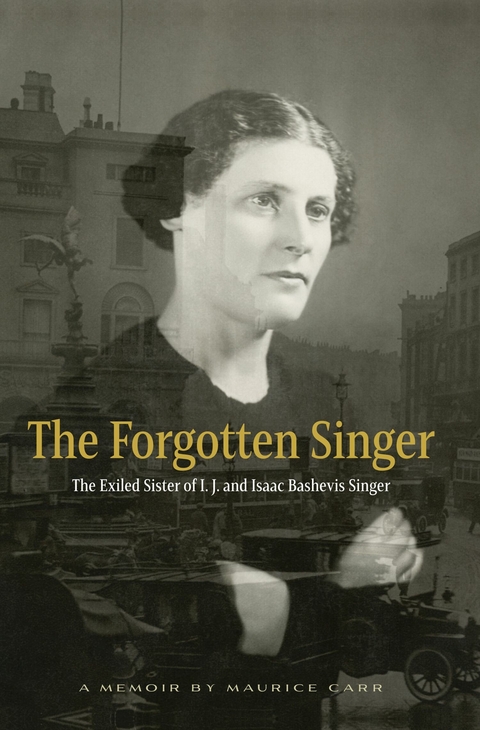

FOREWORD

“The day of days dawns. I go to Calais. On the dockside I catch sight of Lola wrapped in a sealskin and Hazel in a bright red coat, The Old Nursery Rhymes upheld on both palms, descending the gangway of the ferryboat. I rush to meet them, sprain my ankle, and keep running for hugs and kisses.”

These are practically the last lines of my father’s memoir.

The little girl in the red coat is me, and I still like red.

So here I am sitting in front of a typewiter (only it’s a computer), just as I saw my father doing from as far back as I can remember, writing and rewriting the first sentence of his article, throwing the paper away and starting again, the papers flying to their last resting place, the wastepaper basket.

Till the evening before the deadline when he used to take me out in our battered old green car and we drove to the post office, which stayed open all night, to send his article off to the newspaper.

When he retired he didn’t have a deadline anymore, but he went on writing, so … the paper flew.

One of my first memories of my father is sitting with him, my mother, Lola, and my grandparents Esther and Avrum in my grandparents’ house in London. A house I remember as dark, damp, cold, and dreary.

Esther, whom everyone in the family called Hinde, was a dumpy figure always dressed in dark clothes, black hair flaring out on either side of a white part in the middle and blue eyes so pale they were almost transparent. She was a somewhat frightening figure.

To me of course she wasn’t the writer Esther Kreitman, sister to Israel, Joshua, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. I knew nothing about her unhappy childhood; I knew nothing about her being the first of the Singer siblings to write.

I was a little girl, and to me she was just Buba. My grandfather Zeida was more jovial.

We used to huddle in front of a fire in the chimney that never seemed to warm anything. If there were sunny days, and there must have been, I don’t remember them.

I also don’t remember her paying any particular attention to me. Not the rosy-cheeked kind of Jewish grandmother who bakes you apfel strudel.

Come to think of it, she must have regarded me as a disaster, because I was the reason her son married my mother.

Because (and this I know from overheard conversations between my parents) Esther had always thought her son would live with her for the rest of her life, that they would sit together at the kitchen table writing.

So my mother’s eruption into their cozy life was a tragedy she never accepted.

This tragedy happened because of the Second World War.

One day A. M. Fuchs, refugee from Vienna and the Anschluss, put on his hat and his gloves and took his daughter Lola along to pay his respects to that other well-known Yiddish writer, Esther Kreitman.

Royalty paying a visit to royalty.

Esther became my grandmother.

My father was bowled over by Lola’s beauty and also the chutzpah with which she talked back to her father, he who was always very deferential to his own mother. At the time Lola had a husband who had stayed in Vienna, so Esther thought it safe to suggest her son show her around London. There would be no danger in his having a relationship with a married woman.

There she made a fatal mistake.

Because I arrived on the scene. Lola got a divorce, and my father used to describe the scene where, standing in the kitchen where everything important happened, he put his arm around my mother’s shoulder, and in those days that meant “We’re getting married.”

So I was born during the war, not a cheerful time.

Around the chimney fire I remember my mother in the blonde halo of her hair and Esther in the dark frizz of her curls saying nasty things to one another while my father perched uncomfortably on a stool between them, a long, thin, timid, uncertain young man not knowing how to deal with these two female furies, the one feeling she’d rescued him from an overbearing mother, the other that her son had been stolen away from her.

Maurice loved his mother and felt his mission in life was to look after her and protect her, so falling in love with Lola was a bit of a tragedy for him too.

I think he felt guilty about this all his life.

My father during the war had been working for The Daily Telegraph and then Reuters and the BBC. One of these asked him to change his name, as Kreitman, they said, was unpronounceable. So he became Maurice Carr. After the war he was sent as a foreign correspondent to Paris.

My father’s ambition was to become a writer. Before I was born he had published several books. But because he married and had a child he felt he had to concentrate on being a journalist in order to earn a living.

Of this I have always felt guilty.

Sometime before he died he seemed to relive the scene in Antwerp when he and his mother were on their way to Poland and she fell down in front of a tram foaming at the mouth in an epileptic fit.

And he would weep uncontrollably. My mother and I wouldn’t know what to say to comfort him.

Maybe Maurice is now sitting together with Esther at a heavenly kitchen table writing.

To write—that was his main aim in life.

Maurice wrote slowly; it didn’t come easily to him, contrary to his uncle Bashevis, from whom the writing seemed to flow.

Maurice had mixed feelings about Bashevis.

I myself only met him three times, but I could see he was a man full of contradictions.

THE FIRST MEETING

The first time I remember meeting my great-uncle Bashevis was at Orly airport in Paris. He wasn’t yet the well-known writer, winner of the Nobel Prize, but a Yiddish writer known only to the happy few. He was on his way back from Tel Aviv, where my parents lived and his plane was in transit for New York. He had told my father he would like to meet me.

So I go to Orly and see from afar a man arguing with some sort of official in uniform. I recognize immediately this thin man whose clothes seem to float around his body and the back of whose head has the same massive bulbous shape as that of my father. I go to talk to the customs official and get permission for him to come out of the embarkation zone.

We go to a café, sit down, he turns an icy blue look on me, and says, “I’m not at all interested in family, OK?” It was only years later that I wondered why, if that was the case, he had wanted to meet me.

Then he talks to me about a painting of mine he had seen in my parents’ flat and that my father had given him. He had put it in his suitcase. It showed a pious, bearded Jew brooding over an empty chessboard.

My uncle then flew off—

THE SECOND MEETING

The second time I met him was at the reception his Paris editor gave for him after his Nobel Prize. I’d been living in England when he got the prize, and when I heard on the BBC “The Nobel Prize for literature is …” I knew seconds before the announcer said it that it would be Isaac Bashevis Singer.

I didn’t quite know what I was doing at this reception or who had invited me. I wandered around the room, and every time I glanced toward Bashevis he seemed to be looking at me; his pale blue eyes were like lakes filling up the whole room. I finally went up to where he and Alma were standing and said to Alma, “I’m Hazel.”

“I know,” she said. “I recognized you. You look just like your grandmother.”

Oooh, I wasn’t happy to hear that; my grandmother was very short of being a beauty—

THE THIRD MEETING

The third time I met him I was on a visit to New York.

I went to ring at the door of their apartment. It opened. Bashevis stood there, and the first thing he said to me was, “I still have your painting.” He started to look for it and eventually found it under a pile of books and magazines.

Then Bashevis took me to lunch in one of the cafeterias he used to go to. Even if one cares nothing about family a niece has to be fed. While we were there people kept coming up and saying how they loved his books. To each one he said the same words: “You have made my day.” I took this as ironic, but they took it seriously.

Then I accompanied him through some dark streets. He stopped in front of a house and said goodbye. I was sure he was going to see one of his mistresses.

My father used to tell me that Bashevis had told him that if he wants to be a good writer he should have a mistress who lives on the sixth floor. Climbing all those stairs would be good for the creative adrenaline.

He also one day said to my father, “Your mother was a madwoman.” My father didn’t speak to him for years after that. Alma wrote a letter saying he didn’t always mean what he said and to please forgive him.

Bashevis told me on that street that my father had written to him saying he was going to commit suicide. Bashevis said to me, “I’d rather he’d written to me after committing suicide.”

That left me voiceless. Later I understood this to mean he would have liked a message from the other side.

I said to him, “Do you think we will meet again?”

He answered, “If God wills...