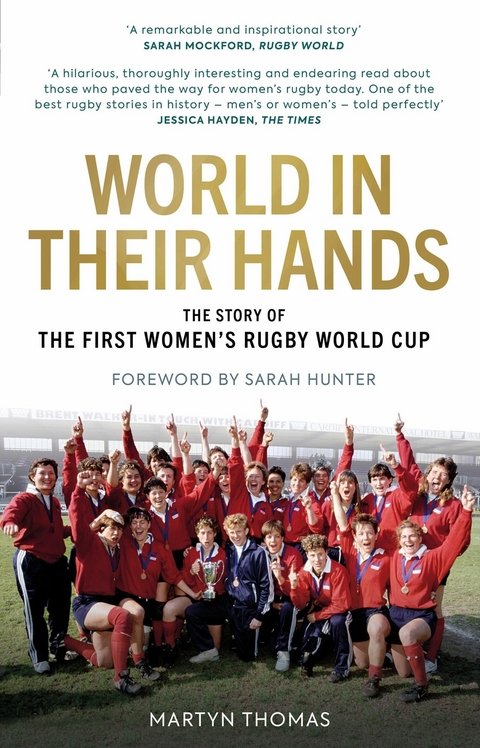

World in their Hands (eBook)

320 Seiten

Polaris (Verlag)

978-1-913538-94-1 (ISBN)

World in their Hands recounts the remarkable events that led to a group of friends from south-west London staging the inaugural Women's Rugby World Cup in 1991. The tournament was held just 13 years after teams from University College London and King's contested a match that catalysed the growth of the women's game in the UK, and the organisers overcame myriad obstacles before, during and after the World Cup. Those challenges, which included ingrained misogyny, motherhood, a recession, the Gulf War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, provide a fitting framing device for a book that celebrates female achievement in the face of adversity.

Although ostensibly a story about women's rugby, this is a tale that has rare crossover appeal. It is not only the account of a group of inspirational women who took on the institutional misogyny that existed in rugby clubs across the globe to put on a first ever Women's Rugby World Cup. It is also the compelling and relatable tale of how those women, their peers and others in the generations before them, reshaped the idea of what it means to be a woman, finding acceptance and friendship on boggy rugby pitches. At the time, with the men's game tying itself up in knots about professionalism and apartheid, these women were a breath of fresh air. Three decades on, their achievements deserve to be highlighted to a wider audience.

Martyn Thomas is a freelance sports journalist who works with World Rugby as an editorial consultant. He has written extensively about the history of the women's Rugby World Cup for World Rugby and for Rugby World. Having begun his career at The Guardian and worked as rugby editor for ESPN, he has also written for RugbyPass, Mirror Online, Eurosport, Sport360 and the official Rugby World Cup 2019 match programmes. Sarah Hunter is an English rugby union player. She has represented England since the 2010 Women's Rugby World Cup and currently captains the team.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.9.2022 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Sarah Hunter |

| Zusatzinfo | 16pp colour & b/w plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Ballsport |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Sportwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | 2022 • 2025 • Adversity • Alex Matthews • Alice Cooper • Ali Donnelly • Alison Kervin • All Blacks • Australia • Bryony Cleall • Champions • Deborah Griffin • Emily Scarratt • Empowering • endearing • England • Euro 2022 • Fiona Tomas • Five Nations • France • Friendship • Grand slam • Gulf War • Hardback • Helena Rowland • History of sport • Holly Aitchison • Inspirational • Ireland • Jess Breach • Jessica Hayden • Jim Hamilton • lionesses • Maggie Alphonsi • Marlie Packer • Martyn Thomas • Mary Forsyth • misogyny • Natasha Hunt • New Zealand • New Zealand 2022 • Poppy Cleall • red roses • rfu • rivalry • rivals • Rugby • rugby gift • rugby history • Rugby Pod • Rugby Union • Rugby World • rugby world cup • Sarah Beckett • Sarah Bern • Sarah Hunter • Sarah Mockford • Scotland • Scottish • Scrumqueens • Scrum Queens • Shaunagh Brown • Silver Ferns • Simon Middleton • Six Nations • South Africa • Soviet Union • Sport Gift • SRU • Stephen Jones • Sue Dorrington • The Times • Twickenham • UK • University College London • USA • USSR • Wales • Women • Women's history • women’s rugby • Women's Six Nations • women’s sport • Women's Sport • Women's World Cup • World Cup • World Cup 2023 • Zoe Aldcroft • Zoe Harrison |

| ISBN-10 | 1-913538-94-X / 191353894X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-913538-94-1 / 9781913538941 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich