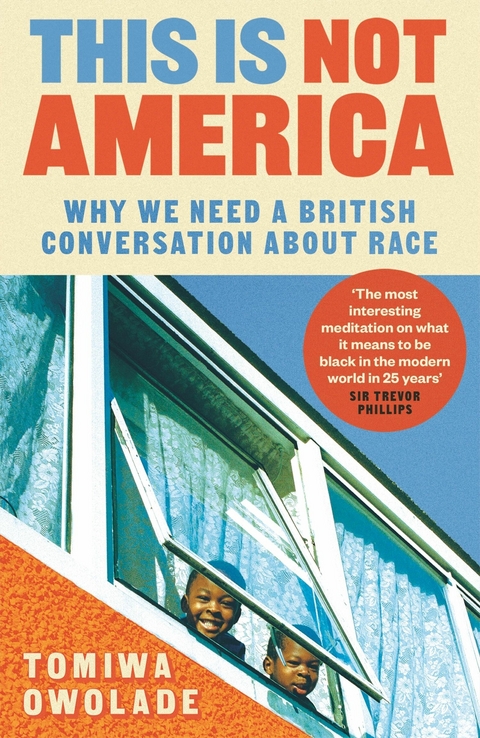

This is Not America (eBook)

336 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-622-6 (ISBN)

Tomiwa Owolade writesabout social, cultural and literary issues for the New Statesman,The Times, the Sunday Times, the Observer, UnHerd and the Evening Standard. He has appeared on BBC Radio 4 and Times Radio discussing some of the ideas in this book. He won top prize at the RSL Giles St Aubyn Awards 2021.

Tomiwa Owolade writesabout social, cultural and literary issues for the New Statesman,The Times, the Sunday Times, the Observer, UnHerd and the Evening Standard. He has appeared on BBC Radio 4 and Times Radio discussing some of the ideas in this book. He won top prize at the RSL Giles St Aubyn Awards 2021.

1

DOUBLE CONSCIOUSNESS

Black and British: two equally important identities. But we can understand why racial solidarity exists, is seductive even, and why many black people emphasize their racial identity over and above other forms of attachment that might define them – such as their attachment to a place. They do this as a shield against racism. Racial solidarity is a form of belonging, when other forms of belonging are denied to you – such as your sense of belonging to a nation. If you are denied the same rights as your fellow citizens on the basis of your race, or you are treated as a foreigner in any other way, then it makes sense to opt for an identity that crosses national boundaries. And to attach yourself to people who share your racial identity and are marginalized in their own country. Blackness thus becomes a substitute for Britishness.

Black and British can thus seem as if they are in tension, because black people have sometimes been made to feel like they do not belong in Britain, and so have leaned into their racial identity as an alternative source of belonging. But the most convincing case against racism is not to fall into the trap of embracing your racial identity above all else. It is to show that there is more to you than your racial identity. There is your religion, your family, your home city, your individual experiences. There is also your nation. Racists think someone’s race is the only important thing about them. Anti-racists should reject this. Focusing only on their race undermines somebody’s humanity; it denies the variety of their lived experiences. You can’t humanely approach black British people by focusing only on their blackness.

The same is true of black Americans. The American matters just as much as the black. The United States, though, has historically denied the political, legal and social rights of its black population. Black people in America have often been made to feel more black than American. Against this racist imposition is the fact of their American identity. W. E. B. Du Bois hypothesized this tension – between black and American – and gave a name to it: double consciousness. This chapter looks at the concept of double consciousness, and argues that it comes from an American context. The struggle to reconcile blackness and Americanness, and the argument that those things are in fierce tension, are coming from an American frame of reference.

In the first chapter of his acclaimed essay collection, The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois writes: ‘One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.’1 Understanding the ‘two souls’ of black Americans is crucial to understanding their identity. For Du Bois, these souls are in conflict with each other. They are unreconciled. And it is easy to see why he believed this: he lived between 1868 and 1963. He was born five years after the Emancipation Proclamation Act that abolished slavery in America, and he died the year before the Civil Rights Act that abolished segregation.

Du Bois was one of the greatest American intellectuals of the twentieth century. He was also, in the words of his biographer David Levering Lewis, ‘the premier architect of the civil rights movement in the United States’.2 His death was announced on the day of one of the most important events in the American Civil Rights Movement: the 1963 March on Washington. Just before Martin Luther King gave his iconic ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, Roy Wilkins, then head of the NAACP, stepped up to the podium to announce that Du Bois, who was one of the founders of the NAACP, had died. The culmination of the long struggle for civil rights came the day its intellectual lodestar died in a foreign country – in Ghana, 3,000 miles away.

After Du Bois’s death, condolences came from all over the world: Nikita Khrushchev of Russia, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria, Walter Ulbricht of East Germany, Kim Il-Sung of North Korea. Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai also expressed sadness at his passing – Du Bois’s birthday soon became a national holiday in communist China. No one from the American embassy in Ghana was there at his funeral. By this time, Du Bois had renounced his American citizenship and had embraced an ideology and movement that spanned the world: communism. He had formally joined the Communist Party three years previously, in October 1960, when almost everyone else had left because of the ruthless crushing of the 1956 Hungarian revolution. Du Bois was a proud anachronism: by the time he died, at the age of ninety-five, he was more radical than when he was twenty-five. He was eventually buried in Osu Castle in Ghana, where European slave traders had captured many Africans and taken them from there to the New World. He had, in one sense, come home. But Du Bois was an American – not an African. And despite his later affinity with an internationalist ideology, much of his earlier and most influential work was dedicated to questions of nationhood and race. What it meant to be a black American.

Du Bois was also an uncommon type of black American. He was born and brought up in New England, in the town of Great Barrington, at a time when most black people in America came from the Deep South. He had French Huguenot ancestry, but insisted that his name should be pronounced in the Anglo-Saxon style as ‘Due-Boyss’ rather than the Gallic ‘Doo-Bwah’. After studying at Great Barrington High School, he took a bachelor’s degree at Fisk University, the historically black college in Tennessee. This was his first taste of the American South. But fourteen out of the fifteen faculty members of Fisk were white, abolitionist, northern and overwhelmingly Congregationalist; the very same people Du Bois was accustomed to from his childhood. It was a liberal arts college. Students were taught Greek, Latin, French, German, theology, history, natural sciences and moral philosophy. The purpose of the university was to create an African-American version of the New England elite. Du Bois later took another bachelor’s degree and obtained a PhD at Harvard: in doing so, he became the first black American to be awarded a doctorate at Harvard University.

He was a black man who funnelled himself through the institutions reserved for a white American elite. For Du Bois, ‘the history of the American Negro is the history of this strife’: the strife between the Negro and the white American. He said that the American Negro ‘would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa’, and ‘he would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American.’3 He sought to explain why the hard division between Negro and American was false. He himself was living proof of that.

***

I have never really suffered from double consciousness. Much of my frustration with contemporary anti-racism is the conviction that I am more than being black. But I am often seen for my race and little else. Because black people have historically been victimized by white people, this means I am seen as a victim in need of rescue. I chafe against this. This is not an intellectual response from me; I feel at a gut level this kind of ‘activism’ or ‘allyship’ is patronizing. But there is also a robust logical case against it. If you don’t treat black people with the same moral standard as white people, you exclude them from the circle of humanity. I have felt this strongly for a very long time – before I started to look seriously into the subject of race. It was not always the arguments that were made in defence of this worldview that triggered a negative response from me. It was the tone. A mixture of pity and sanctimony. Two incidents from my late teens illustrate my frustrations.

The first dates from when I was applying for university. One of my teachers, a sweet and eccentric Scottish woman called Ms Stuart (not her real name), suggested I apply to SOAS, a university apparently famed for its generosity towards black and ethnic-minority students. Her intentions were noble. She wanted to give me a helping hand in terms of my university opportunities. Maybe I should have been grateful. But my immediate response to her suggestion was a visceral mixture of offence and embarrassment. This was offensive to both SOAS and me. The university is more than a charity for black kids, and I was more than the sum of my race. I smiled at her and acknowledged her advice. But later that evening I removed SOAS from the list of the universities I would apply to. It was tainted indelibly by her condescension.

I had a feeling that Ms Stuart’s primary motive was to show me that she was a good person. It wasn’t a matter of sincerity; I’m sure she genuinely believed she was doing good. And I still think of her as a good person and have no ill-feeling towards her. Her suggestion was aimed at improving my life. The problem I had with it was the idea that my whole person could be reduced to my race. Her display of benevolence came at the expense of my humanity. I didn’t just want to be the black guy in university. I knew I was much more than that.

I was sensitive to being patronized by my teacher or by any other white person in authority...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.6.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Makrosoziologie | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | afropean • Akala • America • BAME • Ben Judah • Black and British • black britain • black british life • Black History • Britain • critical race theory • Cultural Criticism • David Olusoga • Diane Abbott • Diversity • Empire • ian buruma • Immigration • imperialism • Intersectionality • Mixed Race • Politics • Race • racial injustice • Racism • renni eddo lodge • Tom Holland • tomiwa owolade • Windrush |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-622-0 / 1838956220 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-622-6 / 9781838956226 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich