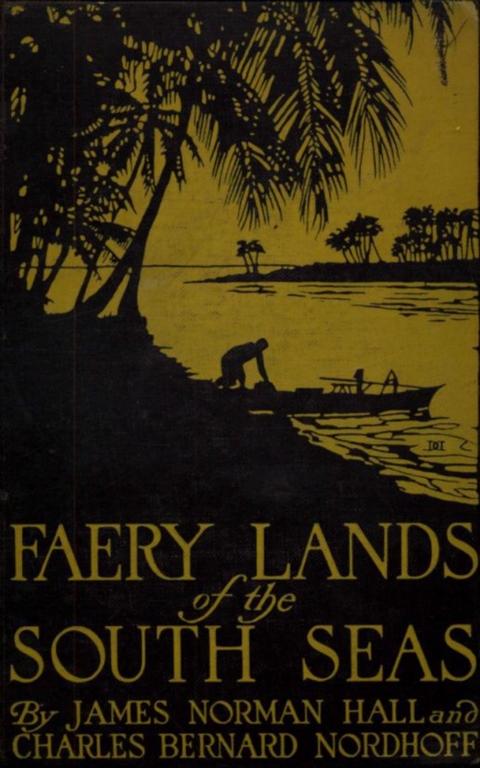

Faery Lands of the South Seas - James Norman Hall, Charles Bernard Nordhoff (eBook)

569 Seiten

anboco (Verlag)

978-3-7364-1907-0 (ISBN)

He was not able to figure it out in this case. The old woman was talkative; but the information he gathered from her only stimulated his curiosity the more. She owned Tanao, an atom of an atoll miles out of the beaten track even of the Paumotu schooners. There had never been more than a score of people living on it, she said, and now there was no one. Crichton had taken a long lease on it, and was going out there—as he told me afterward—"to do my writing and thinking undisturbed."

I didn't know this until later, however. When I first heard him spoken of we were only a few hours out from Papeete. We had left the harbor with a light breeze, but at four in the afternoon the schooner was lying about fifteen miles offshore, lazy jacks flapping against idle sails with a mellow, crusty sound. After a good deal of fretting at the fickleness of land breezes, talk had turned to Crichton, who was up forward somewhere looking after his chickens. I didn't pay much attention then to what was being said, for I had just had one of those moments which come rarely enough in a lifetime, but which make up for all the arid stretches of experience. They give no forewarning. There comes a flood of happiness which brings tears to the eyes, the sense of it is so keen. The sad part of it is that one refuses to accept it as a moment. You say, "By Jove! I'm not going to let this pass!" and it has gone as unaccountably as it came, half lost through foreboding of its end. One prepares for it unknowingly, I suppose, through months, sometimes years, of longing for something remote and beautiful—such as these islands, for example. And when you have your islands, the moment comes, sooner or later, and you see them in the light which never was, as the saying goes, but which is the light of truth for all that. Brief as it is, no one can say that the reward isn't ample. And it leaves an afterglow in the memory, tempering regret, fading very slowly; which one never wholly loses since it takes on the color of memory itself, becoming a part of that dim world of worth-while illusions.

All of which has very little to do with what was passing aboard the Caleb S. Winship, except that I was prevented from taking an immediate interest in my fellow passengers; but this being my first near view of a Polynesian trading schooner, the scene on deck had all the charm of the unusual. Our skipper was a Paumotuan, a former pearl diver, and the sailors—six of them, including the mate—Tahitian boys. In addition to these there were Crichton, the planter; the supercargo, master of three major languages and half a dozen Polynesian dialects; the manager of the Inter-Island Trading Company; William, the engineer; Oro, the cabin boy; a Chinese cook and two Chinese storekeepers—evidence of the leisurely, persistent Oriental invasion of French Polynesia; thirty native passengers; a horse in an improvised stall amidships; a monkey perched in the mainmast rigging; Crichton's four crates of chickens, and five pigs. In addition to the passengers and live stock, we were carrying out a cargo of lumber, corrugated iron, flour, rice, sugar, canned goods, clothing, and dry goods. Each of the native passengers brought with him as much dunnage as an Englishman carries when he goes traveling, and his food for the voyage—limes, oranges, bananas, breadfruit, mangoes, canned meat. With all of this, a two months' supply of gasoline for the engines, and fresh water and green coconuts for both passengers and crew, we made a snug fit. Even the space under the patient little native horse was used to stow his fodder for the long journey.

The women, with one exception, were barefooted, bareheaded, but otherwise conventionally dressed according to European or American standards. This, I suppose, is an outrageous betrayal of a trade secret, if one may say that writers of South Sea narratives belong to a trade. Those seriously interested in the islands have, of course, known the truth about them for years; but I believe it is still a popular misconception that the women who inhabit them—no one seems to be interested in the men—are even to this day half-savage, unself-conscious creatures who display their charms to the general gaze with naïve indifference. Half-savage they may still be, but not unself-conscious in the old sense. There are a few, to be sure, who, by means of the bribes or the entreaties of itinerant journalists and photographers, may be persuaded to disrobe before the camera for a moment's space; and in this way the primitive legend is preserved to the outside world. But, as I told Nordhoff, although we are itinerant, we may as well be occasionally truthful and so gain, perhaps, a certain amount of begrudged credit.

The one exception was a girl of about nineteen. She came on board balancing unsteadily on high French heels, her brown legs darkening the sheen of her white-cotton stockings. I had seen her the day before as she passed below the veranda of Le Cercle Bougainville, the everyman's club of the port. She walked with the same air of precarious balance, and her broad-brimmed straw hat was set at the jaunty angle American women affect.

"Voilà! L'indigène d'aujourd'hui," my French companion said. Then, breaking into English: "The old Polynesia is dead. Yes, one may say that it is quite, quite dead." A memory he called it. "Maintenant je vous assure, monsieur, ce n'est rien que ça." He rang changes on the word, in a soft voice, with an air of enforced liveliness.

I was rather saddened at the time, picturing in my mind the scene on the shore of that bright lagoon two hundred years ago, before any of these people had been forced to accept the blessings of an alien civilization. But the girl with the French heels wasn't a good illustration of l'indigène d'aujourd'hui, even in the matter of surface changes. Most of the women dress much more simply and sensibly, and it was amusing as well as comforting to see how quickly she got rid of her unaccustomed clothing once we had left the harbor. She disappeared behind a row of water casks and came out a moment later in a dress of bright-red material, barefooted and bareheaded like the rest of them. She had a single hibiscus flower in her hair, which hung in a loose braid. I don't believe she had ever worn shoes before. At any rate, as she sat on a box, husking a coconut with her teeth, I could see her ankle calluses glinting in the sun like disks of polished metal.

There was another girl sitting on the deck not far from me, with an illustrated supplement of an American paper spread out before her. It was an ancient copy. There were pictures of battlefields in France; of soldiers marching down Fifth Avenue; a tennis tournament at Longwood; aeroplanes in flight; motor races at Indianapolis; actresses, society women, dressmakers' models making a display of corsets and other women's equipment—pictures out of the welter of modern life. The little Paumotuan girl appeared to be deeply interested. With her chin resting on her hands and her elbows braced against her knees, she went from picture to picture, but looked longest at those of the women who smiled or posed self-consciously, or looked disdainfully at her from the pages. I would have given a good deal to know what, if anything, was passing in her mind. All at once she gave a little sigh, crumpled the paper into a ball, and threw it at the monkey, who caught it and began tearing it in pieces. She laughed and clapped her hands at this, called the attention of the others, and in a moment men, women, and children had gathered round, laughing and shouting, throwing bits of coconut shell, mango seeds, banana skins, faster than the monkey could catch them.

The spontaneity of the merriment did one's heart good. Even the old men and women laughed, not in the indulgent manner of parents or grandparents, but as heartily as the children themselves. Unconscious of the uproar, one of the Chinese merchants was lying on a thin mattress against the cabin skylight. Although he was sound asleep, his teeth were bare in a grin of ghastly suavity, and his left eye was partly open, giving him an air of constant watchfulness. He was dreaming, I suppose, of copra, of pearl shell—in kilos, tons, shiploads; of its market value in Papeete, in San Francisco, in Marseilles, etc. Well, the whites get their share of these commodities and the Chinamen theirs; but the natives have a commodity of laughter which is vastly more precious, and as long as they do have it one need not feel very sorry for them.

Dusk gathered rapidly while I was thinking of these things. Heavy clouds hung over Tahiti and Moorea, clinging about the shoulders of the mountains whose peaks, rising above them, were still faintly visible against the somber glory of the sky. They seemed islands of sheer fancy, looked at from the sea. It would have been worth all that one could give to have seen them then as De Quiros saw them, or Cook, or the early missionaries; to have added to one's own sense of their majesty, the solemn and more childlike awe of the old explorers, born of their feeling of utter isolation from their kind with the presence of the unknown on every hand. It is this feeling of awe rarely to be known by travelers in these modern days, which pervades many of the old tales of wanderings in remote places; which one senses in looking at old sketches made from the decks of ships, of the shores of heathen lands.

The wind freshened, then came a deluge of cool water, blotting out the rugged outlines against the sky. When it had passed it was deep night. The forward deck was a huddle of shelters made of mats and bits of canvas, but these were being taken down now that the rain had stopped. I saw an old woman sitting near the companionway, her head in clear relief against a shaft of yellow...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.6.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| ISBN-10 | 3-7364-1907-4 / 3736419074 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-7364-1907-0 / 9783736419070 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 773 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich