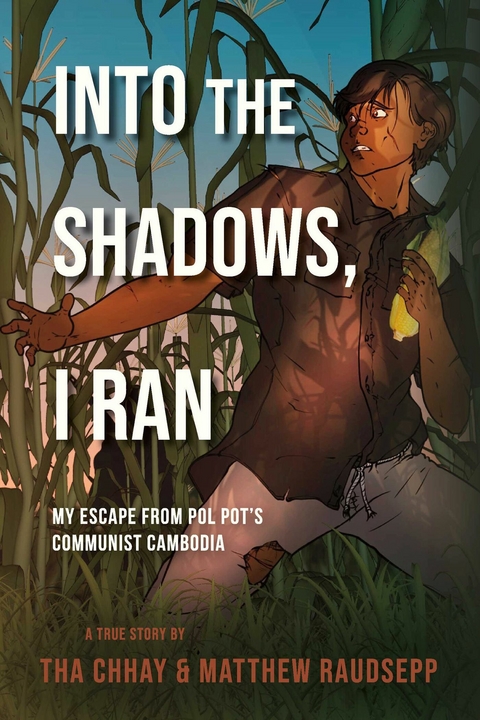

Into the Shadows, I Ran (eBook)

212 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-3458-8 (ISBN)

"e;Into the Shadows, I Ran"e; begins with the Khmer Rouge's forced evacuation of Cambodia's cities immediately after the fall of Phnom Pen and Saigon in April of 1975. The story traces Tha Chhay's attempted escapes from the forced labor camps when he was a boy. After the Khmer Rouge fell from power, he traveled extensively around Cambodia as a boy merchant. After buying and selling goods in different markets across Cambodia, he saved enough gold to hire a guide to take him across the land-mine fields into a refugee camp in Thailand. He persevered in the refugee camp for six long years. In the camp's small library, he saw a picture of Neil Armstrong and Edwin "e;Buzz"e; Aldrin place the American flag on the moon. He knew that Cambodia wouldn't get their flag up there in a million years, and decided America was the best country to take him away from the political turmoil of his homeland. In the camp of 28,000 refugees, he was chosen to be sponsored to live in America. He was eventually sent to be settled in Seattle, Washington, where he still lives today. His quest to survive and make a living forced Tha Chhay to harness his inner talents and skills. This book is a window into a rich culture steeped in the history of the Far East, at a time of great upheaval and personal tragedies. Tha Chhay's testament to the horrors of the Cambodian genocide offers perspective into current political turmoil around the world. He hopes countries never experience this type of genocide again.

PROLOGUE

“When the Elephants Fight, it is the Grass that Suffers!”

African Proverb

Distant Booms and a New Hope

Cambodia, January 11, 1979 (Southeast Asia)

The Khmer Rouge holocaust ended quickly, just as it began. Early on January 11th, we began to hear what sounded like explosions in the distance. Distant booms sent birds in the nearby jungle flying in swarms into the early morning sky high above the tall coconut trees on the rice field’s edge where we worked. That morning, hundreds of us, with our straw hats shielding us from the intense sunlight, walked among the tall rice grass, cutting and carrying the grass for harvest. Throughout the morning, the rumblings became louder. At times, I stopped my work to look toward the jungle and across the wide expanse of fields to discover the source of the sound. What horrors were the Khmer Rouge committing this time? We had no idea what was happening, and none of us in the village could have anticipated the events that would take place later that day.

Just before the arid afternoon sun reached its zenith, two objects out of nowhere whistled overhead until landing in giant explosions on the edge of the field, one on a large Khmer home that overlooked the field and the other in the dry field, spraying the red earth in all directions. The ground shook, as small sediment from the explosion landed around me. Yet it was not enough to move me from the field, where I continued to work on in shock. The imaginary shackles kept my bare feet immovable from the dry, cracked ground. Others around me did the same, immovable from their work, daring only enough to look up at one another with wonder in their eyes. Should we run for cover and risk harsh discipline from our longtime captors, or do we stay and wait—wait for the final breath that so many of our relatives and friends had taken in the past three years, eight months, and twenty days.

The Khmer Rouge soldiers ran out to the field, shouting for us to go into the jungle with them. They yelled, “We are one village. We must stay together and fight.” Some of the workers, not knowing what to do and still in great fear of our longtime captors, followed them off into the jungle. The rest of us ran toward the village. We ran there because that is where others ran. We did not know who was bombing the field and the village. My aunt, uncle, cousins, and I lay flat on the ground near our huts.

From the nearby highway, tanks unloaded a volley of artillery fire into the field and the large Khmer homes in the village in an attempt to drive away the Khmer Rouge soldiers. After several hours passed, the shooting stopped. The Khmer Rouge were gone. The eighty or so of us who remained, slowly got up. Some grabbed white hand towels or anything else that could be found of white material to waive at the troops. We ran toward them, not knowing who they were, or if they were going to shoot us too, but anyone who scared away the Khmer Rouge was more likely to be friend than foe. The soldiers were horrified by our emaciated appearance. Most people in the village were in their twenties and thirties, yet many looked like old men and women. The Vietnamese and Heng Samrin Cambodian soldiers welcomed us and offered us food. After we were given food, we were told to return to where we came from.

It did not seem real, as if it were a trick or a very vivid dream. I could not believe this to be true. Suddenly the realization occurred to me that, “Yes. I was free.” It took an hour for this idea to fully sink into my mind. The Khmer Rouge were no longer in power, and we were free to leave. We were no longer condemned to live in the controlled village life that we had come to accept. The blackness that had hampered our spirits was suddenly brushed aside. Our black clothes no longer mirrored our despair. We no longer even had to wear the tattered black clothes, but that was all there was to wear. On Highway 5, Aunt Oiy’s family and I retraced the steps that we had taken almost four long years before, back to our homes in Sisophon, in northwestern Cambodia. I was thirteen years old at the time.

Along the road ahead of us, our last remnants of disbelief vanished as we came across the bleeding bodies of recently killed Khmer Rouge soldiers. I think I recognized one of the bleeding men, a soldier who ordered a friend of mine to follow him into the jungle. My friend never returned, but I did see this soldier again often enough, ordering us around or reprimanding someone for some petty, slight infraction. We had to walk on the old, dilapidated highway with caution, as we could still be recaptured by soldiers hiding in the vicinity of the highway. A great heaviness fell off my shoulders, and I actually felt lighter. The years of waiting, surviving, and hoping had come to an end. Our toils had meaning, other than that of day-to-day survival for food. My family did not suffer the hardships in vain. There was now hope, like never before, that I would be reunited with my whole family once again. I kept looking over my shoulder, expecting someone to spring up onto the roadside from a hidden place behind bushes or scattered trees.

My aunt, uncle, cousins, and I headed back toward Sisophon. It took us nearly two days of walking, as we were exhausted and had not had much food for months. I parted from them on the outskirts of the city, as we took different roads to return home. Continuing down the highway alone, I began to feel unfamiliar with the surroundings. The many changes I perceived around me did not seem possible. I was filled with a sense of urgency to quickly reach my old home, to once again be part of the vague and distant dream in my heart. At first, I disregarded the differences all around me, but I soon realized that the small temples and attractive, large homes on the edge of town were no longer there. Yet the hills were in their familiar place. I could not have lost my way as I traveled along this road so many times in my childhood. When I finally reached my father’s land, I knew that I was in the right place. I recognized my family’s mango and coconut trees. But to my astonishment, my boyhood home was completely torn down. Nothing remained, except for a piece of the kitchen floorboard which laid on the ground near the base of a large tamarind tree. Even the small, sacred spirit house, on the corner of where our house once stood, where my mother’s ashes had been kept, was completely smashed. Bits and pieces of wood lay scattered about the area where it once stood, including a tip of the small Garuda-winged roofline.

As I observed the scene, the shock of the unreal filled my mind, and the pit of my stomach churned in despair. Terror and the deepest depths of loneliness and pain crowded out my thoughts until rationality slowly returned. I was hungry, fearful of what had become of my father, brother, and sisters. A feeling so deep from within cried out. I could not name it. I fell to the ground, sitting on the place where my pet chicks and ducks had once played, years ago, beneath the place where my boyhood home once stood . I felt a sense of safety being on my father’s land, yet suddenly the tears came and flooded my face with such extreme anguish and pain that I astonished myself, having been numb for so long to the tragedy that encompassed me back in the village. Where was my family?

After dispelling some of my pain and regaining my level-headedness, I decided that I had better find some food, and I started to look around to see if I could recognize anyone. I did not see any familiar faces. In wandering around the area, I found an abandoned warehouse where stacks of rice were kept. As I was one of the first few back, I found some giant bags of rice left behind by the fleeing Khmer Rouge soldiers. Being too small and skinny to lift the bags, I punctured them and filled up some thin metal buckets that I had found. I balanced the pails on a pole as I carried the rice back to my family’s land. I went back and forth like this for some time, guessing that food in the weeks ahead would be scarce and very expensive.

With my heart centered on hope—hope that I would see my whole family again someday, as I had hoped each day in the village—I built a small make-shift hut on my family’s land. I could barely stand the idea of my father, stepmother, sisters, and brother not returning. Days passed, turning into a week and then two weeks. I had my food now, consisting of the rice and fish from the nearby river, but no family. I was thankful to at least know that my aunt’s family had survived. Where were my father, stepmother, and brother and sisters? Where did they go? Were they safe? I could not believe that I was to be left alone. At night, I frequently had nightmares, memories of horrific scenes I had witnessed. In my dreams, I played with childhood friends whose whereabouts I no longer knew, or I sat in a circle with my family having a meal, sharing laughter over friendly conversations. I reminisced about the earlier days of my pet cow and dog on the farm. I would wake up sweating, in complete darkness, lonely and fearful. The nighttime frog sounds would sometimes stop completely, and there would be complete silence, except for the sudden and intermittent bird call in the early morning, from an Asian koel (cuckoo), that would bring me back to reality.

During my wait there, I tidied up the area of my family home and fished in the nearby river to keep myself busy. One day nearly a week later, I recognized a former neighbor who had lived a street down from where our family’s home once stood. And then, after two weeks of waiting, someone came to my makeshift home. When I recognized him, I...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.12.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-3458-8 / 9798350934588 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,0 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich