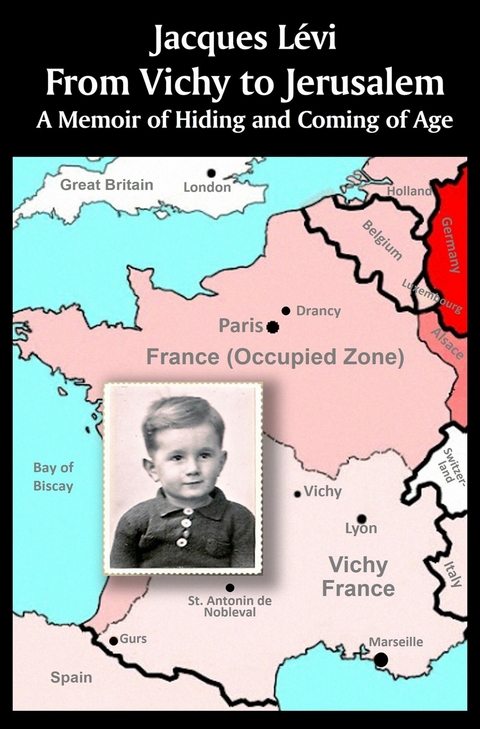

From Vichy to Jerusalem (eBook)

160 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-6135-7 (ISBN)

The first chapter of Jacques Levi's "e;From Vichy to Jerusalem"e; sets the stage and outlines the historical context of his first 3 years of life. Soon after he is born, Walter and Hilde (his father and mother), refugees from Hitler's Germany, have to reckon with Germany's invasion of France and the inauguration of a collaborationist Vichy regime in Southern France. Fears quickly escalate as anti-Semitic Vichy laws go into effect. Jews who sought refuge in France from Germany are among the first to suffer; they are persecuted and interned in French camps, sending the Levi' family into hiding. The family owes its survival to righteous individuals and families who kept their secret, who helped them live, and kept them safe. Jacques' story includes childhood memories of this time, fleshed out with the help of his parents' memories. He speaks of his growing understanding of the Holocaust history, the backdrop of war and cruelty and terror in which his life unfolded. Even as he faces his emergent understanding of France's participation in the Holocaust, Jacques is quintessentially French for most (if not all) of his life. He retains his love of French culture and literature even after emigrating to Israel. Of events after coming out of hiding and the war's end, Jacques tells how his mother and father experienced a true liberation, the freedom from terror and the freedom to begin life anew, which they did in Lyon, France. Jacques is soon at an age when he can, from his own memories, detail his early school experiences, describing his friends and teachers (complete with class pictures). Jacques fills us in on his relationship with his Mom and Dad and their family friends. Those relations are sometimes tense, especially with his father, especially so as he makes decisions (or as decisions are urged upon him) about life after high school. The tensions follow him through higher education at a prestigious school in Paris and beyond. Nevertheless, it is through his schooling and school friendships that his awareness of the contradictions between being Jewish and being French slowly come into focus. It is then that he begins to reevaluate France, to find and appreciate his Jewish roots. This leads him to a wish to know more about Israel. This leads him to meeting his wife-to-be, a family and, to life in Israel. None of this is without tribulations, which Jacques confesses with great honesty. He takes us though these latter years to their denouement.

My Grand Parents

If I hardly knew my maternal or paternal grandparents, the fault lies with the advent of Nazi fascism which swept away so many nuclear families in its path, either by destroying them or separating and dispersing their members to the four corners of the earth.

My maternal grandparents were Grete Isaac (diminutive of Margarete), born 9/1/1888, and Josef Rudolf Isaac, born 26/6/1883. Grete was from Bad Dürkheim and Josef came from Wallertheim, both towns in the Rhine Palatinate region of southern Germany.

My maternal grand-parents, Grete Isaac and Josef Isaac, with their nephew

Fritz Wolf

Oma Grete (Savta) is buried in my hometown of Dijon in a tomb that she shares with a foreigner. At that time in 1941 Mum was living alone and did not have enough money to ensure her a separate burial. Mum gave me a portrait of a woman who was not very happy, no doubt because of the marriage of convenience with my grandfather Josef Isaac, into which she had been forced. Opa Josef was an authoritarian who tyrannized over her and whom she feared. Oma’s father Gustave, my great-grandfather, was away from home constantly and he died prematurely at the age of 54. While he lived, he hardly looked after his two children (Oma Grete and her brother Arnold). His wife Marie Wolf, my great-grandmother (I refer to her also as Oma…, as Oma Wolf) had always shown a preference for her eldest son Arnold, leaving Oma Grete to feel less preferred, less than special. Grete had become a French teacher, a profession that she chose after a one-year stay in Paris before her marriage. In her relations with her only daughter Hilde, a child and then a teenager, she was a stern and very strict mother, attaching excessive importance to order, discipline and impeccably done homework.

Already handicapped by asthma (which I inherited), Grete died of cancer, too young and in great pain at age fifty-three, in our apartment in Dijon in February 1941. Her illness was just the outward, somatic expression of the moral suffering inflicted by the previous eight years (1933-41), starting with the daily persecutions in Nazified Germany, followed by the misery caused by forced exile and the theft of family patrimony. Add to these the feeling of being uprooted in a foreign land, the absence of any prospect leading to security, and the anguish of seeing all her family…, her husband , her only daughter, her son-in-law and her only grandson, me, having to face a cruel fate that threatened to swallow them at every moment. It takes little imagination to realize how she must have suffered.

In early 1939, already stripped of most of their property, my grandparents had pooled with other members of their family the little money the Germans had left them to buy an agricultural property in Morsbach, in Lorraine, just across the Franco-German border. They must have deluded themselves into thinking that the Hitler phenomenon was temporary and that they would return home soon. As fortune would have it, a year later in June 1940, this region was annexed by the German invader and the family was driven further into France, ending up without any means of existence whatsoever at St. Genis d’Hiersac in the Charente department, near Angoulême in southwestern France. The events of the last years had overcome Oma Grete’s moral resistance and triggered the cancer diagnosed in a Parisian hospital. It was Mum with me on her arms, who took her to the hospital towards the end of 1940. As I write these words, I want to tell Oma Grete now of all the love and affection I would have given her then if she had survived. I know from Mum that Oma and I shared a taste for study, books, and art. I lost in her, besides the Grandma I so badly needed, a cultural guide of choice.

Her husband, Opa Josef (Opa “Fofef”, as I am told I called him at the age of two or three) survived her by about a year. As portrayed to me by Mum, Opa was short in stature, self-taught, a brilliant conversationalist, much appreciated in society, but feared in his own home where he wielded undivided authority. No doubt disappointed that he had but a daughter as his only child, he had always considered Mum to be inconsequential. As a result, their relationship was never very warm. On the other hand, he had felt the keenest sympathy towards my father, with whom he must have found much in common. But Papa also knew how to command respect. As a result, it happened one day after Opa Josef had spoken to Mum, yet a young bride, in the harsh tone that he was accustomed to use when she was only his daughter, my father sharply rebuked Opa, pointing out to him that it was past time to address and treat “Walter Lévi’s wife” with all the respect due her new status. In the short time he that knew me, Opa vowed to Maman (according to her) “to treat me with the greatest reverence”. Dear Opa, even as a child I missed you, though I did not understand the reason or significance of your premature disappearance…

We had withdrawn to Lyon to be in the so-called free zone. But Lyon was in turn also occupied by the Germans at the end of 1942. Thereafter, the French police were charged by the Vichy regime to roundup and intern all foreign Jews in transit camps, then to be sent on to the Nazi extermination machine. My unfortunate Opa Josef was persuaded by a Jewish doctor that he could escape these roundups by being ‘hospitalized’ at Lyon’s Grange Blanche Hospital. It was therefore in this hospital that he was arrested by the French police or the Milice Française (a special French police force working closely with the Gestapo) and directed to Drancy, just north of Paris, the anteroom of the extermination camps. He was then dispatched on the March 4, 1943, by convoy no. 50 to Majdanek or Sobibor… where he was undoubtedly gassed upon his arrival. He was not sixty years old. The doctor who proffered the unfortunate advice was also deported.

I was too young when my maternal grandparents passed away; I do not remember the slightest bit. Everything I know about them was told to me by my parents. It is clear to me that by murdering my maternal grandparents (Oma Grete’s cancer was another form of murder), the Germans deprived me of much of the precious affection which makes all little children happy.

As for my paternal grandparents Isaac and Emilie Lévi, I hardly knew them at all. By the time I was born, they had obtained an “affidavit” (permit) to enter the United States and had finally resolved (almost at the last moment) to leave Germany, the country that was driving them away, robbing them of the possessions amassed during a lifetime of hard work, and depriving them of some of their children and their respective families.

Seated: left, Emilie Lévi (Oma Lévi, also called Oma Emilie, my paternal grand-mother); right, Isaac Lévi (Opa Isaac, my paternal grand-father); middle, Walter Lévi, to be my father (around 1929)

They came to take leave of us in Dijon just before their departure, which took place a few weeks after my birth. Mum especially remembers that Opa Isaac had blessed all three of us, putting his whole soul into this blessing, aware as he was of the coming cataclysm. Like so many others, he must have known that Hitler was about to send Europe up in flames and that Divine Providence would not be enough to save us from the fires on the horizon. Mum has thought about Opa Isaac’s blessing many times since and likes to believe it was heard in high places.

When I truly made their acquaintance thirteen years later at my Bar-Mitzva (first communion in Hebrew), I saw in front of me a pair of old foreigners with whom I do not remember having exchanged so much as three words during their presence among us. My Oma Emilie was already suffering dementia. Of course, they were lucky to have survived, but Hitler had stolen everything from them: their possessions, their past, their roots, their full life in a pre-1933 Germany that they had loved before the Fuehrer’s savage theft. Dear Opa and Oma, I want to tell you how much I would have liked to have known you, how I would have accepted and now return your affection. I miss what would have been your advice and your encouragement in the difficult moments of my childhood and then of my adolescence.

Sometimes I like to imagine that you, my five most familiar ancestors, Marie Wolf (my maternal great-grandmother, who knew me until the age of 5); Opa Isaac, and Oma Emilie; and Opa Josef and Oma Grete…, since you are no longer, and precisely because you could not take your place as my grandparents…, I imagine that you have obtained by way of compensation, the celestial power to be our guardian angels. The more I reflect on my existence and the various critical hazards of life that I passed through and from which I came out surprisingly unscathed, the more I feel that a protective and compassionate hand has brushed aside brambles and thorns or thrown a bridge over the chasms that threatened to engulf us. Perhaps without knowing it, I have from my ancestors the magic flute that their past merits have earned them. Or quite simply, if not a protective flute, then I have endured my ordeals because in the end, they existed.

Here now is what happened to Mum and Dad in the fall of 1939. In the days that followed the absurd declaration of war by France on Germany on September 3, the French army followed its defensive (and therefore its defeatist) strategy, limiting itself to waiting...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.1.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-6135-2 / 1667861352 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-6135-7 / 9781667861357 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,6 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich