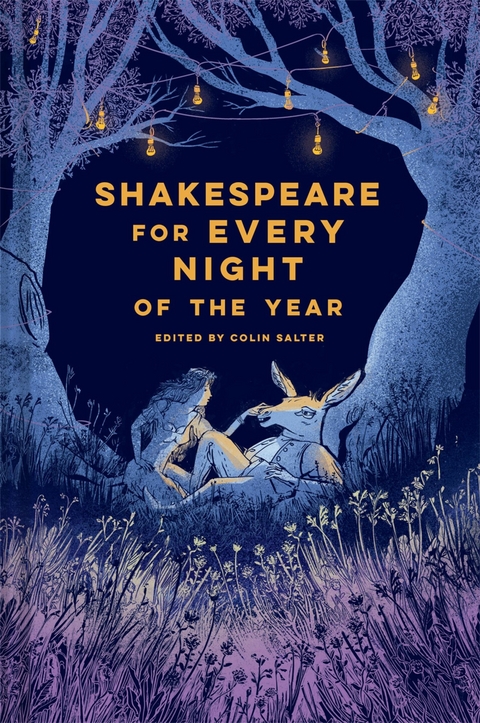

Shakespeare for Every Night of the Year (eBook)

528 Seiten

Batsford (Verlag)

978-1-84994-951-4 (ISBN)

Chosen especially by a Shakespeare fanatic to reflect the changing seasons and daily events, the entries in this glorious book include:

Romeo and Juliet on Valentine's Day.

A Midsummer Night's Dream in Midsummer.

The witches of Macbeth around their cauldron on Halloween.

Also featured is one of Shakespeare's only two mentions of football for the anniversary of the first FA cup final.

Beautifully illustrated with favourite scenes from Shakespeare's best-loved plays, this magnificent volume is a fun introduction to the well-known work and lesser known plays and poetry and is designed to be accessible to both adults and curious children.

Keep this book by your bedside and luxuriate in the rich language of the greatest writer the world has ever known, for entertainment, relaxation and timeless wisdom every night of the year.

Colin Salter is a former theatrical production manager, now a prolific author of literary history. In the course of fifteen years he worked on well over a hundred plays including, of course, many by William Shakespeare. For Batsford he has written 100 Books that Changed the World and 100 Speeches that Changed the World. He is the author of a biography of Mark Twain and is currently working on a history of the books in one family's three-hundred-year-old library. He delights in the richness of language, whether William Shakespeare's or PG Woodhouse's. He lives in Edinburgh with his wife, dog and bicycle.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 12 black and white illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Lyrik / Dramatik ► Dramatik / Theater |

| Literatur ► Lyrik / Dramatik ► Lyrik / Gedichte | |

| Schlagworte | academia • After Dinner Speech • All's well that ends well • A Midsummer Night's Dream • Anthology • Antony and Cleopatra • As You Like It • a winter's tale • Bard • Christmas • comedy of errors • complete works • Coriolanus • Cymbeline • elizabethan • extracts • First Folio • Gift • Halloween • Hamlet • Henry IV • Henry V • henry vi • Henry VIII • Julius Caesar • King John • King Lear • Love's Labour's Lost • Macbeth • Measure for Measure • Merchant of Venice • Merry Wives of Windsor • Midsummer • Much Ado About Nothing • Othello • Pericles • PLAYS • Readings • Richard II • Richard III • Romeo and Juliet • Shakespeare • shakespearean • sixteenth century • Sonnet • Stratford-upon-Avon • taming of the shrew • Theatre • The Globe • The Tempest • Timon of Athens • Titus Andronicus • Troilus and Cressida • Tudor • Twelfth Night • Two Gentlemen of Verona • Valentine's Day • weddings |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84994-951-4 / 1849949514 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84994-951-4 / 9781849949514 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich