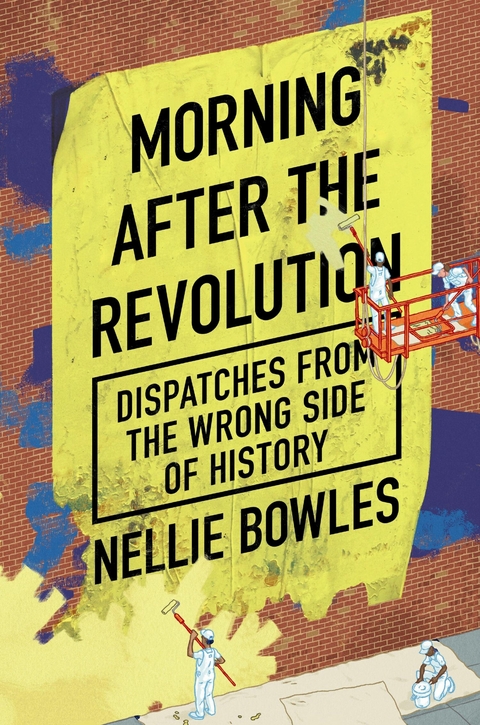

Morning After the Revolution (eBook)

304 Seiten

Swift Press (Verlag)

978-1-80075-272-6 (ISBN)

Nellie Bowles is a writer living in Los Angeles. Previously, she was a correspondent at the New York Times where, as part of a team, she won the Geral Loeb Award in the investigative category and the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Journalism Award. Now she is working with her wife to build The Free Press, a new media company.

'Not since Joan Didion in her prime has a writer reported from inside inside a system gone mad with this much style, intelligence and wit ... A perfect book' Caitlin FlanaganFrom former New York Times reporter Nellie Bowles comes an irreverent romp through the sacred spaces of the new left. ?As a Hillary voter, a New York Times reporter, and a frequent attendee at her local gay bars, Nellie Bowles fit right in with her San Francisco neighbors and friends - until she started questioning whether the progressive movement she knew and loved was actually helping people. When her colleagues suggested that asking these questions meant she was 'on the wrong side of history,' Bowles did what any reporter worth her salt would do: she started investigating for herself. The answers she found were stranger - and funnier - than she'd expected. In Morning After the Revolution, Bowles gives readers a front-row seat to the absurd drama of a political movement gone mad. With irreverent accounts of attending a multi-day course on 'The Toxic Trends of Whiteness,' following the social justice activists who run 'Abolitionist Entertainment, LLC,' and trying to please the New York Times's 'disinformation czar,' she deftly exposes the more comic excesses of a movement that went from a sideshow to the very centre of Western life. Deliciously funny and painfully insightful, Morning After the Revolution is a moment of collective psychosis preserved in amber.

A Utopia, If You

Can Keep It

It’s a little offensive now to say that the occupation of this Seattle neighborhood by a group of anti-fascists was a party, because bad things did happen (a boy was killed), but for a little while, inside the new armed borders of the hippest neighborhood in town, it really was a party.

The neighborhood arose in the summer of 2020, during the surreal months when Covid coincided with the renewed Black Lives Matter movement, which sought to reshape how America polices. White-collar workers were home, Zooming for a meeting or two, freaked out, angry, online, alone, and generally very available, all the time. And America’s police were caught on camera doing what sure looked like a murder (a knee held on the neck of a black man). Things felt open-ended and chaotic. When a group of black-clad anti-fascists in ski masks marched into Seattle’s historically gay neighborhood of Capitol Hill to start a new police-free autonomous zone, there was a collective shrug. Why not? How about we see?

There’d been protests for a week in the neighborhood before the new borders went up. Police had put barricades around the precinct when the protests heated up, around June 1. Half a dozen elected officials joined in with the anti-fascists and Black Lives Matter crowds to protest. Nights were especially raucous. The crowds grew. Police boarded the precinct windows. They put in stronger barricades. Finally, during the middle of the afternoon of June 8, the police abandoned the precinct. It was a huge win for the protestors. Right away they dragged the police barricades out, using them to build new neighborhood borders. (Eventually Seattle’s Department of Transportation would come in to help install nice concrete barriers.) The new city was formed. It was five and a half square blocks.

Along the edges of the community, young men sat on lawn chairs with long guns on their laps. They didn’t stop much of anyone, except troublemakers. Reporters, they would sometimes stop. The autonomous zone was not a free-for-all. The young men were mostly locals, public school teachers, baristas, grad students, and various healing arts practitioners. They were masseuses and Reiki specialists. They were vaguely underemployed software engineers working on Zoom. It was less zip-tiecarrying Navy SEALs, like you might find on January 6, and more young people who were described as sensitive or stoned. Which is not to say they were uncomfortable with violence. Putting violence back on the table—being armed, being even a little scary—was the core of Antifa’s method.

Within the walls of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, the new residents could make a utopia. It would be called CHAZ. It would be a place without the old world’s racism and the old ways of talking and thinking. This would be an entirely different project: A fresh start. Anyone who crossed into the new city would be automatically on board. Those who happened to be there already would have to get on board or leave. No one wants to live in capitalist hell—CHAZ was a gift.

The founders of the new neighborhood, set atop the old one, dug into the park lawn and planted a community garden, and the good Seattle mist helped it grow. They set up a free neighborhood library, giving books to all. They set up a clinic providing health care, for everyone, and while the care was basic, it was also free. Food trucks came and musicians did too. Cops couldn’t enter CHAZ and didn’t need to, thanks to community-run safety efforts and a new culture of equality and compassion that would make crime all but disappear. Weeknights were a smorgasbord of activities—movie nights and dodgeball games, Marxism readalouds. The city’s homeless and addicted were welcomed with open arms. Art could and did go everywhere—on the pavement, the asphalt, the walls of shops and restaurants.

If you didn’t know what happened at night and if you didn’t look too closely at the armed guards on the edges of the new city, if you didn’t see that the community library was just some books on a folding table, and if you didn’t think about what exactly was the sewage and waste disposal plan here, if you stopped being so suspicious and just enjoyed something for once, then you’d have seen the perfection in CHAZ. For a generation more comfortable tapping on the glass of their phones, here in the newly liberated CHAZ was something tangible.

The neighborhood had been one of those nice, liberal, gentrified ones, with rainbows painted onto the crosswalks. The insurgents who laid claim to those blocks said that progress didn’t need to be incremental. It could happen fast. A revolution didn’t need to be polite.

Seattle’s then mayor, Jenny Durkan, loved it. She was in her early sixties, typically dressed in bright blazers and white pearls, her strawberry blonde hair perfectly blown out into the helmet that’s popular for successful women of that age. The autonomous zone had “a block-party atmosphere,” she told curious reporters. President Trump took aim at her and the city, describing Seattle as having been taken over by domestic terrorists. He wrote: “Take back your city NOW. If you don’t do it, I will. This is not a game. These ugly Anarchists must be stopped IMMEDIATELY. MOVE FAST!” She said instead that it was “a peaceful expression of our community’s collective grief and their desire to build a better world.” She especially loved the “food trucks, spaghetti potlucks, teach-ins, and movies.” She sent barbed wire and Porta-Potties to the autonomous zone.

Politically, lots of anti-fascists are also anarchists, and their goals fit well with many Black Lives Matter activists’. The antifascists had been operating in the Pacific Northwest for decades as anti-racist skinheads, a kind of mirror to the more familiar yes-racism skinhead. These proto-Antifas went by the moniker Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice, or SHARP. Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter, a social-media-hashtag-turned-protest-movement started in the 2010s, had grown, primarily thanks to the warm embrace from glossy magazines and CEOs. Antifa wants the destruction of capitalism and the state’s monopoly on violence, while BLM wants a deep expansion of state power and potentially a new national anti-racism branch. So there were some differences.

But both groups hated the cops. Both groups wanted the abolition of police and prisons. The chant—“No good cops in a racist system”—worked for both of them. BLM’s corporate consultants needed a military arm, so they could work together for a little while.

There was a list of demands for the return of the neighborhood to the City of Seattle. They included abolition of imprisonment, along with de-gentrification and more equitable history lessons for elementary school children.

CHAZ leaders wanted autonomy, and they got it. They were free. The police were told not to enter these blocks. Signs hung at the border: No good cops no bad protestors and No cops no problem. They would create a localized anti-crime system. The anti-fascists were pulling off their ski masks, and everyone was getting along. Seattle was going all in.

It’s hard to tell when exactly CHAZ turned dark. Any troubles in the zone were downplayed. But online, shaky and dimly lit videos of CHAZ at night depicted big men passing out guns. Groups seemed to be doling out punishments, shoving people, screaming, shooting. But the videos were hard to interpret. And the only places that posted them were right-wing websites that pumped them out with blaring all-caps headlines. It was all SEATTLE DESTROYED BY LIBERALS. I didn’t trust any of it. So I got on a plane and flew to Seattle.

Faizel Khan, who watched the barricades grow stronger through the windows of his café, wasn’t opposed to the occupation per se. A gay man, he had moved from Texas to Seattle’s Capitol Hill to be somewhere welcoming and fun. He wanted a less racist country and believed in Black Lives Matter.

He called his shop Cafe Argento. Their tagline on Facebook: 12th Avenue’s Sexiest Coffee House. They made a great egg sandwich. For a while, things in his new city seemed alright. He supported Black Lives Matter because he supported progress.

His new city officials—that loose collective of anti-fascists and local Black Lives Matter leaders—held meetings to announce the community events. It was unclear how leadership of their new city was structured, who exactly was making decisions. But people were coming in from all over to see the new city, and for a little while the businesses were OK. It didn’t last.

When I met Faizel in July 2020, he was outside his café having a cigarette. I’d read his name in a lawsuit. Faizel and other small business owners and local residents were suing the city and the mayor. The city had abandoned business owners, the lawsuit asserted, and the mayor was aiding and abetting the insurgents. That city officials marched with the protestors and that the city helped build the barriers and provided Porta-Potties was bad, but also the city had stopped police and emergency services to the region. No fire trucks, no ambulances.

The lovely gay neighborhood might have been police-free but there was definitely policing. Half a dozen security teams wandered around the neighborhood, armed with handguns and rifles, open and concealed. Some of the teams wore official-looking private security uniforms. These were newly hired by local businesses and condos.

Others wore casual...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Bari Weiss • Common sense • Cynical Theories • Helen Pluckrose • Imran Kendi • Imran X Kendi • Imran X. Kendi • James Lindsay • New York Times • Robin DiAngelo • Wesley Yang |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80075-272-5 / 1800752725 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80075-272-6 / 9781800752726 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich