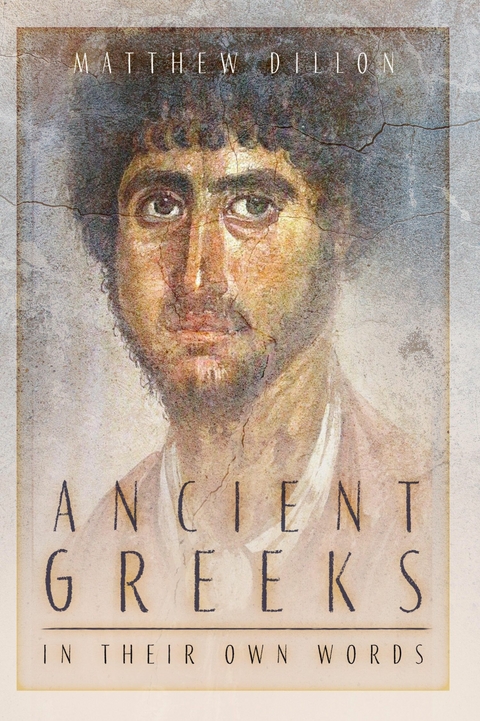

Ancient Greeks in Their Own Words (eBook)

324 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-874-9 (ISBN)

MATTHEW DILLON teaches classics at the University of New England in New South Wales, Australia.

Introduction

Man is but the dream of a shadow.

Pindar, Pythian Victory Ode, 8.95–6.

Pindar immediately arrests our attention here, drawing us towards a consideration of the ancient Greeks, and in a few words beckoning us towards their contemplation of the human spirit and its potential. Materially their temples are able even in their ruined state to speak to us about their religious aspirations. But their words reveal much more, defining the human spirit and speaking eternal truths.

Ancient Greece was the crucible of western civilisation. Most of what is known about the ancient Greeks comes from their writings, particularly in the archaic and classical periods, which lasted from about 800 BC to 336 BC. Archaeology is important, particularly when it yields the remains of houses, domestic items, works of art, graves and inscriptions. But on the whole it is writers such as Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon who provide the history of this period, with poets such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Pindar and Bacchylides revealing the ethos and customs of the Greeks.

Many of these writers were conscious of their own abilities. Thucydides wrote that his work was destined for posterity, to last for all time, while Pindar says of himself, Fragment 152: ‘My voice is sweeter than honey-combs toiled over by bees.’ There can be no better way to learn about the Greeks than by reading what they wrote about themselves: what concerned them most, what behaviour they found acceptable (and what unacceptable), what interested them, what they feared and what pre-occupied them.

But who were the ancient Greeks? Ancient Greece consisted of the Greek mainland itself, as well as Crete and the Aegean islands, just as it does today. But in addition the Greeks had in two main waves of colonisation spread elsewhere. From about 1200 to 1000 BC, the Greeks settled the coast of what is now Turkey, giving rise to magnificent cities such as Miletus, Ephesus and Didyma; the remains of these and other Greek cities are particularly impressive. There was a second wave of colonisation from about 800 to 600 BC when the Greeks settled the shores of the Black Sea, Sicily and southern Italy, with some colonies as far away as modern-day France (notably modern Marseilles) and Cyrene in Libya.

But like all societies, there were radical differences between not just various groups of Greeks but also between those living within the same city. The Greeks were not a homogenous group but lived in thousands of different communities, each recognisably Greek but also with local customs and other distinguishing features. Today, the remains of Greek temples from Naples in Italy to Ephesus in Turkey bear witness to this greater Greek world. But more than ruins are left behind. The Greeks produced the first outpouring of western literature, beginning with the poet Homer, the favourite of the Greeks themselves throughout their history. (In fact, over twenty Greek cities claimed to be his birthplace.) He and other poets believed that their works were the result of divine inspiration by the nine Muses, goddesses of poetic inspiration. The words of the Greeks included in this volume come not just from Greeks in Athens, but from those who lived in Asia Minor, on the Aegean islands, in Syracuse and Egypt. Over a cultural world several thousands of kilometres wide, they give voice to all that was best – and worst – in Greek civilisation.

Greece itself is often described as a country dominated by hills, mountains and small plains and this is true to some degree, but there is fertile soil. Thucydides wrote of the various waves of invasion of Greece, in which the best land was conquered by newcomers. Thucydides, 1.2.3, 5: ‘[1.2.3] It was always the best land that experienced changes of inhabitants, the land now called Thessaly and Boeotia, and most of the Peloponnese, except for Arcadia, and the most fertile areas of the rest of Greece . . . [1.2.5] But the area around Athens from the earliest times, because of its thinness of soil, was undisturbed and always inhabited by the same race of men.’ Sparta itself nestles in a bowl, and the snow of Mount Taygetus is visible from nearly any direction. Homer describes it in the Odyssey, 4.1: ‘Sparta lying in a hollow, full of ravines’.

In mainland Greece there are numerous mountain ranges often hemming in small or medium-sized plains. In the middle of such a plain, usually clustered around a hilly outcrop of rock, was the city. Many cities had such a centre and the Greeks called it an acropolis, of which that at Athens is an excellent example. On it stands the temple of the Parthenon, dedicated to the virgin goddess Athena; it still dominates the modern city’s skyline. And, as at Athens, the acropolis of an area was often the first place of settlement, and then as towns and cities grew, the people lived in houses clustered around its base and the acropolis became public property, where temples were built and often political meetings were held.

Ancient Greece was dominated by what is called the city-state, which the Greeks called the polis. Greece was not in any sense a ‘nation’, but rather a cultural phenomenon, something like the western European world, where there are separate governments that, however, share a common religious, political and economic heritage. The modern political building-block is the nation. In ancient Greece, its equivalent was the city-state. The polis was a small city by modern standards. There were literally hundreds of Greek cities, some of them no more than small towns. Greek city-states had their own armies, calendars, currencies and local variations on the main political systems of democracy, aristocracy or oligarchy. Different cities had different names for the months and common dating was non-existent.

Athens, with its 30,000 male citizens, was the largest Greek city-state, followed by Syracuse in Sicily, which had about 20,000 citizens. A city-state was ideally, in Greek eyes, an autonomous political unit. The city with its associated amenities was the high-point of Greek civilisation, and for the Greeks life without the city was unimaginable. Athens and Sparta were the main cities of ancient Greece, but there were many differences between them, not just physically but also in terms of temperament, characteristics and outlook.

At the conference of Sparta and its allies in 432 BC when it was debated whether to go to war or not against the Athenians, the delegates from Corinth attempted to goad the Spartans into action by unfavourably comparing them with the Athenians. The contrasts might be overdrawn but hold true on the whole: the Athenians were dynamic and resourceful, the Spartans (who never numbered more than 10,000, and this figure gradually decreased) tried to stay at home as much as possible and did not take risks, as they had a large servile population, the helots, to control. In their speech at Sparta, the Corinthians made the following points. Thucydides, 1.70.1–9:

(1.70.1) You Spartans have never considered what sort of men the Athenians are and how completely different from you are the men you will fight against. (1.70.2) They are without a doubt innovators, and quick to make their plans and to accomplish in reality what they have thought out, but you preserve simply what you have, and come up with nothing new, and in what you actually undertake don’t complete what has to be done. (1.70.3) And in addition, the Athenians are reckless beyond their capabilities, risking danger beyond their judgement, and are confident even in crises. But for you it is the case that you undertake less than your power allows, you distrust what your judgement is certain of, and think you will never escape from your crises. (1.70.4) And again, they are unhesitating while you procrastinate, they are abroad while you are the greatest ‘stay-at-homes’. They believe that by being abroad they will gain something, while you think that if you go out on campaign you will damage what you have already. (1.70.5) If they are victorious over their enemies they advance over the greatest distance, and when they are defeated give ground as little as possible.

(1.70.6) Furthermore, they use their bodies on behalf of the city as if they were somebody else’s, but their minds as most intimately their own for activities on her behalf. (1.70.7) And when they plan something but fail to achieve it they feel they have been robbed of their rightful possessions, and whenever they go after something and take possession of it, they consider they have achieved only a small thing compared with what the future will bring, and if they might fail in an undertaking, they make up for the loss by forming expectations for other things. For to them alone, having is the same as hoping in whatever they plan, due to the quickness with which they act upon their decisions. (1.70.8) At all this they labour with toils and dangers throughout their lives, and have little enjoyment of what they have as they are always acquiring more and they consider that there is no holiday except to do what has to be done, and that untroubled peace is no less a disaster than laborious activity. So if someone summing up the Athenians were to say that they were born neither to have peace themselves nor to allow it to other men, he would speak correctly.

So Athenian and Spartan characteristics were very different. In addition, the Athenians were wealthy and adorned their city with magnificent temples, such as the Parthenon mentioned above. Sparta, however, was lacking in financial resources and the modern visitor will not find any impressive remains from the classical period. But this is exactly...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Altertum / Antike |

| Schlagworte | Alexander the Great • Ancient Greece • anicent civilisations • Classical era • classic civilisations • collected biographies • Customs and Traditions • famous greeks • Greek • Greek Culture • greek life • Greek Literature • Greek poetry • Polis |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-874-1 / 1803998741 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-874-9 / 9781803998749 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich