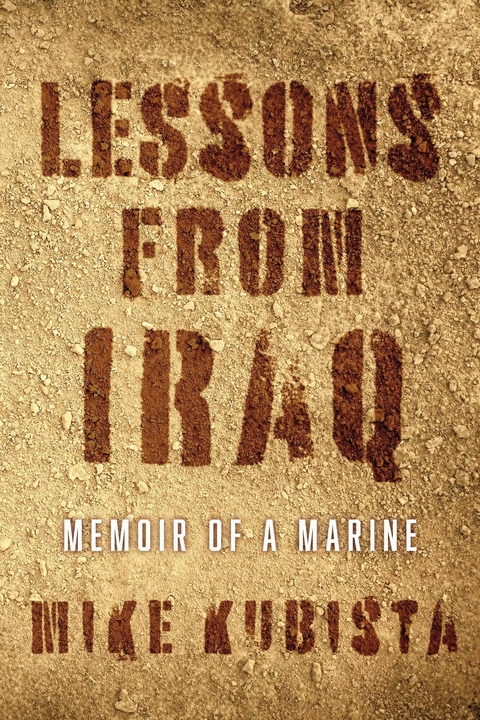

Lessons from Iraq (eBook)

284 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-8219-2 (ISBN)

Iraq was a strange war in that so few members of the American population were actually affected by it. Soldiers went to war while kids back home played video games of the same battles men were fighting. Many Americans knew people who served, but it was a relative few who went back again and again while society rapidly moved ahead back home like nothing was happening. War creates gaps between those who experience it and those who don't. Lessons from Iraq closes some of those gaps. Mike Kubista was a young Marine machine gunner sent in from the very beginning. His stories put you in place, let you walk along the chaos, and feel the world through his eyes. Part of this book is also about giving people context. There are a few common stories told about Iraq and what happened there, but never from people who were actually there. Mike weaves in the history, politics, and decisions made that ultimately led to the destruction of so many lives even as Iraq was on the verge of electing its first non-sectarian government. This is the story about how it all fell apart.

Rapid Fire

In the spring of 2003, out front of an abandoned bank a few miles south of Baghdad, Sergeant Stanley sat down to have breakfast in the passenger’s seat of his Humvee. Stanley was a short, thick-muscled black man who always wore a smile, treated everyone with dignity, and was quick to give his friendship. While Stanley was eating, an Iraqi man walked up to his Humvee, said “Good morning, mister,” drew a pistol, and shot him in the face.

Stanley should have died that day in front of the bank. The shot was point blank and he wasn’t wearing his Kevlar helmet. The bullet should have smashed straight through the spongy bone between his eyes. Instead, it ricocheted off his Oakley sunglasses and careened up his forehead, leaving only a graze wound and a muzzle burn the size of a quarter from the discharge of the round. After the shot, Stanley sprang out of his seat and shoved the Iraqi man, shouting, “Shoot him, shoot him, shoot him!”

In the short time it took the Marines in Stanley’s team to respond, the man cycled through his clip. The second shot hit Stanley in the chest, but his flak vest absorbed most of the blow. The third shot zipped through the open door of the Humvee, passing inches behind the neck of the driver and smashing through the window on the other side. The fourth shot bounced off the rifle hand guards of a Marine running from his post on the street to respond. The shots were good, and the Iraqi man was willing to die for what he believed, but he didn’t accomplish his purpose. Seconds after the man began firing, seven bullets passed through his body, fracturing and tearing as they went. The man fell to his knees and swayed. A corporal from Stanley’s team stalked up behind him, leveled his muzzle at the back of the man’s head and squeezed the trigger, painting the street with brains and bits of skull fragment.

Stanley re-gathered himself and went back to work.

***

Sometimes I close my eyes and see bodies of men strewn along the street, bodies shredded by bullets and ground to mush under the treads of armored personnel carriers. Sometimes I hear a wail in my mind that transcends everything I thought I knew.

I’ve been in Iraq about a month, and a bear of a man approaches me. I’m working crowd control, turning away Iraqi civilians who want to get home past our roadblock. Heavy attacks are raging a few miles ahead and we don’t want civilians there. We don’t want dead civilians. As the man gets closer, he makes me feel small, frail. He’s full-grown, thick-chested and heavy through the gut with a jet-black beard and fury in his eyes. I’m just a kid, nineteen, not knowing exactly why I’m here or what I believe but wanting to do the best I can.

The man frantically points at an exploded blue hatchback just past our checkpoint. I can’t understand him, but he’s insistent, so I get our translator. The man says the blue hatchback is his brother’s car, and his brother has been missing for a couple days, so we allow him through the checkpoint. When the man gets to the car, his fears are confirmed. His brother is in two pieces, blown in half just above the hip. His torso lies face down and would be choking on sand if his lungs could still draw breath. His lower spine and blood-crusted legs are still plastered to the driver’s seat.

There are also two skeletons in the car, picked so clean by fire they look almost as if they’ve never been anything but bone, one in the passenger’s seat, and one in the back. A layer of glossy fat fused to the seat backs confirms that they were once something more substantial. The two skeletons are the man’s mom and dad.

When the bear-man realizes his entire family is gone, his howls come deep and guttural. His sounds are otherworldly, a kind of grieving I’ve never heard before. He lifts his heavy-muscled arms to the sky and seems to rave at God. I can’t understand his words, but his agony pierces the limitations of language. I watch the massive man crumble, feel myself crumble. I want to lend him comfort, to extend my hand and let him feel that he is not alone. We stand meters apart, but there is a wide gulf between us. I’m just a teenager in a strange land wearing the uniform of a foreign invader. It was likely at the hands of my people that his family was destroyed. Duty pulls me one direction, compassion another. Half of my heart goes with my body as I deal with the swelling crowd—we can’t lose control, can’t add violence to violence—half stays with the man as he scoops his family into a wooden box.

***

My team drives up to the bank in time to see the remains of Stanley’s attacker on the road. From the turret, I peer down on this ruined man, shattered bones jutting out at irregular angles, fragments of skull and grey matter in the concrete gutter, puddle of blood coagulating underneath him. I scan the crowd of Iraqis walking by for threats. We’re on a busy street in the middle of town, dozens of men and women skirting by. I’m always uneasy in crowds. I know that enemy gunmen use them as shields, make us choose whether or not to fire back. But even with that in the back of my mind, I’m fascinated by the men and women walking by. I watch their eyes, see how they respond to the mutilated man next to me on the ground. Most pretend he doesn’t exist. A few let their eyes flicker toward the body but quickly force themselves to look straight ahead again. They’re curious, but also highly aware I’m watching them over my machine gun. I watch one woman pass with two small children, each no more than five or six years old. She’s cloaked from head to toe in black, her eyes the only visible part of her face. I remember the franticness in her eyes, how they bulged wide and white as she looked anywhere but at the corpse and gore, hurrying her children past me and the body, pushing their little faces forward every time their eyes began to wander.

Two Marines pick up the body and throw it inside a wall around the bank. Another Marine grabs a bucketful of water and sloshes it across the pavement where the body was, rinsing away the brains and blood and pieces of skull. It’s all so matter of fact, like washing away drippings from a torn sack of garbage. The callousness claws at my insides. I want to double over, wrap my arms around my chest and shield myself from feeling what I’m feeling, but there’s nothing for it. I put my eyes back on the passing crowd and scan for threats.

***

I’m on night watch, leaning against the cool steel rim of my turret, one hand resting on the butt stock of my M240G. The wind blows softly at my face, refreshing me after many hours in the desert sun. This is early in the war, and we expect chemical attacks, so we spend every minute of every day in charcoal-lined chemical suits. The suits are heavy and oppressive. They’re meant to keep things out, not let air in, and in our full combat gear in the sun we sweat and sweat until the sun goes down and the desert chill gives us a few hours reprieve.

The night is quiet. We’re at a crossroads in a small town with a row of locked up automotive shops behind us. Stacks of unattended tires bracket us on each side. We haven’t seen a soul, Iraqi or American for hours. The rustle of sleeping Marines kicking at their Bivy sacks in the dirt is the only sound interrupting the night.

I’ve been on watch about an hour when an infantry operation begins several miles from our position. A nearby battery of artillery joins in, thumping along in deep rhythmic support. The concussion blast from each round cuts through the stillness, cuts through me. My chest pounds in unison with every round launched into the deep black sky, rocket-assists trailing fire until they get too high to see. I listen to the expectant pause in the night waiting for impact. This is my first time around artillery. I’m used to machine guns and rifles. I’m used to seeing my rounds impact almost immediately. Waiting for artillery is intolerable. At ten seconds, I wonder if something went wrong. At twenty seconds, I wonder if the rounds shoot so far I can’t hear them land. Then rolling thunder cascades across the desert, and I know the rounds found their mark.

Shortly after the artillery starts, a squad of Cobras swoops in—attack helicopters, invisible in the night, but distinct in sound. Their blades make them sound angry as they whip through the air. In the daylight, Cobras are intimidating, the way they angle forward, scanning the ground for something to kill. At night they are devastating, streaking barrages of hellfire missiles erupting out of the dark, punishing into submission whatever lives and breathes on the other end.

The attack continues into the night. I’m too far away to see the ground fighting but I continue to feel the explosions. I swing my legs over the side of the turret and onto the roof of the Humvee. The cold metal presses against the backs of my legs as I slide off the roof onto the ground and gently shake awake my replacement. After he throws on his boots, I lay down on my bag in the dirt, close my eyes, and let the explosions wash over me. I feel so calm, so at peace as the assault rages into the night. There is so much firepower around me I feel like nothing can touch me, while a few miles away, a terror is being unleashed in the lives of other human beings that at the time I can’t much understand.

***

The dead body in the bank becomes a part of daily life. When no one comes to claim it, we leave it festering in the sun. Whenever a Marine goes inside the abandoned bank to piss or find a safer place to eat, they walk past the body. A few guys decide to stop...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.1.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-8219-8 / 1667882198 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-8219-2 / 9781667882192 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,8 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich