorships. His medical missions in Africa and the Caribbean changed and saved lives. In October 2022, he received a National Honor Award from the President of Nigeria, General Muhammadu Buhari.

CHAPTER 2

FAMILY LINEAGE:

HERBALISM AND MYSTICISM

The West Africa magazine published an article in the November 3, 1980, issue, provocatively titled “Which Doctor for Africa.” In it, the author posed a controversial question: “Should traditional medicine be recognized and practiced officially in Nigeria to complement the shortage of medical personnel?” Demands by politicians and other stakeholders for the official absorption of traditional healers by the government into the national healthcare system had raised alarm among practitioners of Western medicine. Contentious and, sometimes, ad hominem debates in the media between the leaders of both camps erupted.

As a senior lecturer and consultant in Plastic Surgery at the University of Ibadan, I wrote an article in the Daily Times newspaper criticizing the efforts to bestow equal status to traditional medicine. That elicited a furious and vitriolic rebuttal in the same newspaper from the chairman of the Traditional Medicine Board, Chief J. O. Lambo. Declaring our two write-ups outstanding contributions to the debate, West Africa magazine in the 1980 article profiled them in tandem, leaving the readers to decide for themselves. As I look back at the debate, being a descendant of a line of famous traditional medicine practitioners during their time, I find my position of asserting the superiority of Western medicine quite knuckleheaded.

My Paternal grandfather and great-grandfather were renowned herbalists and spiritual healers. They were members of the Igbo tribe, one of the three largest of the approximately fifty-two tribes in Nigeria. My ancestors lived and practiced in Nnobi, our village, located in the present Idemili local government area of Anambra state of Nigeria and inhabited, then, mostly by farmers. Stories of their exploits still reverberate within our ancestral clan, and fascinated and frightened us as children and young adults. I was rumored to have inherited my grandfather’s healing powers and spiritual prowess as his reincarnation in my generation. However, since I became a plastic surgeon and not an herbalist or spiritualist, legend has it that those powers inherited from my grandfather morphed into aptitude in “Western medicine” and fueled my achievements in plastic surgery.

My mother, Nora Eruchalu, on the other hand, came from a family line that valued education and were early converts to Christianity. It is claimed that I inherited my proficiency in academics from her side of the family.

Because I was born and grew up in the newly developing city of Onitsha, while my extended family resided in our village, my recollections of my ancestors depended less on my personal interactions with them and more on the stories that I heard from the few people of that generation that were alive when I reached the age of awareness. My paternal and maternal great-grandparents and my paternal grandfather had died before I was born.

My paternal great-grandfather, Isigwe, had four children: my grandfather, Ikefunanya Ofodile; his two brothers; Udoagbala and Udo, and his sister, Ukagbala. Ikefunanya, who was the oldest, married three wives and was blessed with eleven children—six daughters and five sons. Wife number one, Nnwoye, was my grandmother. She had five children; four girls named Nwa mgbeke, Mary, Nwanne bu uzo, and Philomena in that order. My father, Julius Okoye Ofodile, was her fourth child and only son as well as the first son of my grandfather. The second wife, Udennwa, also had five children; four boys named Joseph, Alphonse, Michael, John, and one girl called Josephine. The third wife, Nne Anukwanke, had one daughter called Anukwanke. Ikefunanya’s first brother, Udoagbala, had five daughters while the second brother, Udo, had one son and three daughters. Udo, the youngest brother of my grandfather, lived in a hut in our ancestral compound in Nnobi with his children. I had the good fortune of experiencing his company. He was a great storyteller. The children gravitated towards him and he regaled us with accounts of the exploits and medical and magical prowess of my grandfather and great-grandfather. Every night he played local folk songs on his Ubo—a locally made musical instrument known in English as the thumb piano, in his sitting room lit by locally made Npanaka lanterns.

According to Udo’s account, my great-grandfather Isigwe was a highly regarded traditional healer. His son, Ikefunanya, my grandfather, inherited those powers from him. Ikefunanya’s reputation and fame, eventually, surpassed those of his father. His prodigious knowledge of local flora and their application to the treatment of different diseases was legendary. Patients consulted him from far and wide for treatment of a wide range of diseases and for spiritual protection. He was among the few in that era who dared to travel by foot to distant towns and villages to minister to clients. Udo would keep us transfixed with stories of how our grandfather battled evil spirits and nefarious characters along the trails in the dense forests during his journeys. Evil men such as kidnappers for human sacrifice and slave traders were in abundance at the time and constituted ever-present threats.

My grandfather was rumored to possess mystical powers that helped him avoid capture. He would metamorphose into a lion or a dangerous snake when he perceived approaching danger and revert to his human form after the danger passed. The most fantastic tale was that if he heard suspicious footsteps in the middle of a forest, especially at night, he would lean against a big tree in the forest and become invisible except for a pair of eyes perched high on the trunk of the tree. That sight frightened away even the most hardened of men. As children, we were simultaneously mesmerized and awed by such powers. We were too young to question the authenticity of the accounts.

When my grandfather died, his spirit was believed to have reincarnated as Joseph, the first son of his second wife, skipping my father. My grandfather’s spirit was then reincarnated in me in the following generation.

Joseph picked up from where Ikefunanya, his father (my grandfather) left off. He did not attend formal school, but developed his own reputation as an herbalist and a spiritual healer. Joseph liked me immensely and I spent a lot of time with him during my holidays at Nnobi. I was most captivated by two areas of his metaphysical practice. The first was based on the local people’s belief that deaths, major diseases and misfortune were caused by evil spirits and nefarious acts of enemies and rivals. Western scientific analyses and medical treatments were scorned. Patients with mental and physical illnesses, business and love problems came calling for him to drive away or protect them from the causative evil spirits and mystic forces. He had medicines for every medical, social, and spiritual issue. There were potions and amulets and udu (clay pots filled with spiritual artifacts) for protection of property and businesses, for success in love and any other conceivable undertaking.

Most of the consultations were done in the sacred healing hut or shrine (Okwu Mmo), known as Ababa which he had inherited from Ikefunanya, his father. The shrine was a dark hut filled with a variety of concoctions, clay pots and gourds covered with animal blood and feathers, as well as wooden statues representing different ancestral spirits. The inside of the hut was truly intimidating and patients must have surely felt the presence of our ancestral spirits inside it.

Every consultation started with a ritual. Each native doctor had his own ritual, as did my uncle. His was engaging, and I paid attention. The consultations started with informal conversation with the new patients and quickly proceeded to the formal part, where Joseph would flip a dried bird skull up a cord that was threaded through it and fastened to the roof. As the bird skull, known as Nwaifulu, slowly descended down the cord, a voice emanated from it, calling Joseph’s name and reciting all his titles. It would then announce the name and particulars of the patient, followed by the problems that brought him or her for consultation. Joseph would engage the skull in a conversation throughout its descent, during which he would elicit from the Nwaifulu the details of the patient’s ailments; which human beings or spirits were responsible for them, and how imminently and aggressively the threats needed to be addressed. By the time the skull reached the end of the rope, the patient and the visitors, including me, were dumbfounded and impressed, wondering how a skull could talk, let alone know so much about the patient. Joseph would then face the patient and continue with the rest of the consultation including the treatment plan, which would invariably involve invocation of ancestral spirits and animal sacrifice.

A case in point occurred when I was on holiday, during my first year at Government College Umuahia (GCU). A middle-aged woman had come from the city of Aba in the Eastern Region of Nigeria to consult with Joseph. The woman had been married for many years as the third wife of a polygamous man, whose first two wives had not provided him a male child—an unacceptable circumstance for an Igbo man. She looked stressed and depressed. As soon as the patient walked into the shrine, before the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-5313-8 / 9798350953138 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 12,9 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich