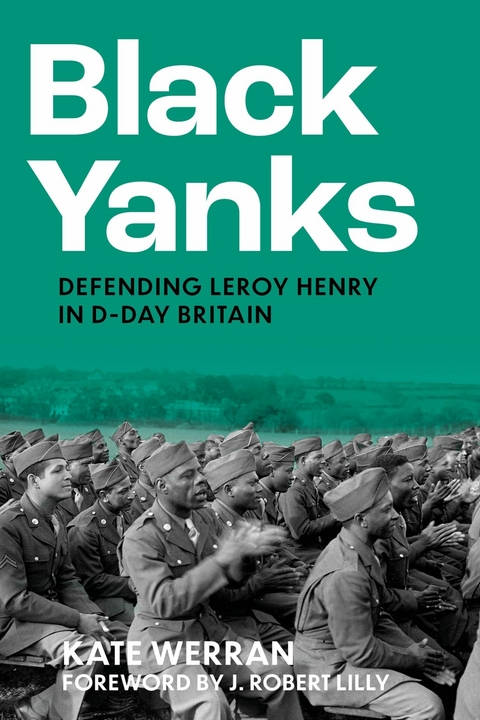

Black Yanks (eBook)

288 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-353-9 (ISBN)

KATE WERRAN is a specialist on the US army that was stationed in Britain before, during and after D-Day. Her first, award-winning book An American Uprising in Second World War England was optioned for documentary and scripted drama. Kate came to writing after a career in journalism, and she has produced critically acclaimed twentieth-century history programmes for the BBC, Channel 4 and Channel 5. In 2024, she was elected to the Royal Historical Society as an Associate Fellow.

Black Yanks is the story of how an African American soldier from Missouri ended up on death row in D-Day Britain - and the extraordinary campaign that set him free. The drama plays out over a tumultuous six weeks, set against a backdrop of the most audacious sea-borne invasion ever attempted. As the build-up to D-Day escalates, Leroy Henry's story unfolds, allowing us to view a pivotal point in history with an entirely new perspective: making race, the 'special relationship' and the British peoples' collective powerful key considerations. This fascinating, alternative timeline reveals an edgier wartime society, hidden tensions in Anglo-American relations and the moment the British tabloid press learned to roar. Ultimately, Leroy Henry's court martial and everything it stood for provoked mind-blowing decision-making at the highest military level. Kate Werran unearths a wealth of archival material to help disclose the story behind the first significant, if uncelebrated, win in the civil rights movement; a story that has been overlooked for nearly eight decades. Until now.

Prologue: 26 May 1944

Twenty American soldiers trooped into a small room on a British prison wing just before 1 a.m. on 26 May 1944. They had been forewarned by their commandant that things would get grisly and to leave if they felt ‘the least bit faint’. At five minutes before the hour, Private Wiley Harris Jr, an African American soldier, was led in via a door concealed behind a bookcase in his adjoining cell. The serviceman from Greenville, Georgia, was now face to face with the gallows that awaited him. His last few steps brought him to a standstill over the scaffold’s trapdoor; known as ‘the drop’.

This was Shepton Mallet in Somerset, one of Britain’s oldest prisons and since 1942 a US Army jail complete with an execution chamber its American occupiers had revamped. Thick, stone perimeter walls some 75ft high shielded the newly dubbed 2912th Disciplinary Training Center from the outside world.

The only British aspects to the killing process (other than its location) were the style of hanging and the executioners: septuagenarian Thomas Pierrepoint and sometimes his nephew Albert, who later recalled:

They were allowed most of the American customs except the actual method of execution; no standard drop, no hangman’s knot, but a variable drop on a modern noose suspended from a British gallows and designed [to ensure] instantaneous death.1

Having followed his father and uncle into the family business of state execution, Albert Pierrepoint was no stranger to the macabre, but he drew the line at some of the more bizarre rituals of American judicial killing in the Second World War. The peculiar middle-of-the-night timing of executions was one. ‘Another custom which was strange to me was the practice of laying on a mighty feast before the execution,’ he continued. ‘We were eating badly in this country at that time, but at an American execution you could be sure of the best running buffet and unlimited canned beer.’2

Private Harris Jr was about to suffer a third idiosyncrasy – the American habit of making death row prisoners spend long, fateful minutes pinioned in position, poised for death. Every vestige of military insignia had already been ritualistically stripped from the condemned man’s uniform as a public demonstration of his shameful army dismissal.

Commandant Major James C. Cullens now stepped up to read the charges and explain why the prisoner was going to be executed. To the men tasked with hanging Harris Jr, this detail, the ‘sickening interval between [our] … introduction to the prisoner and his death’ was the ‘hardest’ custom of all to stomach.3

Assembled army witnesses heard that Private Wiley Harris Jr had been court-martialled for murder, found guilty and sentenced to death. One wonders what the 26-year-old soldier was contemplating at this point. His last moment of freedom had been a twenty-four-hour pass from the 626th Ordnance Ammunition Company’s camp in County Down, Northern Ireland.

Private Harris Jr had been drinking with friends at the Diamond Bar in Belfast on 6 March 1944 when he bumped into the shady Harry Coogan, who promised to arrange an assignation with young Eileen Megaw. The American was tricked into handing over £1 for the promise of sex. Having paid up front by torchlight, he was starting to undress in the unused air-raid shelter that had been commandeered for the purpose when Coogan called a warning from outside. Police were coming and they needed to run.

Going outside and seeing there were none, Private Harris Jr asked Megaw to return to the shelter. When she refused, he realised he’d been deceived and demanded his money back. Coogan told her not to, but Megaw dropped the coins accidentally while running away up the street. It was while the GI stooped to pick them up that Coogan struck him on the cheek, shouting: ‘This n****r is going to stab this woman and I am not going to let him.’4 Which was when Harris Jr pulled out a knife and stabbed Coogan sixteen times. Murder charges were brought within days.

Racism was key to the ill-fated hustle. It framed the pimp’s insult, triggered a lethal response and clouded subsequent legal proceedings. Private Harris Jr must have realised there could be no good outcome when the prosecutor wanted to know whether ‘any member of the Court has scruples which would prevent him voting for a sentence of death’.5 Neither did claims that investigators tricked him into making a statement carry any weight with the army panel at Victoria Barracks in Belfast.6

Nor could the verdict of a British inquest, four days later (which found ‘no premeditation or malice aforethought’), sway the US Army’s still unannounced decision. The British jury independently decided it was manslaughter not murder. Belfast Coroner Dr H.P. Lowe blamed Coogan for his own death, describing his conduct as ‘a disgrace to all right-thinking men’ and Megaw’s as symbolic of a ‘great lack of parental control over young girls in the city’.7 Dr Lowe concluded that Harris Jr’s actions were frenzied rather than premeditated – the crucial and differentiating component of murder.

It should have made the difference between life and death to Private Harris Jr, especially given this was the British coroner’s findings about the demise of one of its own. But the US military court found Private Wiley Harris Jr guilty of murder anyway. Two months later, the death sentence was confirmed, and it was announced that the punishment would be carried out within forty-eight hours.

Perhaps as Private Harris Jr stood listening to the commandant, he might have considered Northern Ireland’s vehement and vociferous opposition to his plight. Pleas for clemency quickly poured in as soon as the verdict was made public; partly in response to particulars of the killing, but also because it tapped into British fears that the US Army punished its Black soldiers too harshly.

People wrote letters begging for Private Harris Jr to face prison time rather than death, and right up until the last minute they kept coming. Incensed citizens prompted the city’s council, the Belfast Corporation, to initiate a flurry of urgent telegrams. The lord mayor sent one pleading for Harris Jr’s life as did political organisations including the Labour Party and Communist Party. The Belfast Trades Council sent strongly worded messages to Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Sir Basil Brooke in addition to all five major workers’ unions, ranging from the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers’ Union to the Municipal and General Workers’ Union. Roman Catholics and Protestants overcame their differences to agitate for Private Wiley Harris Jr. That this ‘astonishing unanimity’ happened ‘in a city noted for its religious divisions’ made it even more monumental.8

This growing crescendo of ‘dramatic eleventh-hour efforts’ prompted Leader of the House of Lords Viscount Cranborne to write urgently to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt that ‘ninety-nine per cent of people in Britain opposed the execution of Wiley Harris and … it would damage Anglo-American relations should he be hanged’.9

Knowing this might have been a comfort to Private Harris Jr as the commandant read on. Kinder still, believed executioner Albert Pierrepoint, would be to get the sentence over and done with. ‘Even a few seconds can be a long time when a man is waiting to die,’ he reflected later. ‘Under British custom I was working to the sort of timing when the drop fell between eight and twenty seconds after I had entered the condemned cell,’ he continued.10 Famously, he boasted of lighting a cigar before entering the execution chamber and being able to pick it up still smouldering after expertly dispensing with British civilians in record time.

Private Harris had been standing on the ‘drop’ for more than three minutes in a crowded room measuring roughly 4.3m × 3.6m – the size of a very small modern British garage.11 But his wait was still not over because now, according to his death record:

The commandant … addressed the prisoner as follows … ‘Wiley Harris do you have a statement to make before the order directing your execution is carried out?’

Private Harris: ‘I don’t have any statement to make sir.’

Chaplain John Ridout addressed the prisoner as follows. ‘Do you have anything you want to say to me?’

Private Harris: ‘I appreciate what you did for me sir. I appreciate what everybody did and I want to wish everybody good luck.’

Eventually, the official record shows that following ‘silent signals given by the commandant, the executioners proceeded’.12

Normally, the ‘silent signal’ was the last word of the chaplain’s prayer, invariably ‘Amen’. During the first US military execution in Britain the previous year, great care and attention had been taken to note every utterance of the proceedings right down to the wording of the final psalm. Twelve months and several deaths later, attention to detail had faded. Private Wiley Harris Jr was the sixth American soldier to be hanged at Shepton Mallet. As the procedure became more routine – and the execution unit more inured to its niceties – even the fact that prayers were uttered was no longer documented.

It took four minutes from Private Harris Jr entering the execution chamber...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | J. Robert Lilly |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | African American • african american solider • american soldiers in britain • Anglo-American Relations • Bath • black soldier • Capital punishment • Civil Rights • court martial • d-day britain • Death Row • death sentence • leroy henry • Missouri • Second World War • Special Relationship • wartime society • World War 2 • World War II • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-353-7 / 1803993537 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-353-9 / 9781803993539 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich