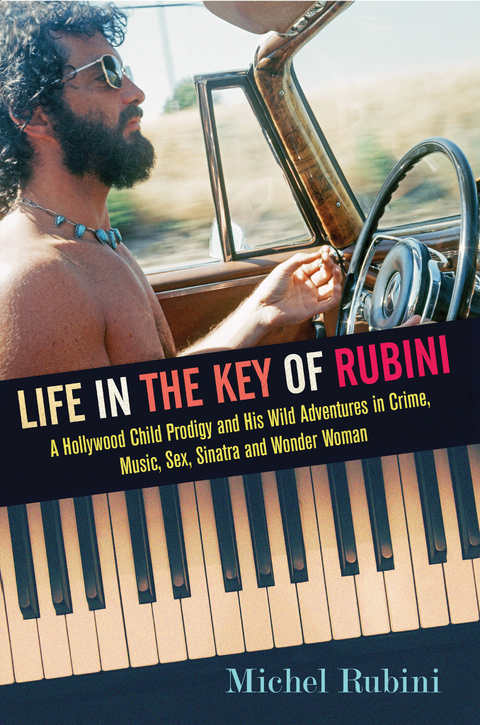

Life in the Key of Rubini (eBook)

314 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-5439-2245-5 (ISBN)

Life in the Key of Rubini is a high-flying, heartfelt, and gripping memoir about Michel Rubini's days of hit-making, hell-raising, and skirt-chasing within a Hollywood music scene long gone. Between playing on smashes such as "e;Strangers in the Night,"e; "e;I Got You Babe,"e; and "e;Unchained Melody"e; to involvements with gorgeous film and TV performers such as Raquel Welch, Joanna Moore, and Lynda Carter (i.e. Wonder Woman), the evidence is clear: Michel Rubini has led the kind of life that few could ever imagine. The classically-trained son of a world-famous violinist and a Hollywood actress, the free-spirited Rubini became the very personification of the Swinging Sixties. With off-the-chart piano-playing skills, movie-star good looks, and a rakish, devil-may-care attitude, his success as part of the legendary Wrecking Crew session musicians only equaled his astonishing appeal among a very willing portion of the female population. For a remarkable period, seemingly few gold records were recorded in LA without him and even fewer starlets were able to resist him. As the saying goes, there are two great days in every person's life: the day they are born and the day they discover why. Unlike most, however, Michel Rubini has always known exactly why he was born.

Four

Practice Time, Not Play Time

My parents first noticed my unusual ability to organize notes on the piano when I was about three years old. At the time, we were staying in Australia, where my father headlined at one of the big vaudeville theatres that were so popular there during the mid-to-late 1940s. After witnessing my precocious keyboard skills, he and my mom decided they would start me on piano lessons when we returned to the United States.

In that regard, we were fortunate to live next door in Malibu to a lovely little old lady piano teacher named Peg Thompson. She started me off with the standard fare that all young students learn: scales, finger exercises, and simple pieces such as “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” We bought the books, I started to practice, and I moved along quite rapidly. In fact, I excelled much more quickly than my teacher had anticipated, taking her by surprise. She was confused by the way I was progressing because it wasn’t the normal way of doing things. I was not advancing in my scales and exercises nearly as fast as I was in the songs she assigned me, which in her world made no sense. Scales and exercises, though tedious, are the building blocks students usually need to practice over and over in order to (hopefully) play ever more complex passages. But I didn’t need to do all that because I had a secret weapon: my perfect pitch.

You see, I was not practicing my scales and exercises much because I hated them. Instead, I was able to memorize and play the pieces quite easily because I would simply watch her play them for me at each lesson. Between watching her fingers and listening carefully, I could repeat any given piano passage almost without mistakes. What I was not doing was practicing my reading like I should have, so really I was already trying to find the easy way out rather than sitting down and doing the hard work necessary to become a real pianist.

Much to my chagrin, my little attempt at subterfuge did not go on for long, though, because Mrs. Thompson was much smarter than I thought. She went to my mother and told her that I was a gifted but difficult student because of my perfect pitch and, if they were serious about having me become a proper pianist, they were going to have to make me really practice. Further, my teacher said that I needed a stricter and stronger instructor than she, a teacher capable of really challenging and controlling me. So she recommended Mr. Herman Wasserman, if he would accept me as a student that is. Thus, my little ruse and easy times came to an abrupt end.

Known as the finest piano teacher in all of Los Angeles and arguably the entire country, Wasserman had taught pianists and compositional luminaries Ferde Grofé and George Gershwin. He even edited and fingered all of Gershwin’s songbooks, too. Needless to say, Wasserman was the real deal. I started lessons and studied with him until I was fourteen and a half (when he suddenly died). But those years under his tutelage were the most critical in my development and set me on a path for life. I could never have thanked him enough, and when he died, I stopped playing piano for almost a year and a half.

From the beginning, Wasserman taught me the most important thing anyone could ever learn from his or her teacher: how to teach yourself. He knew he wouldn’t be alive forever and that every great pianist, myself included, must eventually develop the ability to teach himself. Otherwise, how would that person—just like Arthur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz, who both ceased having piano teachers long before they became world famous—possibly continue to grow as a skilled musician into adulthood and beyond?

So, with my subsequent reassignment to Mr. Wasserman, I began my real and many hard years of pure drudgery, being forced by my mother to practice at least one, and often up to two and half, hours every day. One hour before breakfast and school and then at least one hour after school and before dinner. If I didn’t get in at least an hour of practice before school, then my mom made me add that to the hour after school. To make matters worse, she made it a habit to sit right next to me on the piano bench for the hour after school and watch me practice. She could read music, so when I made a mistake or began faking it, she would stop me and make me do it again until I got it right.

There was something else my mother did that was particularly painful to me. Being born of good, strong Norwegian stock and therefore having powerful hands and arms, she learned a trick (I don’t know from whom) that she performed with the knuckle on the third finger of her left hand; she called it her Norwegian fist. Making her fingers into a ball, but sticking out the third knuckle about an inch, she would jam that into the middle of my ribs every time I started to slouch over the keyboard. “Sit up straight,” she would command, and believe me I did. I learned early on that I had better do as she said or risk paying for it with some very hard Norwegian knuckle sandwiches.

Since I had to practice every day after school, I hardly ever got to go outside and play with the other kids. There was a big, vacant parking area right across the street from our house where the neighborhood kids gathered to play kickball until dark when they had to go home and eat dinner. We all got off the school bus at the same time, but I was the only one who had to go in the house. There, I would have a fast sandwich and then march over to the piano and practice, while outside, all the other kids would be having fun and kicking their ball all over the place. Sometimes I would walk up to the front gate and look wistfully across the street at the children for a minute or two. But my mom would invariably call me back into the house and tell me that if I finished my practice soon enough I could go out and play with them. Except, the only problem was that it always got dark or dinner was about to be served by the time I finished practicing, so I never got to go out and play with them, other than sometimes on the weekends. Those were my first few years of learning to play the piano in a nutshell.

Now, while I was learning my scales, exercises, and pieces, my father had another idea. He thought it would be just grand if I started to learn some of the accompaniments to his concert violin pieces. Not the hard ones, you understand, at least by his standards. Just the easy ones, like Träumerei by Schubert, which most adults couldn’t even come close to playing. Dad thought it would be fun to trot me out at his parties and receive the accolades for being the father of such a talented young son. Now believe it or not, this really wasn’t much of a stretch for me even at that age—I was only six —because I had been hearing these pieces ever since I was born. I already knew them in my mind; I had just never played them. But when my father put the music in front of me, all I had to do was to look at the notes to learn the routine and exact fingering, etc. And from there, I was playing them in no time.

By the time I was eight or nine, I was playing most of Dad’s repertoire almost as well as his regular professional accompanist. By the time I was fourteen, I had become his regular accompanist. He replaced his old friend and longtime piano player, a gentleman who had been by his side for about twenty years, and instead started using me for all his shows. As long as they were in the Los Angeles area and did not interfere with my schooling, that is (my mother saw to that). I’m sure I saved my dad thousands of dollars in accompanist fees and in return received nothing more than my regular allowance that started at twenty-five cents a week. When you think about it, it gives new meaning to the phrase “child labor,” doesn’t it?

But there were lots of concerts that I did not play when they were held out of town. In particular, there was one trip I wanted to go on very badly, but my mom put her foot down and said absolutely not, not under any circumstances. And that was my father’s last trip to South Africa in 1952. He had a tour set up there, and he ended up being gone for six months straight, performing over there to sold-out theatres every night, and during the days going on safari to see the lions and giraffes and Zulu warriors in an adventure I could only dream about. Being ten years old at the time and crazy about wild animals and far away places like Africa, I cried and begged my mom to distraction to let me go, but she wouldn’t hear of it. There would be no missing school for me. My father would just have to pay his regular guy to go with him and leave me home. No fun at all, I tell you.

However, all the enforced isolation and practice paid off in the long run, because by the time I was sixteen, I became my father’s regular accompanist and even dropped out of high school...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.4.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5439-2245-7 / 1543922457 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5439-2245-5 / 9781543922455 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 23,1 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich