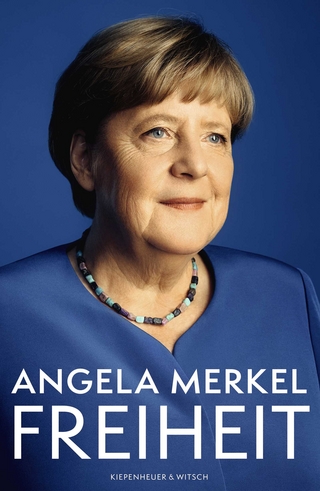

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

The Belknap Press (Verlag)

978-0-674-43000-6 (ISBN)

Piketty shows that modern economic growth and the diffusion of knowledge have allowed us to avoid inequalities on the apocalyptic scale predicted by Karl Marx. But we have not modified the deep structures of capital and inequality as much as we thought in the optimistic decades following World War II. The main driver of inequality—the tendency of returns on capital to exceed the rate of economic growth—today threatens to generate extreme inequalities that stir discontent and undermine democratic values. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, Piketty says, and may do so again.

A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today.

Thomas Piketty is Professor at the Paris School of Economics.

Arthur Goldhammer received the French–American Translation Prize in 1990 for his translation of A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution.

Acknowledgments

Introduction

I. Income and Capital

1. Income and Output

2. Growth: Illusions and Realities

II. The Dynamics of the Capital/Income Ratio

3. The Metamorphoses of Capital

4. From Old Europe to the New World

5. The Capital/Income Ratio over the Long Run

6. The Capital–Labor Split in the Twenty-First Century

III. The Structure of Inequality

7. Inequality and Concentration: Preliminary Bearings

8. Two Worlds

9. Inequality of Labor Income

10. Inequality of Capital Ownership

11. Merit and Inheritance in the Long Run

12. Global Inequality of Wealth in the Twenty-First Century

IV. Regulating Capital in the Twenty-First Century

13. A Social State for the Twenty-First Century

14. Rethinking the Progressive Income Tax

15. A Global Tax on Capital

16. The Question of the Public Debt

Conclusion

Notes

Contents in Detail

List of Tables and Illustrations*

Index

* Tables and Illustrations

Tables

Table 1.1. Distribution of world GDP, 2012

Table 2.1. World growth since the Industrial Revolution

Table 2.2. The law of cumulated growth

Table 2.3. Demographic growth since the Industrial Revolution

Table 2.4. Employment by sector in France and the United States, 1800–2012

Table 2.5. Per capita output growth since the Industrial Revolution

Table 3.1. Public wealth and private wealth in France in 2012

Table 5.1. Growth rates and saving rates in rich countries, 1970–2010

Table 5.2. Private saving in rich countries, 1970–2010

Table 5.3. Gross and net saving in rich countries, 1970–2010

Table 5.4. Private and public saving in rich countries, 1970–2010

Table 7.1. Inequality of labor income across time and space

Table 7.2. Inequality of capital ownership across time and space

Table 7.3. Inequality of total income (labor and capital) across time and space

Table 10.1. The composition of Parisian portfolios, 1872–1912

Table 11.1. The age–wealth profile in France, 1820–2010

Table 12.1. The growth rate of top global wealth, 1987–2013

Table 12.2. The return on the capital endowments of US universities, 1980–2010

Illustrations

Figure I.1. Income inequality in the United States, 1910–2010

Figure I.2. The capital/income ratio in Europe, 1870–2010

Figure 1.1. The distribution of world output, 1700–2012

Figure 1.2. The distribution of world population, 1700–2012

Figure 1.3. Global inequality 1700–2012: divergence then convergence?

Figure 1.4. Exchange rate and purchasing power parity: euro/dollar

Figure 1.5. Exchange rate and purchasing power parity: euro/yuan

Figure 2.1. The growth of world population, 1700–2012

Figure 2.2. The growth rate of world population from Antiquity to 2100

Figure 2.3. The growth rate of per capita output since the Industrial Revolution

Figure 2.4. The growth rate of world per capita output from Antiquity to 2100

Figure 2.5. The growth rate of world output from Antiquity to 2100

Figure 2.6. Inflation since the Industrial Revolution

Figure 3.1. Capital in Britain, 1700–2010

Figure 3.2. Capital in France, 1700–2010

Figure 3.3. Public wealth in Britain, 1700–2010

Figure 3.4. Public wealth in France, 1700–2010

Figure 3.5. Private and public capital in Britain, 1700–2010

Figure 3.6. Private and public capital in France, 1700–2010

Figure 4.1. Capital in Germany, 1870–2010

Figure 4.2. Public wealth in Germany, 1870–2010

Figure 4.3. Private and public capital in Germany, 1870–2010

Figure 4.4. Private and public capital in Europe, 1870–2010

Figure 4.5. National capital in Europe, 1870–2010

Figure 4.6. Capital in the United States, 1770–2010

Figure 4.7. Public wealth in the United States, 1770–2010

Figure 4.8. Private and public capital in the United States, 1770–2010

Figure 4.9. Capital in Canada, 1860–2010

Figure 4.10. Capital and slavery in the United States

Figure 4.11. Capital around 1770–1810: Old and New World

Figure 5.1. Private and public capital: Europe and the United States, 1870–2010

Figure 5.2. National capital in Europe and America, 1870–2010

Figure 5.3. Private capital in rich countries, 1970–2010

Figure 5.4. Private capital measured in years of disposable income

Figure 5.5. Private and public capital in rich countries, 1970–2010

Figure 5.6. Market value and book value of corporations

Figure 5.7. National capital in rich countries, 1970–2010

Figure 5.8. The world capital/income ratio, 1870–2100

Figure 6.1. The capital–labor split in Britain, 1770–2010

Figure 6.2. The capital–labor split in France, 1820–2010

Figure 6.3. The pure return on capital in Britain, 1770–2010

Figure 6.4. The pure rate of return on capital in France, 1820–2010

Figure 6.5. The capital share in rich countries, 1975–2010

Figure 6.6. The profit share in the value added of corporations in France, 1900–2010

Figure 6.7. The share of housing rent in national income in France, 1900–2010

Figure 6.8. The capital share in national income in France, 1900–2010

Figure 8.1. Income inequality in France, 1910–2010

Figure 8.2. The fall of rentiers in France, 1910–2010

Figure 8.3. The composition of top incomes in France in 1932

Figure 8.4. The composition of top incomes in France in 2005

Figure 8.5. Income inequality in the United States, 1910–2010

Figure 8.6. Decomposition of the top decile, United States, 1910–2010

Figure 8.7. High incomes and high wages in the United States, 1910–2010

Figure 8.8. The transformation of the top 1 percent in the United States

Figure 8.9. The composition of top incomes in the United States in 1929

Figure 8.10. The composition of top incomes in the United States, 2007

Figure 9.1. Minimum wage in France and the United States, 1950–2013

Figure 9.2. Income inequality in Anglo-Saxon countries, 1910–2010

Figure 9.3. Income inequality in Continental Europe and Japan, 1910–2010

Figure 9.4. Income inequality in Northern and Southern Europe, 1910–2010

Figure 9.5. The top decile income share in Anglo-Saxon countries, 1910–2010

Figure 9.6. The top decile income share in Continental Europe and Japan, 1910–2010

Figure 9.7. The top decile income share in Europe and the United States, 1900–2010

Figure 9.8. Income inequality in Europe versus the United States, 1900–2010

Figure 9.9. Income inequality in emerging countries, 1910–2010

Figure 10.1. Wealth inequality in France, 1810–2010

Figure 10.2. Wealth inequality in Paris versus France, 1810–2010

Figure 10.3. Wealth inequality in Britain, 1810–2010

Figure 10.4. Wealth inequality in Sweden, 1810–2010

Figure 10.5. Wealth inequality in the United States, 1810–2010

Figure 10.6. Wealth inequality in Europe versus the United States, 1810–2010

Figure 10.7. Return to capital and growth: France, 1820–1913

Figure 10.8. Capital share and saving rate: France, 1820–1913

Figure 10.9. Rate of return versus growth rate at the world level, from Antiquity until 2100

Figure 10.10. After tax rate of return versus growth rate at the world level, from Antiquity until 2100

Figure 10.11. After tax rate of return versus growth rate at the world level, from Antiquity until 2200

Figure 11.1. The annual inheritance flow as a fraction of national income, France, 1820–2010

Figure 11.2. The mortality rate in France, 1820–2100

Figure 11.3. Average age of decedents and inheritors, France, 1820–2100

Figure 11.4. Inheritance flow versus mortality rate, France, 1820–2010

Figure 11.5. The ratio between average wealth at death and average wealth of the living, France, 1820–2010

Figure 11.6. Observed and simulated inheritance flow, France, 1820–2100

Figure 11.7. The share of inherited wealth in total wealth, France, 1850–2100

Figure 11.8. The annual inheritance flow as a fraction of household disposable income, France, 1820–2010

Figure 11.9. The share of inheritance in the total resources (inheritance and work) of cohorts born in 1790–2030

Figure 11.10. The dilemma of Rastignac for cohorts born in 1790–2030

Figure 11.11. Which fraction of a cohort receives in inheritance the equivalent of a lifetime labor income?

Figure 11.12. The inheritance flow in Europe, 1900–2010

Figure 12.1. The world’s billionaires according to Forbes, 1987–2013

Figure 12.2. Billionaires as a fraction of global population and wealth, 1987–2013

Figure 12.3. The share of top wealth fractiles in world wealth, 1987–2013

Figure 12.4. The world capital/income ratio, 1870–2100

Figure 12.5. The distribution of world capital, 1870–2100

Figure 12.6. The net foreign asset position of rich countries

Figure 13.1. Tax revenues in rich countries, 1870–2010

Figure 14.1. Top income tax rates, 1900–2013

Figure 14.2. Top inheritance tax rates, 1900–2013

“Anyone remotely interested in economics needs to read Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century.”—Matthew Yglesias, Slate

“This book is not only the definitive account of the historical evolution of inequality in advanced economies, it is also a magisterial treatise on capitalism’s inherent dynamics.”—Dani Rodrik, Institute for Advanced Study

“In this magisterial work, Thomas Piketty has performed a great service to the academy and to the public. He has written a pioneering book that is at once thoughtful, measured, and provocative. The force of his case rests not on a diatribe or a political agenda, but on carefully collected and analyzed data and reasoned thought. The book should have a major impact on our discussions of contemporary inequality and its meaning for our democratic institutions and ideals. I can only marvel at Piketty’s discipline and rigor in researching and writing it.”—Rakesh Khurana, Harvard Business School

“The book of the season.”—Telerama

“Outstanding… A political and theoretical bulldozer.”—Mediapart

“An explosive argument.”—Liberation

“A seminal book on the economic and social evolution of the planet… A masterpiece.”—Emmanuel Todd, Marianne

“Piketty, a prominent economist, explains the tendency in mature societies for wealth to concentrate in a few hands.”—Amy Merrick, The New Yorker

“Defies left and right orthodoxy by arguing that worsening inequality is an inevitable outcome of free market capitalism… [It] suggests that traditional liberal government policies on spending, taxation and regulation will fail to diminish inequality… Without what [Piketty] acknowledges is a politically unrealistic global wealth tax, he sees the United States and the developed world on a path toward a degree of inequality that will reach levels likely to cause severe social disruption. Final judgment on Piketty’s work will come with time—a problem in and of itself, because if he is right, inequality will worsen, making it all the more difficult to take preemptive action.”—Thomas B. Edsall, The New York Times

"It is a great work, a fearsome beast of analysis stuffed with an awesome amount of empirical data, and will surely be a landmark study in economics.”—The Week

“The book aims to revolutionize the way people think about the economic history of the past two centuries. It may well manage the feat… It is, first and foremost, a very detailed look at 200 years’ worth of data on the distribution of income and wealth across the rich world (with some figures for large emerging markets also included). This mountain of data allows Piketty to tell a simple and compelling story… The database on which the book is built is formidable, and it is difficult to dispute his call for a new perspective on the modern economic era, whether or not one agrees with his policy recommendations… We are all used to sneering at communism because of its manifest failure to deliver the sustained rates of growth managed by market economies. But Marx’s original critique of capitalism was not that it made for lousy growth rates. It was that a rising concentration of wealth couldn’t be sustained politically. Ultimately, those of us who would like to preserve the market system need to grapple with that sort of dynamic, in the context of the worrying numbers on inequality that Piketty presents.”—The Economist

“Groundbreaking…The usefulness of economics is determined by the quality of data at our disposal. Piketty’s new volume offers a fresh perspective and a wealth of newly compiled data that will go a long way in helping us understand how capitalism actually works.”—Christopher Matthews, Fortune.com

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.4.2014 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Arthur Goldhammer |

| Zusatzinfo | 96 graphs, 18 tables |

| Verlagsort | Cambridge, Mass. |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Maße | 168 x 244 mm |

| Gewicht | 1207 g |

| Einbandart | gebunden |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Wirtschaftsgeschichte |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Wirtschaft ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Finanzierung | |

| Wirtschaft ► Volkswirtschaftslehre ► Wirtschaftspolitik | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-674-43000-X / 067443000X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-674-43000-6 / 9780674430006 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

aus dem Bereich