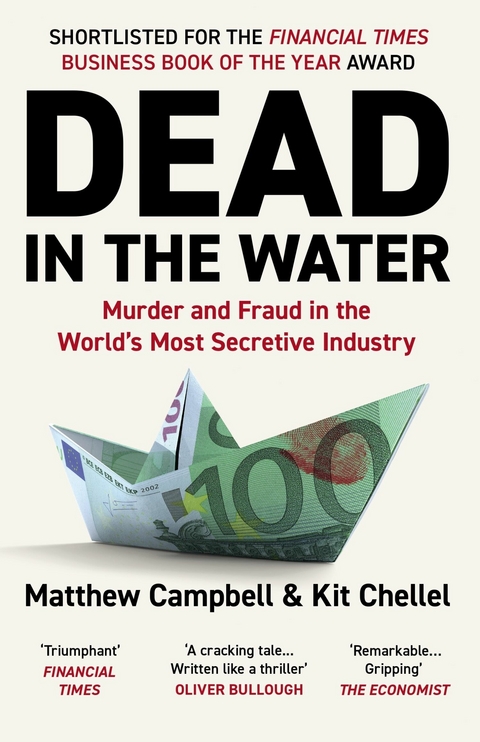

Dead in the Water (eBook)

288 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-254-9 (ISBN)

Matthew Campbell is a reporter and editor at BloombergBusinessweek. He has reported from more than 20 countries and is currently based in Singapore. Kit Chellel is a reporter at Bloomberg and a writer for Bloomberg Businessweek. His features have won numerous international awards and prompted investigations by the UK's market regulator. He is currently based in London

Matthew Campbell is a reporter and editor at BloombergBusinessweek. He has reported from more than 20 countries and is currently based in Singapore. Kit Chellel is a reporter at Bloomberg and a writer for Bloomberg Businessweek. His features have won numerous international awards and prompted investigations by the UK's market regulator. He is currently based in London

CHAPTER 1

A LUCKY LAND

In the middle of a spring night in 2011, Cynthia Mockett woke to the sound of gunshots. The rattle of automatic rifle fire was something she’d learned to tolerate over the years. But this sounded close, just outside her bedroom. Cynthia was sixty-four years old, a small, forceful woman with silvery hair and intense eyes. Her husband, David, was still asleep as she slid out of bed and crept over to the window. She could see the outlines of the old city of Aden laid out before her, its neat white buildings clinging to the rocky slopes of an extinct volcano, illuminated by the lights of the harbor beyond.

The villa that she and David had rented for several years in Yemen was situated a few blocks back from the ocean in Mualla, a district built by the British for colonial officials and soldiers, half a century before. As she knelt at the window, Cynthia breathed in the acrid smell of burning tires. Below her, crowds of young men were running through the darkness, yelling and shooting out streetlights, the muzzles of their rifles flashing with each report. It wasn’t clear if they were pursuing or being pursued. Suddenly, she heard David’s voice, bellowing at her from across the room. “What the bloody hell are you doing, Cynth? Get away from there!” She climbed back in bed and lay awake until the sky began to lighten, listening to the gunfire and, farther away, the claps of artillery echoing off the hillsides.

A little before eight o’clock, Cynthia opened the villa’s cast-iron gates and David eased his Lexus sport-utility vehicle into the pitted street, giving her a wave as he set out for his office near the Aden port. She looked around as he drove off. Children were playing amid the broken glass and vendors were hawking fruit, like nothing had happened the night before. At first Cynthia felt foolish, as if she’d imagined it all. But she couldn’t escape a feeling of unease. David had lived and worked in Yemen for more than a decade, a period in which Cynthia had shuttled regularly between the Arabian Peninsula and their home in England. Never an easy place, Aden had been noticeably disintegrating for months. They’d begun to talk about David’s plans for retirement, and spending more time with their grandchildren. Maybe now was the moment, Cynthia thought, for him to move back permanently.

The Mocketts had spent most of their forty-three years together in hot, dangerous places. They met when Cynthia was fifteen, living in a small town in Devon, a pastoral county in southwest England that’s also home to Europe’s largest naval base. He was a year younger, the friend of a cousin, and introduced himself by wolf-whistling in her direction. “Cheeky devil,” she said to herself. Later, he turned up at her bedroom window, refusing to leave until she agreed to go to the movies with him. Just before Christmas 1968, David put on a tie and Cynthia her best dress, and they hitched a ride to the registry office in a relative’s delivery van, sitting atop a pile of cabbages on their way to be married. David was a strapping six feet four, with a thunderous laugh and a way of dominating any room he walked into. In black-and-white photographs from the time, he looks like a young Sean Connery, broad-shouldered with a thick brow. His father worked for the Admiralty, the government department responsible for the Royal Navy, and he’d lived as a child in Sri Lanka and Gibraltar, gaining a taste for adventure that never left him. Cynthia thought he was the most exciting man she’d ever met. She still thought so four decades later, after he’d lost most of his hair and thickened around the middle.

As a sailor in the merchant navy, David went to sea for months at a time, which was hard on Cynthia, even if she knew the life she’d married into. It was unusual, especially in the 1970s, but David would invite her to join him on voyages whenever he could. She sailed with him once on a cargo ship carrying iron ore from India to Japan, spending much of the trip cleaning rust-colored dust out of their cabin. Some of the crew objected to the presence of a woman on board, but Cynthia didn’t much care. She had a quiet manner that masked a steely streak. She laughed easily, even at the bawdy humor of the young sailors, who treated her as a kind of surrogate mother. When the captain wasn’t on the bridge, David liked to let her steer the ship.

Money got tight when the Mocketts’ two daughters, Sarah and Rachael, were born, and in 1977 David took the offer of a well-paid job on land, as a port superintendent in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in the midst of the oil boom. By then he’d earned a master mariner’s certificate, qualifying him to skipper a vessel. Though he went ashore before being given his own command, he was still known thereafter as Captain Mockett.

Initially, Cynthia and the girls lived with him in a secure development for Westerners, insulated from the conservative strictures being enforced by Saudi religious police. But after a few years, Cynthia suspected she’d go mad with boredom if she had to spend many more days drinking gin and tonics with the other wives inside the walls of the compound. And she wanted their daughters to have a proper British education. She and the girls moved back to Devon, into a rambling stone cottage that everyone called the Vicarage. David stayed in the Middle East. He loved the people, and the rugged beauty of the coasts. Besides, the pay was good, and maintaining the Vicarage wasn’t cheap. When he was back in England, he would relax with a jigsaw puzzle and tell Cynthia about his adventures, like the time the Saudi king’s camels escaped and rampaged through the port. Some of them had to be retrieved thirty miles away.

In 1998, David took a position as a marine surveyor in Yemen. Surveyors play a vital, unsung role in seaborne trade, providing independent analyses of marine mishaps, helping to pinpoint their cause and informing decisions on compensation. It would be Mockett’s job to inspect vessels and cargo passing through Yemeni waters, on behalf of the various merchants, traders, bankers, shipowners, and insurance companies who required his services. One day he might cast his expert eye over a tanker with engine trouble carrying oil from Kuwait to Texas; the next a damaged consignment of steel rebar bound for Rotterdam. Even in an age of largely automated container vessels and real-time satellite navigation, such incidents occurred at sea constantly, and with a shortage of skilled surveyors in the region there was good money to be made.

Yet moving to the poorest nation in the Middle East was a daunting proposition. Then as now, Yemen could make a strong claim to being the least governable place on earth. And many have tried to govern it, since the country sits on an important geopolitical choke point between Saudi Arabia and the Horn of Africa, abutting the main shipping route from Asia to Europe. The Ottoman Turks came in the sixteenth century, trying to bribe the local sheikhs into loyalty, only to be beaten back again and again by fierce highland tribes. One Turkish official described mountains that “pierce the clouds, a place where there was only pain.” Legend has it that Ottoman troops had to be chained to their ships to force them into service in Yemen’s battlegrounds.

Next came the British, who set their sights on Aden as a way station for ships sailing to and from the Indian colonies. In 1837, an attack on a Britishflagged vessel provided a pretext for the East India Company to seize what was then a fishing village. British investment helped bring a degree of prosperity to southern Yemen, especially after the Suez Canal opened up the trade route through Egypt, and Aden became one of the most important ports in the Empire, a gateway between East and West. Colonial administrators installed a clocktower known as “Little Ben,” a statue of Queen Victoria, and a Western-style bureaucracy. Once again, though, the region’s inhabitants vigorously asserted their independence. Aden was so rough that it became a punishment posting for army regiments that had fallen into disgrace. A Scottish officer stationed there in the 1850s complained about the prickly heat, the howling of wild dogs, and an “aspect of desolation which pervades the place.”

In the 1960s, as the British were being driven out by militants armed with grenades and machine guns, Egyptian troops were embroiled in a bloody campaign in the north of Yemen, in what Egypt’s president Gamal Abdel Nasser called “my Vietnam.” After the British left, a Kremlin-backed socialist regime took control of the south, which nearly came apart in a bloody civil conflict in the 1980s. Russians stationed in Aden were forced to flee the slaughter, ignominiously, on the royal yacht Britannia, which had been sailing nearby. Even fellow Marxists found the violence excessive. “When are you people going to stop killing each other?” Cuban leader Fidel Castro grumbled to a local counterpart.

By the time David Mockett settled there in the late 1990s, Yemen’s southern and northern halves were united under a lavishly corrupt military ruler called Ali Abdullah Saleh. The country was still roiling and chaotic, overflowing with Russian firearms, aggressive tribal militias, and, increasingly, Islamic extremists. The president’s security forces offered a haven to jihadis returning from Afghanistan, including associates of Osama Bin Laden and his growing Al Qaeda network, even as Saleh tried to persuade the outside world that he was a willing partner,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.5.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Unternehmensführung / Management | |

| Schlagworte | 2022 Financial Times Business Book of the Year Award • books of the year • brillante virtuoso • Crime • economy • financial times book of the year • financial times books of the year • financial times business book of the year • kit chellel • Matthew Campbell • Patrick Radden Keefe • shipping • shipping industry • Somalia • the times books of the year • Trade • waterstones best books • Yemen |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-254-3 / 1838952543 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-254-9 / 9781838952549 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 7,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich