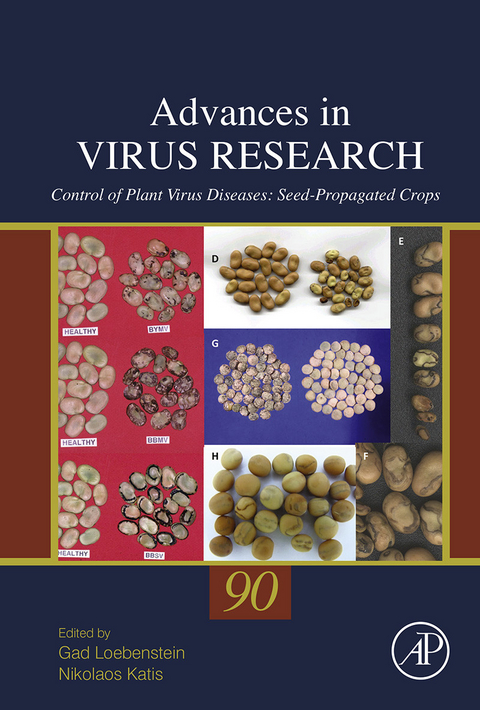

The first review series in virology and published since 1953, Advances in Virus Research covers a diverse range of in-depth reviews, providing a valuable overview of the field. The series of eclectic volumes are valuable resources to virologists, microbiologists, immunologists, molecular biologists, pathologists, and plant researchers.

Volume 90 features articles on control of plant virus diseases.

- Contributions from leading authorities

- Comprehensive reviews for general and specialist use

- First and longest-running review series in virology

The first review series in virology and published since 1953, Advances in Virus Research covers a diverse range of in-depth reviews, providing a valuable overview of the field. The series of eclectic volumes are valuable resources to virologists, microbiologists, immunologists, molecular biologists, pathologists, and plant researchers. Volume 90 features articles on control of plant virus diseases. Contributions from leading authorities Comprehensive reviews for general and specialist use First and longest-running review series in virology

Front Cover 1

Control of Plant Virus Diseases: Seed-Propagated Crops 4

Copyright 5

Contents 6

Contributors 10

Preface 12

Chapter One: Management of Air-Borne Viruses by ``Optical Barriers´´ in Protected Agriculture and Open-Field Crops 14

1. Introduction 15

2. The Insects Vision Apparatus 15

2.1. UV vision and insects behavior 16

2.1.1. Effect of UV on insects dispersal and propagation 17

2.1.2. UV stimulated phototaxis of insects 18

2.1.3. Effect of UV reflection 19

3. Use of UV-Absorbing Cladding Materials for Greenhouse Protection Against the Spread of Insect Pests and Virus Diseases 20

3.1. Spectral transmission properties of UV-absorbing cladding materials 20

3.2. Effect of UV-absorbing films on the immigration of insect pests into greenhouses 22

3.3. Effect of UV filtration on the spread of insect-vectored virus diseases 24

3.4. Effect of UV filtration on crop plants 25

3.5. Effect of UV filtration on pollinators 27

3.6. Effect of UV filtration on insect natural enemies 29

3.7. Effect of UV-absorbing screens on the immigration of insect pests into greenhouses 30

3.8. Mode of action of UV-absorbing greenhouse cladding materials 31

4. Sticky Traps for Monitoring and Insects Mass Trapping 32

5. Soil Mulches 33

6. Reflective and Colored Shading Nets 36

7. Reflective Films Formed by Whitewashes 37

8. Prospects and Outlooks 39

References 39

Chapter Two: Transgenic Resistance 48

1. Introduction 49

2. Viral Protein-Mediated Resistance 50

2.1. Coat protein-mediated resistance 50

2.2. Replicase-mediated resistance 58

2.3. Movement protein-mediated resistance 71

2.4. Other viral protein-mediated resistance 73

2.4.1. Rep protein-mediated resistance 73

2.4.2. NIa protease-mediated resistance 73

2.4.3. P1 protein-mediated resistance 75

2.4.4. HCPro-mediated resistance 75

2.4.5. Other viral gene-mediated resistance 76

3. Viral RNA-Mediated Resistance 77

3.1. Noncoding single-stranded RNAs 78

3.1.1. Noncoding regions of viral genomes 78

3.1.2. Nontranslatable sense RNAs 79

3.1.3. Antisense RNAs 81

3.1.3.1. DNA viruses 81

3.1.3.2. RNA viruses 82

3.2. Satellite RNA 85

3.3. Defective-interfering RNAs/DNAs 87

3.4. Ribozymes 88

3.5. dsRNAs and hpRNAs 88

3.5.1. Cassava expressing hpRNAs 89

3.5.2. Citrus expressing hpRNAs 90

3.5.3. Cucurbits expressing hpRNAs 90

3.5.4. Legumes expressing hpRNAs 90

3.5.5. Maize expressing hpRNAs 91

3.5.6. N. benthamiana expressing hpRNAs 91

3.5.7. Potato expressing hpRNAs 93

3.5.8. Prunus species expressing hpRNAs 93

3.5.9. Rice expressing hpRNAs 94

3.5.10. Soybean expressing hpRNAs 95

3.5.11. Sugar beet expressing hpRNAs 95

3.5.12. Sweet potato expressing hpRNAs 96

3.5.13. Tobacco expressing hpRNAs 96

3.5.14. Tomato expressing hpRNAs 98

3.5.15. Wheat expressing hpRNAs 98

3.5.16. Other plant species expressing hpRNAs 98

3.5.17. Various parameters affecting resistance 99

3.6. Artificial microRNAs 102

4. Nonviral-Mediated Resistance 106

4.1. Nucleases 106

4.2. Antiviral inhibitor proteins 108

4.2.1. Ribosome-inactivating proteins 108

4.2.2. Virus replication inhibitor protein 109

4.2.3. Artificial zinc finger protein 110

4.2.4. Peptide aptamers 110

4.2.5. Cationic peptides 111

4.3. Plantibodies 112

5. Host-Derived Resistance 114

5.1. Dominant resistance genes 114

5.2. Recessive resistance genes 116

5.3. Defense response factors 117

6. Conclusions and Perspectives 119

Acknowledgments 121

References 122

Chapter Three: Management of Whitefly-Transmitted Viruses in Open-Field Production Systems 160

1. Introduction 161

2. Whiteflies and the Viruses They Transmit 162

2.1. The whiteflies 162

2.2. The viruses 163

2.2.1. Betaflexiviridae, Carlavirus 164

2.2.2. Closteroviridae, Crinivirus 164

2.2.3. Geminiviridae, Begomovirus 165

2.2.4. Potyviridae, Ipomovirus 166

2.2.5. Secoviridae, Torradovirus 166

3. Management of Whitefly-Transmitted Viruses Using Pesticides 167

4. Management of Whitefly-Transmitted Viruses Using Cultural Practices 172

4.1. Plastic soil mulches 172

4.2. Virus-free seed/planting material 175

4.3. Crop placement-In space 175

4.4. Crop placement-In time 176

4.5. Trap crops 177

4.6. Intercropping 178

4.7. Physical barriers 178

4.8. Physical traps 179

4.9. Conclusions 180

5. Genetic Resistance 180

5.1. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus 181

5.2. Development of a controlled whitefly-mediated inoculation system 183

5.3. When should we inoculate? 184

5.4. Breeding tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) for resistance to TYLCV 186

5.5. Effect of TYLCV-resistant genotypes on virus epidemiology 188

5.6. Bean (P. vulgaris) resistance to TYLCV 190

5.7. Genetic resistance to the whitefly 192

6. Case Study1: Managing Begomoviruses and Ipomoviruses in Cassava 193

6.1. Principal components of management strategies for cassava viruses 193

6.2. Host plant resistance to cassava viruses 194

6.3. Phytosanitation 194

6.4. Other cultural practices 195

6.5. Vector control 196

6.6. Integrated control strategies 197

7. Case Study2: Management of Criniviruses 198

7.1. CYSDV: Managing crinivirus infection in the field 200

7.2. Identification and management of crop and weed reservoir hosts 201

7.3. Genetic resistance to the virus 201

7.4. Crinivirus management in transplanted crops 203

7.5. Summary 203

8. Concluding Remarks 204

References 205

Chapter Four: Control of Plant Virus Diseases in Cool-Season Grain Legume Crops 220

1. Introduction 221

2. Surveys, Importance, Losses, Economics in Relation to Virus Control and Control Methods 222

3. Host Resistance 234

3.1. Selection and breeding for virus resistance 234

3.2. Resistance to potyviruses 234

3.3. Resistance to luteo-, polero-, and nanoviruses 239

3.4. Resistance to alphamo- and cucumoviruses 240

3.5. Breeding for vector resistance 241

3.6. Transgenic virus resistance 241

4. Phytosanitary Measures 242

4.1. Healthy seeds 242

4.2. Roguing 243

4.3. Removal of wild hosts, volunteers, and crop residues 243

5. Cultural Practices 243

5.1. Isolation, avoiding successive side-by-side plantings, and crop rotation 243

5.2. Early canopy development and high plant density 244

5.3. Sowing date 244

5.4. Narrow row spacing and high seeding rate 245

5.5. Groundcover 245

5.6. Early maturing cultivars 246

5.7. Nonhost barrier, tall nonhost cover crop, and mixed cropping with a nonhost 246

5.8. Planting upwind or using windbreaks 247

6. Chemical Control 247

6.1. Nonpersistent viruses 248

6.2. Persistent viruses 248

7. Biological Control 249

8. Integrated Approaches 249

9. Implications of Climate Change and New Technologies 252

10. Conclusions 252

References 254

Chapter Five: Control of Cucurbit Viruses 268

1. Introduction 269

2. Growing Healthy Seeds in a Healthy Environment 273

2.1. Use of healthy seeds and seedlings 274

2.1.1. Modes of seed transmission 275

2.1.2. How to prevent seed transmission 276

2.1.3. Seedling quality 276

2.2. Limiting virus sources near cucurbit crops 277

2.2.1. Weeds: Important virus sources 277

2.2.2. Other potential virus sources 278

2.2.3. Avoiding overlapping crops 278

3. Altering the Activity of Vectors 279

3.1. Actions against viruses transmitted by manual operations 280

3.2. Actions against soil-borne viruses 280

3.3. Actions against insect-borne viruses 280

3.3.1. Protected crops 281

3.3.2. Field crops 282

4. Making Cucurbits Resistant to Viruses 285

4.1. Grafting on resistant rootstock 286

4.2. Mild-strain cross-protection 286

4.2.1. Cross-protection against ZYMV 287

4.2.2. Other mild strains of cucurbit viruses 287

4.2.3. Limitations of cross-protection 288

4.3. Conventional breeding for resistance 288

4.3.1. Diversity of virus-resistance mechanisms in cucurbits 289

4.3.2. Resistance durability, an important issue 293

4.4. Transgenic resistance in cucurbits 295

4.4.1. Diversity of transgenic resistances 296

4.4.2. Commercial use of transgenic virus-resistant cultivars 297

4.4.3. Risk assessment studies 297

5. Concluding Remarks 299

References 302

Chapter Six: Virus Diseases of Peppers (Capsicum spp.) and Their Control 310

1. Introduction 311

2. The Main Viruses Infecting Peppers 312

2.1. Aphid-transmitted viruses 312

2.1.1. Potyviruses 312

2.1.2. Cucumoviruses 315

2.1.3. Poleroviruses 316

2.1.4. Other aphid-transmitted viruses of pepper 317

2.2. Whitefly-transmitted viruses 318

2.2.1. Crinivirus 318

2.2.2. Begomoviruses 318

2.3. Thrips-transmitted viruses 322

2.3.1. Tospoviruses 322

2.3.2. Ilarviruses 325

2.4. Viruses of pepper with other invertebrate vectors 326

2.5. Viruses not transmitted by invertebrate vectors 326

2.5.1. Tobamoviruses 326

2.5.2. Tombusvirus 327

3. Management of Viruses Infecting Peppers 327

3.1. Cultural and phytosanitary practices 327

3.2. Vector management with insecticides 333

3.3. Mild-strain cross-protection 334

3.4. Host plant resistance against viruses 335

3.4.1. Resistance to CMV 335

3.4.2. Resistance to potyviruses 340

3.4.3. Resistance to tospoviruses 342

3.4.4. Resistance against begomoviruses 343

3.4.5. Resistance to tobamoviruses 344

3.5. Natural resistance to virus vectors 346

3.6. Transgenic resistance 347

4. Discussion and Conclusions 349

References 356

Chapter Seven: Control of Virus Diseases in Soybeans 368

1. Introduction 369

2. Soybean Mosaic Virus 371

2.1. Biology 371

2.2. Management 378

3. Bean Pod Mottle Virus 380

3.1. Biology 380

3.2. Management 382

4. Soybean Vein Necrosis Virus 383

4.1. Biology 383

4.2. Management 383

5. Tobacco Ringspot Virus 384

5.1. Biology 384

5.2. Management 385

6. Soybean Dwarf Virus 386

6.1. Biology 386

6.2. Management 387

7. Peanut Mottle Virus 388

7.1. Biology 388

7.2. Management 388

8. Peanut Stunt Virus 389

8.1. Biology 389

8.2. Management 389

9. Alfalfa Mosaic Virus 390

9.1. Biology 390

9.2. Management 391

10. Management: Present and Prospects 391

Acknowledgments 395

References 396

Chapter Eight: Control of Virus Diseases in Maize 404

1. Introduction 405

2. Virus Diseases of Maize 405

2.1. Maize dwarf mosaic 407

2.2. Maize streak 408

2.3. Maize chlorotic dwarf 409

2.4. Maize mosaic 409

2.5. Maize stripe 410

2.6. Maize rayado fino (maize fine stripe) 410

2.7. Maize rough dwarf 411

2.8. Mal de Río Cuarto 412

2.9. Maize chlorotic mottle and corn (maize) lethal necrosis 413

2.10. High Plains disease 414

3. Disease Emergence and Control 415

3.1. Removal of pathogen reservoirs 415

3.2. Distrupting vector-maize interactions 417

3.3. Pathogen resistance in maize 417

4. Development of Virus-Resistant Crops 422

4.1. Screening methods 423

4.2. Virus isolates and disease development 424

5. Genetics of Resistance to Virus Diseases 425

5.1. Breeding methods and results 427

6. Toward Understanding Virus Resistance Mechanisms in Maize 428

6.1. Mechanisms of virus resistance in maize 429

7. Conclusion 431

Acknowledgments 431

References 431

Chapter Nine: Tropical Food Legumes: Virus Diseases of Economic Importance and Their Control 444

1. Introduction 445

2. Virus Diseases of Major Food Legumes 447

2.1. Soybean 447

2.1.1. Mosaic 452

2.1.2. Dwarf 454

2.1.3. Bud blight 455

2.1.4. Brazilian bud blight 456

2.1.5. Yellow mosaic due to begomoviruses 457

2.2. Groundnut 458

2.2.1. Rosette 458

2.2.2. Spotted wilt 461

2.2.3. Bud necrosis 463

2.2.4. Stem necrosis 465

2.2.5. Clump 466

2.2.6. Mottle and stripe 467

2.2.7. Yellow mosaic 469

2.3. Common bean 469

2.3.1. Common mosaic and black root 469

2.3.2. Golden mosaic, golden yellow mosaic, and dwarf mosaic 471

2.3.3. Mosaic due to CMV 473

2.4. Cowpea 474

2.5. Pigeonpea 477

2.5.1. Sterility mosaic 477

2.5.2. Yellow mosaic 480

2.6. Mungbean and urdbean 481

2.6.1. Yellow mosaic 481

2.6.2. Leaf curl 483

2.6.3. Leaf crinkle 484

2.7. Chickpea 484

2.7.1. Stunt 484

2.7.2. Chlorotic dwarf 485

2.8. Pea 487

2.8.1. Mosaic caused by PSbMV and BYMV 487

2.8.2. Enation mosaic 488

2.8.3. Top yellows 488

2.9. Faba bean 488

2.9.1. Necrotic yellows and necrotic stunt 488

2.9.2. Leaf roll 489

2.9.3. Mosaic and necrosis 489

2.9.4. Mottle 490

2.10. Lentil 490

2.10.1. Yellows and stunt 490

2.10.2. Mosaic and mottle 491

3. Virus Diseases of Minor Food Legumes 492

3.1. Hyacinth bean 492

3.2. Horse gram 493

3.3. Lima bean 493

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects 494

Acknowledgments 495

References 495

Index 520

Management of Air-Borne Viruses by “Optical Barriers” in Protected Agriculture and Open-Field Crops

Yehezkel Antignus*,1 * Plant Pathology and Weed Research Department, ARO, The Volcani Center, Bet Dagan, Israel

1 Corresponding author: email address: antignus@volcani.agri.gov.il

Abstract

The incurable nature of viral diseases and the public awareness to the harmful effects of chemical pest control to the environment and human health led to the rise of the integrated pest management (IPM) concept. Cultural control methods serve today as a central pivot in the implementation of IPM. This group of methods is based on the understanding of the complex interactions between disease agents and their vectors as well as the interactions between the vectors and their habitat. This chapter describes a set of cultural control methods that are based on solar light manipulation in a way that interferes with vision behavior of insects, resulting in a significant crop protection against insect pests and their vectored viruses.

Keywords

IPM

UV vision of insects

UV effects on insects behavior

UV-absorbing films and greenhouse protection against insects

Sticky yellow traps

Reflective soil mulches

Whitewashes

Colored shading nets

1 Introduction

Insect-borne plant viruses may cause severe losses to many annual and perennial crops of a high economic value. Insect vectors of plant viruses are found in 7 of the 32 orders of the class Insecta and are therefore responsible for severe epidemics that form a threat to the world's agricultural industry. Insect vectors transmit plant viruses by four major transmission modes that are supported by a number of viral and insect proteins (Raccah & Fereres, 2009). The obligatory parasitism of plant viruses and their intimate integration within the plant cell requires an indirect approach for their control. This chapter will focus on the use of light manipulation to affect insects vision behavior in a way that interferes with their flight orientation, their primary landing on the crop, and the secondary dispersal within the crop. Manipulation of light signals simultaneously diminishes the insect immigration into the crop and reduces feeding contacts between the insect vector and the host plant, thus lowering significantly virus disease incidence.

2 The Insects Vision Apparatus

Insects perceive light through a single pair of compound eyes which facilitate a wide field of vision. The basic unit of the compound eyes is the ommatidium which rests on a basement membrane. The corneagen cells are located atop a long retinula formed by long neurons and secondary pigment cells. A crystalline cone lies within the corneagen cells. The dorsal surface of the ommatidium is covered with the corneal lens which is a specialized part of insect cuticle. Part of each retinula cell is a specialized area known as a rhabdomere. A nerve axon from each retinula cell projects through the basement membrane into the optic nerve. Ommatidia are functionally isolated because the retinula cells are surrounded by the secondary pigment cells (Diaz & Fereres, 2007).

Vision involves the transduction of light energy into a bioelectric signal within the nervous system. The first events in this process take place in the retinula cells. The fine structure of rhabdomeres consists of thousands of closely packed tubules (microvilli). The visual pigments occur mainly in these rhabdomeric microvilli. It has been suggested that the small diameter of each microvillus inhibits free rotation of visual pigments. This specific orientation may be the molecular basis of insects' sensitivity to polarized light. Photobiological processes in the insect eye occur in a narrow band of the electromagnetic spectrum between 300 and 700 nm. Visual pigments initiate vision by absorbing light in this spectral region. These pigments are a class of membrane-bound proteins known as opsins that are conjugated with a chromophore. Visual pigments whose chromophore is retinal are called rhodopsins. The visual pigments of all invertebrates, including insects, crustaceans, and squids, are all rhodopsins. According to which parameter of the light is being used or what information is extracted from the primary sensory data, vision is often divided into subcategories like polarization vision (Wehner & Labhart, 2006), color vision, depth perception, and motion vision (Borst, 2009). Polarization arises from the scattering of sunlight within the atmosphere enabling the insect to infer the location of the sun in the sky. The polarization plane is detected by an array of specialized photoreceptors (Heinze & Homberg, 2007). Many insects can discriminate between light wavelength (color) (Fukushi, 1990) its contrast and intensity. Motion signals are also part of vision cues that serve as a rich information source on the environment in which the insect is acting (Borst, 2009; Diaz & Fereres, 2007).

2.1 UV vision and insects behavior

In insects, the different visual pigments (opsins) are segregated into different subsets of cells that form the ommatidium. In the fruit fly Drosophila, seven genes encoding different opsins have been identified and sequenced (Hunt, Wilkie, Bowmaker, & Poopalasundaram, 2001). The ability of insects and mites (McEnrone & Dronka, 1966) to perceive light signals in the UV range (300–400 nm) is associated with the presence of specific photoreceptors within their compound eye. UV receptors of the greenhouse whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Westwood) as in other herbivorous insects are present in the dorsal eye region (Mellor, Bellingham, & Anderson, 1997; Vernon & Gillespie, 1990). Many insects have two rhodopsins, one with maximum absorption in ultraviolet wavelengths (365 nm) and one with maximum absorption in the green part of the spectrum (540 nm) (Borst, 2009; Matteson, Terry, Ascoli, & Gilbert, 1992). UV component of the light spectrum plays an important role in aspects of insect behavior, including orientation, navigation, feeding, and interaction between the sexes (Mazokhin-Porshnykov, 1969; Nguyen, Borgemeister, Max, & Poehling, 2009; Seliger, Lall, & Biggley, 1994). The involvement of UV rays in the flight behavior of some economically important insect pests has been studied by several workers (Coombe, 1982; Issacs, Willis, & Byrne, 1999; Kring, 1972; Matteson et al., 1992; Moericke, 1955; Mound, 1962; Vaishampayan, Kogan, Waldbauer, & Wooley, 1975; Vaishampayan, Waldbauer, & Kogan, 1975).

2.1.1 Effect of UV on insects dispersal and propagation

Whiteflies [Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius)] dispersal pattern under UV-absorbing films was examined using a release-recapture experiment. In “walk-in” tunnels covered with a UV-absorbing film and an ordinary film, a grid of yellow-sticky traps was established forming two concentric circles: an inner and an external. Under UV-absorbing films, significantly higher numbers of whiteflies were captured on the internal circle of traps than that on the external circle. The number of whiteflies that were captured on the external circle was much higher under regular covers, when compared with UV-absorbing covers, suggesting that filtration of UV light hindered the ability of whiteflies to disperse in a UV-deficient environment (Antignus, Nestel, Cohen, & Lapidot, 2001).

Following artificial infestation of pepper plants with the peach aphid [Myzus persicae (Sulzer)] in commercial tunnels, covered with a UV-absorbing film, aphid population growth and spread were significantly lower compared to tunnels covered with an ordinary film. In laboratory experiments, no differences in development time (larvae to adult) were observed when aphids were maintained in a UV-deficient environment. However, propagation was faster in cages covered with the regular film. The numbers of aphids was 1.5–2 times greater in cages or commercial tunnels covered with an ordinary film. In all experiments, the number of trapped winged aphids was significantly lower under UV-absorbing films. It was suggested that elimination of UV from the light spectrum reduces flight activity and dispersal of the alate aphids (Chyzik, Dobrinin, & Antignus, 2003).

Mazza, Izaguirre, Zavala, Scopel, and Ballaré (2002) reported that in choice situations Caliothrips phaseoli (Hood) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), favored areas with ambient UV-A (320–400 nm) radiation compared with areas where this part of the light spectrum was blocked. This type of behavior was explained by the relatively broad gap between the peak sensitivities of the photoreceptors that are responsible for sensing the UV range (365 nm) and the visible light (540 nm). It was assumed that under UV-deficient environment formed by the photoselective film, UV receptors are not stimulated by the ambient light, lacking the short wavelength (< 400 nm) and thus did not trigger the dispersal flight of thrips. Moreover, it was hypothesized that if only the 540-nm receptor is activated, thrips should be unable to discriminate colors but only light brightness...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.11.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Botanik | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Mikrobiologie / Immunologie | |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Land- / Forstwirtschaft / Fischerei | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-12-801264-1 / 0128012641 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-12-801264-2 / 9780128012642 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 18,4 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: PDF (Portable Document Format)

Mit einem festen Seitenlayout eignet sich die PDF besonders für Fachbücher mit Spalten, Tabellen und Abbildungen. Eine PDF kann auf fast allen Geräten angezeigt werden, ist aber für kleine Displays (Smartphone, eReader) nur eingeschränkt geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Größe: 23,6 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich