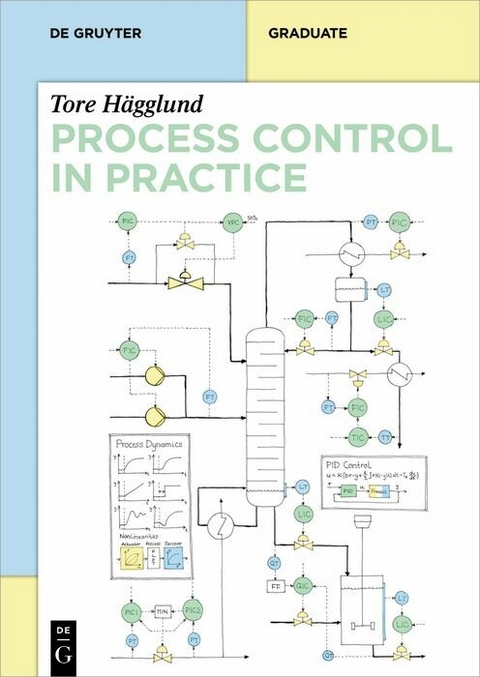

Process Control in Practice (eBook)

207 Seiten

De Gruyter (Verlag)

978-3-11-110746-2 (ISBN)

This book covers the most important topics that people working as process control engineers and plant operators will encounter. It focuses on PID control, explains when to use P-, PI-, PD- or PID control as well as PID tuning and includes difficult to control process nonlinearities such as valve stiction or sensor problems. The book also explains advanced control strategies that are necessary when single loop control gives insufficient results.

The key features of the text in front of you are:

- This book is a result of teaching the material to industrial practitioners over three decades and four previous editions in Swedish, each of which was a refi nement of the previous one.

- A key contribution of this book is the careful selection of what is required when you are at a plant and have to make sense of what you see.

- The book is written in such a way that it does not assume mathematical knowledge above the compulsory school level. Process control sits between control engineering and process or chemical engineering and often there is a distinct gap between the two. By explaining both the fundamentals of control and the processes the book is written to appeal to control engineers and process engineers alike.

- The book includes exercises and solutions and thus lends itself for teaching in the classroom.

Tore Hägglund received his M.Sc degree in Engineering Physics in 1978 and his Ph.D degree in Automatic Control in 1984, both from Lund Institute of Technology, Lund, Sweden, where he currently is professor. Between 1985 and 1989 he worked for Alfa Laval Automation (now ABB) with development and implementation of industrial adaptive controllers.

Tore Hägglund has written several books, e.g. PID Controllers: Theory, Design, and Tuning (coauthor K. J. Åström), and Process Control in Practice. His current research interests are in the areas of process control, tuning and adaptation, and supervision and detection, with applications mainly in the pulp and paper industry.

1 Introduction

The title of this book is Process Control in Practice. Most of the content is not limited to the process industry, but is useful in other industries where control technology is also used. However, most references will be made to the problems and needs of the process industry.

1.1 Industrial Process Automation

Most process industries have developed over a long period of time, in several cases for more than a century. Initially, these industries were run largely manually, which meant that people were out in the facilities and ensured that temperatures, pressures, flows, levels and other process variables were maintained within reasonable limits by manually adjusting valves, pumps and other control devices. Gradually, these industries became more automated, which meant that people were replaced by automation equipment and controllers. Staff nowadays rarely work inside the production facilities, but monitor the process from a control room. The number of employees in the process industry has also declined sharply in recent decades. This means that fewer and fewer people are monitoring larger and larger process sections. At the same time, the processes have become increasingly more sophisticated which has resulted in higher production yield and higher quality of the products.

The relatively slow and gradual increase of automation in the process industry has resulted in decentralised control strategies. In paper mills, for example, there are thousands of controllers that maintain process variables at desired values. These simple control loops are in turn interconnected in an ingenious network ensuring that the overall goal of the production is achieved. This network has been developed over a long time by many people and is based on in-depth knowledge of process operations and process characteristics.

A prerequisite for the development of the process automation industry is that the equipment used in automation has developed further. In the nineteen sixties, people first started using computers in the process industry. Prior to that, all controls were handled with analogue technology, usually with pneumatic devices. Towards the end of the nineteen seventies, computer-based controllers and control systems had a serious break-through in the process industry. The introduction of computers meant completely new possibilities for control technology solutions and monitoring of the processes.

It is interesting to note that despite the advent of computers in the process industries the processes today are largely controlled with the same control strategies that were employed before computers arrived. This has surprised many, but the reason is that the solutions developed by generations of people who lived close by the processes are based on so much knowledge that they are difficult to surpass. Of course, there are cases where, for example, new optimisation methods have provided improved performance, but these usually work at a higher level where they determine setpoints for the existing underlying base level control described here. In this book we review the comparatively simple methods of base level control.

1.2 Single Control Loop

In the decentralised control strategies used in the process industry the single control loop is the basic and most important building block. A modern industrial process can comprise hundreds or thousands of individual control loops that all work together to manage the production.

Figure 1.1 shows a block diagram describing an individual control loop. The loop consists of two parts: the process and the controller. The process re presents a process section, the output of which you want to control. This output can be the level in a tank, the flow or the pressure in a line, the temperature in an oven or the concentration in a flow.

The process connects the controller output to the process variable. In the figure, these are denoted by u and y, respectively. These designations have become standard in the control literature, but in product manuals you often see other designations. The process variable y (PV), sometimes also called measurement value, is the quantity we want to control and is in most cases the signal from a sensor. In order to be able to control the process variable, we must be able to influence the process. We do this by varying the controller output u, which often is the signal to a valve or a pump. The controller output (OP) is also sometimes referred to as the control variable or control signal.

The objective of the controller is that the process variable y should follow a set-point. The setpoint (SP) is also called reference signal and is denoted by r in the figure. In some control applications, you want the process variable to follow a frequently changing setpoint. In process control, the setpoint usually does not to change often. Rather, outside disturbances make it difficult to keep the measurement value close to the setpoint.

The control loop in Figure 1.1 shows how to solve the control problem using feedback. In feedback control, the measurement signal y is compared to the setpoint r. The comparison determines the value of the controller output u. The comparison and determination of the controller output is performed by the controller. The controller is the second important component in a control loop.

Fig. 1.1: A single control loop.

1.3 Organisation of this Book

The book first studies the single control loop, that is, the feedback loop of a process and a controller. This is done by reviewing various ways to describe the properties of the process, the structure of the controller and its tuning. Thereafter follows a discussion of the largest source of problems in control loops, namely, nonlinearities. The last chapter moves beyond single loop control by investigating what happens if several loops work together in one implementation. In other words, we start with a single control loop and work towards larger implementations and control strategies.

Process understanding is a prerequisite for successfully controlling the process. Chapter 2 describes different methods for investigating and describing the dynamic properties of processes. The most common way to determine the dynamic properties of processes in the process industry is to use step response experiments. The chapter describes different ways of analysing and describing the dynamics of processes with the help of such experiments. These descriptions form the basis of several of the methods to tune the controllers as described later in the book. This chapter also includes a classification of different types of processes that are commonly found in the process industries.

The PID-controller is by far the most common controller in the process industry. Chapter 3 describes the PID-controller in detail. First, the structure of the PID-controller is explained. Incidentally, the different parts of the PID-controller are a natural extension of the most basic type of controller—the on/off controller. The description of the structure of the PID-controller also provides natural explanations of how the controller’s parameters affect the control performance. Different suppliers have chosen to implement the PID-controller in different ways. These variants are also discussed in this chapter.

Chapter 4 deals with different ways of tuning PID-controllers, both simple manual methods and methods based on the step response experiments described in Chapter 2. Methods based on examining the dynamics of the process by tuning the control loop so that it starts oscillating are also discussed. The chapter concludes with a description of the principles of automatic controller tuning.

Chapter 5 focuses on different types of nonlinearities that occur in control loops and describes how to deal with them. Nonlinearities often occur in valves in the form of backlash and friction. Even well maintained valves often have a nonlinear characteristic. Nonlinearities also often occur in sensors, and the process itself can be non-linear. Gain scheduling is a systematic and relatively simple way to deal with many types of nonlinearities and is detailed in this chapter. The chapter concludes with a description of adaptive methods that can also be used to handle nonlinear processes.

Chapter 6 describes the most common control strategies used to connect single control loops. When instrumenting the controller, information is sent between different functions via signals. These signals may often need to be filtered so that they do not contain too much noise and other incorrect information. Different types of filters are described in Section 6.2. Selectors are logical components that are used to switch between different control strategies. This is described in Section 6.3. Cascade control, as described in Section 6.4, is a way of connecting two controllers and thereby having a controller structure that corresponds to a more advanced controller than the PID-controller. Feedforward is another way to improve the performance of the PID-controller. It is based on the principle that you should compensate for measurable...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.8.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | De Gruyter Textbook | De Gruyter Textbook |

| Übersetzer | Margret Bauer |

| Zusatzinfo | 79 b/w and 65 col. ill., 11 b/w and 0 col. tbl. |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Technik |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Advanced control strategies • Implementation and practical modifications • PID Control • PID Tuning • Valve stiction and backlash |

| ISBN-10 | 3-11-110746-9 / 3111107469 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-11-110746-2 / 9783111107462 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich