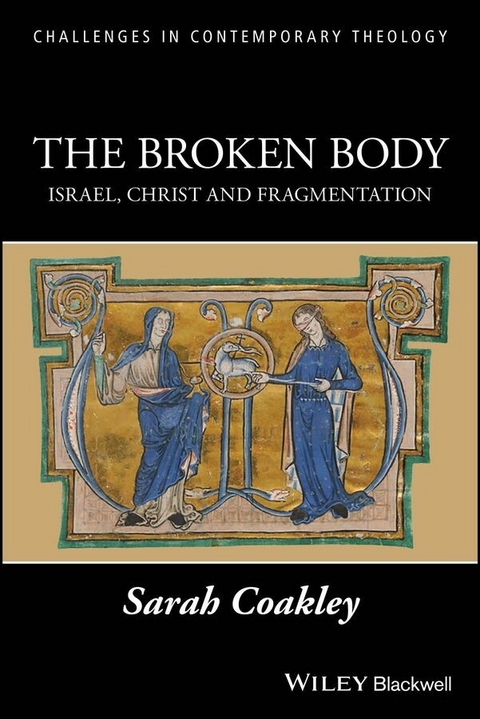

Broken Body (eBook)

336 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-118-78080-0 (ISBN)

A fascinating collection of essays exploring a fresh contemporary approach to the person and doctrine of Jesus Christ

How should Christians think about the person of Jesus Christ today? In this volume, Sarah Coakley argues that this question has to be 'broken open' in new and unexpected ways: by an awareness of the deep spiritual demands of the christological task and its strikingly 'apophatic' dimensions; by a probing of the paradoxical ways in which Judaism and Christianity are drawn together in Christ, even by those issues which seem to 'break' them most decisively apart; and by an exploration of the mode of Christ's presence in the eucharist, with its intensification,' breaking' and re-gathering of human desires. In this sequel to her celebrated earlier volume of essays, Powers and Submissions, Coakley returns to its unifying theme of divine power and contemplative submission, and weaves a new web of christological outcomes which remain replete with controversial implications for gender, spirituality and ethics.

The Broken Body will be of interest to those working in the fields of systematic theology, philosophy of religion, early Christian studies, Jewish/Christian relations, and feminist and gender theory.

'Fusing biblical and patristic theology, analytic philosophy, and spiritual tradition, Sarah Coakley has produced a fascinating, inspiring, and compelling account of Christ's identity, and its importance for questions of life.' Professor Mark Wynn, University of Oxford

'Coakley argues that good Christology arises only from intellectual and spiritual postures learnt by encountering Christ openly. This volume subtly and powerfully facilitates such encounter, with God and, in him, with our neighbours, especially the Jewish people.' Professor Judith Wolfe, University of St. Andrews

'Everything we have come to expect from Sarah Coakley is here in this extraordinary collection: wonderful clarity; startling and fruitful comparisons, within and beyond the theological canon; a brisk defiance of feminist conventions that in turn sharpens and deepens feminist analysis; a resistance to cheap theological certainties; and an abiding faithfulness, anchored in Christ, borne aloft by the Spirit. Christology is here shown to embrace abjection and jouissance, to advocate sacrifice that is itself the end of patriarchal violence, and to demand a eucharistic sharing that is incomplete without solidarity to the outcast and the poor, themselves the face of the living Christ. In these essays Coakley exemplifies the semiotic richness of priest and scholar, a breaking open of theological reserves that will transgress, startle, renew, instruct. This is sacrifice, re-made.' Professor Katherine Sonderegger, Virginia Theological Seminary

Sarah Coakley, FBA is the Norris-Hulse Professor of Divinity emerita, University of Cambridge, and an honorary Professor of St Andrews University and of the Australian Catholic University (Melbourne and Rome). Amongst her previous publications are Powers and Submissions; God, Sexuality and the Self; The New Asceticism; and the Gifford Lectures of 2012, Sacrifice Regained: Evolution, Cooperation and God. She is currently at work on the remaining volumes of her systematic theology.

A fascinating collection of essays exploring a fresh contemporary approach to the person and doctrine of Jesus Christ How should Christians think about the person of Jesus Christ today? In this volume, Sarah Coakley argues that this question has to be 'broken open' in new and unexpected ways: by an awareness of the deep spiritual demands of the christological task and its strikingly 'apophatic' dimensions; by a probing of the paradoxical ways in which Judaism and Christianity are drawn together in Christ, even by those issues which seem to 'break' them most decisively apart; and by an exploration of the mode of Christ's presence in the eucharist, with its intensification, 'breaking' and re-gathering of human desires. In this sequel to her celebrated earlier volume of essays, Powers and Submissions, Coakley returns to its unifying theme of divine power and contemplative submission, and weaves a new web of christological outcomes which remain replete with controversial implications for gender, spirituality and ethics. The Broken Body will be of interest to those working in the fields of systematic theology, philosophy of religion, early Christian studies, Jewish/Christian relations, and feminist and gender theory. "e;Fusing biblical and patristic theology, analytic philosophy, and spiritual tradition, Sarah Coakley has produced a fascinating, inspiring, and compelling account of Christ's identity, and its importance for questions of life."e; Professor Mark Wynn, University of Oxford "e;Coakley argues that good Christology arises only from intellectual and spiritual postures learnt by encountering Christ openly. This volume subtly and powerfully facilitates such encounter, with God and, in him, with our neighbours, especially the Jewish people."e; Professor Judith Wolfe, University of St. Andrews "e;Everything we have come to expect from Sarah Coakley is here in this extraordinary collection: wonderful clarity; startling and fruitful comparisons, within and beyond the theological canon; a brisk defiance of feminist conventions that in turn sharpens and deepens feminist analysis; a resistance to cheap theological certainties; and an abiding faithfulness, anchored in Christ, borne aloft by the Spirit. Christology is here shown to embrace abjection and jouissance, to advocate sacrifice that is itself the end of patriarchal violence, and to demand a eucharistic sharing that is incomplete without solidarity to the outcast and the poor, themselves the face of the living Christ. In these essays Coakley exemplifies the semiotic richness of priest and scholar, a breaking open of theological reserves that will transgress, startle, renew, instruct. This is sacrifice, re-made."e; Professor Katherine Sonderegger, Virginia Theological Seminary

Prologue: The Broken Body

This book is concerned with how and where Christians encounter Jesus Christ and acknowledge his identity, in all its mystery and fulness. It also asks, secondly, how believers can, or should, then best express what they believe about him. And finally, and thirdly, it begins to probe how that expression is bound up with what they necessarily do to live out that belief and embrace its demands, not only through Christian sacramental and ecclesial practices, but also on the borderlands of the church, and especially in the historic and fraught relationship of Christianity to Judaism. For it is thus, I propose, that they come to ‘know’ Christ ‘more nearly’, both through habituation and continual surprise.

These three tasks constitute, as I see it, the fundamental concerns of any attempt at a ‘Christology’ – that is, any adequate expression of the contours of belief in Christ as the salvific God/Man. But beyond and beneath these initial concerns, and perhaps more challengingly, this book asks in various ways what initial human presumptions or attitudes have to be broken in order for any proper response to emerge to these core riddles of Christian faith in relating to Jesus Christ. That issue is my central concern in what follows immediately in this Prologue. The lines of thought about such ‘brokenness’ may, perforce, not be immediately familiar ones, and certainly they are ones which in some cases could court controversy and critique; and hence the need to explain them anticipatorily. But as I shall argue here, they are vital for any rich and discerning understanding of the christological task.

I should also immediately make it clear at the outset, moreover, that this is therefore a book of essays that should be read as prolegomena to any future Christology, rather than as a full and substantial Christology per se.1 That is, I am engaged in this book in preliminary explorations,2 which will shape what I finally wish to say about Christ as the fulsome revelatory divine presence in any ‘systematic’ theology worthy of the name. But these preliminary explorations are necessary steps, because none of them is completely obvious in the current theological terrain, and several of them may even seem surprising or contentious. Let me now explain.

The Christological Question

‘Who is Christ?’ This is a deceptively simple question, and it hides a multitude of possible theoretic ‘sins’ and differences of opinion only scarcely below the surface of immediate theological consciousness. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of the most perspicacious commentators on this topic in the modern period, left only lecture notes on the problem (‘the christological question’, as he himself called it);3 but he was one of the few theologians in the twentieth century to have pinpointed with such insight its real richness and its accompanying difficulties. It is not for nothing that his analysis starts with the insistence that ‘silence’ should precede any attempt to answer this question – since Christ, he says, is essentially inexpressible, whilst at the same time supremely revelatory: thus, ‘The silence of the Church is silence before the Word’.4 A true Lutheran, however, Bonhoeffer goes on immediately to fulminate – contentiously, of course – against the suggestion that this silence might be the silence of what he calls the ‘mystics’; for he takes it that their ‘dumbness’ would be both solitary and self‐referential. Instead, he says, an essential paradox has to be grasped at the outset of the christological task: ‘To speak of Christ means to keep silent; to keep silent about Christ means to speak. When the Church speaks rightly out of a proper silence, then Christ is proclaimed’.5

Ironically, however, the ‘mystic’ in the Western tradition who most closely anticipated this paradoxical insight of the Lutheran Bonhoeffer about a ‘proper silence’ before Christ was the sixteenth century Carmelite friar, John of the Cross, only a slightly later contemporary of Luther himself. As John wrote in one of his most famous aphorisms: ‘The Father spoke one Word, which was his Son, and this Word he speaks always in eternal silence, and in silence it must be heard by the soul’.6

The essays that follow in this book cannot therefore be said to be straightforwardly ‘Bonhoefferian’, for – amongst other differences from him – they engage insistently with earlier traditions of ‘mystical theology’ (patristic and medieval) towards which Bonhoeffer harboured a certain suspicion, and which find a certain climax in John of the Cross himself. But what they do share with Bonhoeffer is an intense interest in analyzing what can, and cannot, be said in the task of Christology (out of a ‘proper silence’), and what therefore remains the necessary arena of divine revelatory mystery, indeed the unfinished business – at least from our human perspective – in any authentically Spirit‐filled response to the crucified and resurrected Jesus. And what goes along with this insight is an attempt to clarify first and afresh, as Bonhoeffer also did so presciently and in his own way, what must thereby be the relationship between certain primary elements in any modern christological armoury: the ‘Christ’ as biblically proclaimed in the New Testament; the ‘historical Jesus’ as earnestly probed behind the biblical texts by modern critical scholarship; and the patristic tradition of metaphysical speculation as to Christ’s ‘person’ and ‘natures’.

Understanding how these three different genres of reflection on Christ relate, or should relate, in our quest for Christ’s ‘identity’ is one of the most complex and subtle questions of contemporary Christology: it is, after all, a special conundrum created by the modern period in its forging of a newly intense appeal to the second element in this triad.7 I choose to tackle this issue head‐on in the opening chapter of this book. Immediately, and out of this initial reflection, an argument of my own starts to emerge about how any proper response to the identity and presence of the risen Christ is necessarily ‘apophatic’ in a particular sense, that is, ‘broken open’ to the unexpected and the mysterious in the Spirit’s brokerage of a form of displacement from our natural expectations and categories.8 We would – reasonably enough, or so it seems – like to catch and hold what we might know and recognize in Christ, to make it our own possession, even express it in purely propositional terms; and the modern ‘quest’ for Jesus as an object of critical historical investigation inevitably courted, from the start, this ambition to probe to a new level of certainty about what could be verified about his life, teaching and person, as if the mystery that inevitably surrounds God in Godself could somehow be dispelled or moderated in the case of his Son. For often we still presume that getting at the ‘historical’, or ‘human’, Jesus will be the proper means of taking hold of what we need to know in responding to a more elusive divine revelation.9

Worse: the ambition may even be extended to a felt need to justify, by historical and empirical means, the very metaphysical claims enshrined in later credal statements about the second Person of the Trinity. But this, I submit, is a vain and misplaced propulsion – a ‘category mistake’ – as is argued at some length in Chapter 1. Attempting to map the modern ‘historical Jesus’ directly onto the historic creeds in this way is fraught with confusion,10 not least because it also sometimes attempts to short‐circuit, and even displace, the issue of what it is to encounter the risen Jesus – without which the question of the ‘identity’ of Christ is idolatrously shrunk from the outset, and the historic creeds denuded of all their soteriological power.

It follows, as I go on to argue further in Chapter 1, that although the modern ‘historian’s Jesus’ inevitably and rightly retains enormous and enticing interest for all Christians who seek to deepen their understanding of the identity of Christ in his historical manifestation (even though this quest remains fraught with endless scholarly disagreements of interpretation), it cannot be either the justificatory starting point, nor the constraining and final criterion, for his divine reality: this is one of the most significant areas in which an apophatic ‘saying no’ has to occur in Christology. Yet, in a slightly different sense of ‘saying no’, this ‘historian’s Jesus’ can indeed have a crucial role, as I also argue in Chapter 1, in being deployed strategically against ideological, distorted or idolatrous renditions of that same Jesus. In other words, we must say ‘no’ to attempts to defuse or ignore his risen mystery, just as we also say ‘no’ to attempts to hijack his risen reality for falsely political, distorting, or even merely complacent ecclesiastical ends.

It is thus not coincidental that Bonhoeffer was the modern theologian so particularly concerned to locate the (to him, judiciously...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-78080-9 / 1118780809 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-78080-0 / 9781118780800 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,5 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich