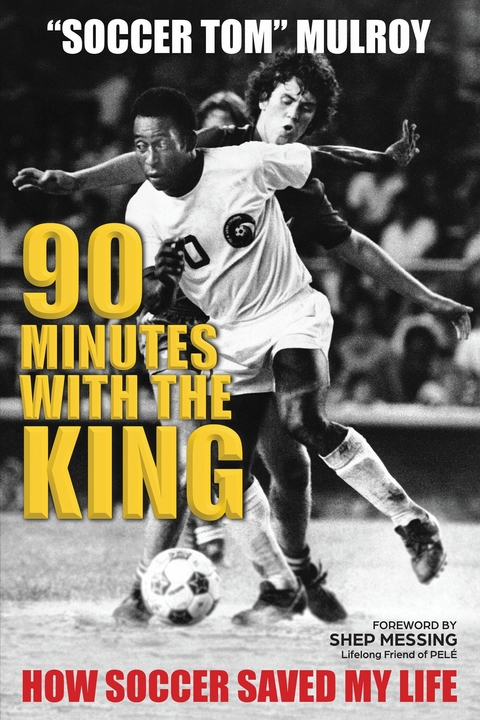

90 Minutes with the King (eBook)

326 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-1109-1 (ISBN)

Experience the remarkable journey of a boy from New York who began life behind the eight ball. Growing up on the edge of poverty, he battled dyslexia and endured the pain dealt by an alcoholic father. From his single mother, he learned grit, empathy, and selflessness. At age 12, still torn between right and wrong, he is introduced to soccer. The Beautiful Game saves his life. Outside his neighborhood, soccer is seen as an ethnic cult, a sport played by the weak and people who don't speak English. Nothing dents the boy's will. He follows his idol, Pel like a North Star and dreams of becoming a pro. His dream becomes an obsession, his exit ramp off a road that would have left him "e;dead or in jail."e; In his early teens, he plays for coaches who shape him as a player and a man. He struggles in school, but he has found his purpose. He plays or practices fifty hours a week. Some days he hitchhikes to games, other days he spends entire afternoons lashing balls off the brick wall of Cinema 45. No one will outwork him; nothing will distract him. Seven years after he first touches a ball, Tom Mulroy becomes a professional soccer player. Against billion-to-one odds, Soccer Tom experiences the dream of every soccer player and fan around the world.

CHAPTER SIX

Captain’s Armband

I played in my first official soccer game on September 28th, 1968, my 12th birthday. It was an introduction to a new sport, and to new and distinct cultures. I had opened a door to a world that was way bigger than the one I lived in. Everybody had a heavy accent, whether German, Yugoslavian, Hungarian, or Norwegian. Whenever I carpooled to an away game, the ethnicity of the driver would determine the language I would hear that day and what kind of music played on the built-in cassette tape or the eight-track player. We played in every ethnic neighborhood in New York City, say, in Astoria, to play the Greek Americans, or in Brooklyn to face the Italians. You name it, if there was an ethnic neighborhood, they had a soccer team playing in the German American League. I was learning to open my mind and think beyond my little world. This was an atmosphere where a young man could hone his people skills and prepare to be successful in all walks of life.

We trained twice a week, and at that time the youth teams played on Saturday and the men’s teams played on Sunday. Our coach, Mr. Sautner, would invite me to watch him play with the over-30 team. They would play a match and the first team would play right after, which was like a double-header for me every Sunday. Soccer was becoming a huge part of my life. Off the field, I was still spending time with John and his friends. But for once I was on the path toward a healthy addiction, the same addiction that people have for soccer around the globe.

About halfway through the season, I got a new perspective on what soccer means to the people in my new community. Our captain, Danny Janes, had lost his mother. It was the first funeral I ever attended and an experience I’ll never forget. The team was asked to come to the funeral in our uniforms. We lined up on both sides of the coffin as the priest gave the eulogy. It was emotional and moving. Now, people not steeped in soccer might wonder why someone would ask kids to wear their soccer uniforms at a family funeral. But that’s what our club had become. We were more than friends and teammates; we were extended family. I didn’t realize it then but I know it now: standing in our uniforms by Danny’s mother’s coffin was our way of showing our love and loyalty for our teammate and his family.

Back then, no matter your age, you played 11 versus 11. You played on the same size field as the adults. You played with the same size goal, and, in most cases, with the same size-5 ball. Think about the effort asked of an eight-year-old to get from one goal to another 120 yards away. It was also a challenge for young goalkeepers, who couldn’t come close to reaching the crossbar eight feet off the ground. Back then, the standard soccer formation was the WM system, comprised of one goalkeeper, two backs, three midfielders, and five forwards. This is how the numbers on the uniforms went: Goalkeeper #1, Right Back #2, Left Back #3, Right Midfielder #4, Center Midfielder #5, Left Midfielder #6, Right Winger #7, Inside Right #8, Center Forward #9, Inside Left #10, and Left Winger #11.

After each game, our shorts and socks were ours to take home. Our coach, Mr. Sautner, would collect our jerseys to take home to wash. At the next game when Coach handed you a shirt, you knew by the number if you were starting or not, and you knew your position and your responsibility for that game.

That year I played in my first indoor tournament, the Rudy Lamonica Oceanside Tournament. At the time, it was the first and only youth indoor soccer tournament held in the country. I remember seeing Rudy’s picture in the high school trophy case as we entered the gym. He was a legendary youth player before bone cancer took his life at age 17. His parents would go to the tournament and help hand out trophies every year. I won my first trophy there. Launched more than 50 years ago, the tournament still takes place every year.

Later that season, I got picked to play on the German American League Boys’ All-Star Team. I played my first international game with that team at the Metropolitan Oval against a team visiting from Germany. I carry one vivid memory from that game. I was defending in front of our goal when I dove to head out a cross. Just after I put my head on the ball, a German forward swung his boot into my face. He was a split second late on his attempted volley, but he landed a direct hit on my front teeth. I was in serious pain, but this was 1969, before any concussion protocol. In fact, the medic or ref would simply ask you if you knew your name. Whether you did or not, as long as you could answer the question, you kept playing.

German American League Boys All-Stars 1969

Young Tommy Mulroy front row far right kneeling

Toward the end of the season, I got a thrill that I remember to this day. At the end of practice, Coach Sautner began to give one of his talks. Coach had a harsh German accent, and he stuttered a bit when he spoke English. He talked about working hard, improving over the season, and being a leader. He pulled out a captain’s band and described what that role meant. Then he looked at me and said, “Tommy, come here.”

As I walked toward Coach, a feeling of euphoria swept over me. Coach said I had earned this band through my effort and leadership. It was a moment that changed my life, a moment that gave me a huge shot of self-confidence. As a 12-year-old kid still trying to choose between right and wrong, this was a game-changer, even a life-changer.

It’s a moment that I share with others whenever I can. I share it when I’m giving coaching seminars for coaches. I want them to realize that they are not just coaching a “soccer kid,” but a little human. Those kids could use a pat on the back and a little positive support from someone they looked up to. When I am on the field working with kids, I aim to make every kid feel special. Sometimes it might be a little smile of approval, a smile that can turn something that seems trivial into something important, even memorable.

When I got home after practice that afternoon, I was still high as a kite. That night I couldn’t fall asleep. That was not unusual; I often had trouble drifting off after we won a big game. But this night was different. I felt like I was glowing. Looking back, this was truly my first soccer “high” across physical, mental, and emotional realms. You hear big-time athletes, musicians, and other successful people say how they can’t describe the feeling. I’m pretty sure that’s what I was feeling.

Later in life I would realize that this was a tipping point, a time when I stood at an intersection, one road full of death traps, the other leading to a life in soccer. Being on a soccer field felt so good, so motivating. I began training every free minute I had. It didn’t matter if the kids in the neighborhood wanted to play. I would happily dribble my ball up to Cinema 45 and pound it off the wall for hours on end. If I was working on my instep, I’d kick it off the wall 500 times with my right and then 1,000 times with my left, exactly how coach told me to do it. Somehow, kicking my ball always made me feel good. If I was having a bad day—maybe I had failed a spelling test—I could get my ball and juggle, kick it off a wall, or go for a run with it. The stress melted away. Soccer was beginning to become my personal identity.

One day early in the season, my aunt could not drive me to practice and I couldn’t drum up a ride, so I took my gym bag and started walking. We trained at Clarkstown Junior High, almost four miles from my house. About halfway there, I realized I was going to be late and maybe even miss the whole practice. So, I stuck out my thumb. I figured it was safe, because my brother and his friends did it all the time. It wasn’t long before I got my first ride as a hitchhiker. For the next few years, hitchhiking became one of my primary forms of transportation to and from soccer fields all over Rockland County and beyond.

The more I played, the more I wanted that high like no other. I would train and play between 40 and 60 hours a week. When my mom wanted me to become an altar boy with my brother at Saint Joseph’s, you can imagine how I reacted. I would have to miss all my games, since they took place on Saturdays. It was a battle early in the school year when the church was recruiting 13-year-old boys for the role. But my mom knew what soccer meant to me. She eventually relented, and I never missed a game.

I set my goals high. I wanted to be the best player in the world, the first American Pelé. At times I felt like I should have been born in Argentina, Germany, or some other country where soccer ruled. I was in the wrong place, I thought, but that didn’t stop me from training every day. I was not competing to be the best player on my team, my state, or my country. In my mind I was competing against some kid in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, or in the streets of Berlin, some kid who might be practicing harder and improving faster than I was. I wanted to be the best player I could be. According to the role models in my life, that meant no smoking, no drinking, and no wild and crazy behavior. It meant dead-on focus and hard effort. It meant teamwork. It meant leadership, and it meant choosing a path at this crossroads that would take me in the right direction.

My First...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-1109-1 / 9798350911091 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 11,9 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich