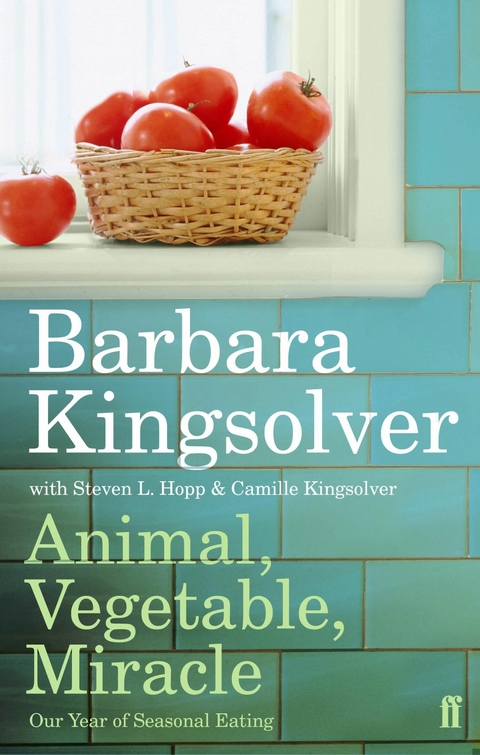

Animal, Vegetable, Miracle (eBook)

493 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-26566-4 (ISBN)

Barbara Kingsolver is the global prize-winning and bestselling author of novels including Unsheltered, Flight Behaviour, The Lacuna, The Poisonwood Bible and Demon Copperhead, as well as books of poetry, essays and creative non-fiction. Her work of narrative non-fiction is the influential bestseller Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life. Kingsolver's work has been translated into more than thirty languages and has earned literary awards and a devoted readership at home and abroad. She has won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the James Tait Black Prize for Fiction and is the first author to win the Women's Prize twice. Barbara lives with her family on a farm in southern Appalachia.

**DEMON COPPERHEAD - THE NEW BARBARA KINGSOLVER NOVEL - IS AVAILABLE NOW**THE MULTI-MILLION COPY SELLING AUTHOR"e;We wanted to live in a place that could feed us: where rain falls, crops grow, and drinking water bubbles up right out of the ground."e;Barbara Kingsolver opens her home to us, as she and her family attempt a year of eating only local food, much of it from their own garden. Inspired by the flavours and culinary arts of a local food culture, they explore many a farmers market and diversified organic farms at home and across the country. With characteristic warmth, Kingsolver shows us how to put food back at the centre of the political and family agenda. Animal, Vegetable, Miracle is part memoir, part journalistic investigation, and is full of original recipes that celebrate healthy eating, sustainability and the pleasures of good food.

A beautifully written plea for a return to authenticity in eating and food production.

Like the best meals, this is a family affair, with contributions from Kingsolver's husband and elder daughter. But it's younger daughter Lily who steals the show.

Warm and often hilarious.

Living off the land, and writing about it isn;t radical idea, but novelist Barbara Kigsolver gives old receipe a pleasurably folksy spin.

Kingsolver returns again and again to subjects such as food miles and the use of pesticides, and on these occasions her folksy humour turns into something much more polemical.

This is a rich rewarding book.

A question was nagging at our family now, and it was no longer, “When do we get there?” It was, “When do we start?”

We had come to the farmland to eat deliberately. We’d discussed for several years what that would actually mean. We only knew, somewhat abstractly, we were going to spend a year integrating our food choices with our family values, which include both “love your neighbor” and “try not to wreck every blooming thing on the planet while you’re here.”

We’d given ourselves nearly a year to settle in at the farm and address some priorities imposed by our hundred-year-old farmhouse, such as hundred-year-old plumbing. After some drastic remodeling, we’d moved into a house that still lacked some finishing touches, like doorknobs. And a back door. We nailed plywood over the opening so forest mammals wouldn’t wander into the kitchen.

Between home improvement projects, we did find time that first summer to grow a modest garden and can some tomatoes. In October the sober forests around us suddenly revealed their proclivity for cross-dressing. (Trees in Tucson didn’t just throw on scarlet and orange like this.) Then came the series of snowfalls that comprised the first inclement winter of the kids’ lives. One of our Tucson-bred girls was so dismayed by the cold, she adopted fleece-lined boots as orthodoxy, even indoors; the other was so thrilled with the concept of third grade canceled on account of snow, she kept her sled parked on the porch and developed rituals to enhance the odds.

With our local-food project still ahead of us, we spent time getting to know our farming neighbors and what they grew, but did our grocery shopping in fairly standard fashion. We relied as much as possible on the organic section and skipped the junk, but were getting our food mostly from elsewhere. At some point we meant to let go of the food pipeline. Our plan was to spend one whole year in genuine acquaintance with our food sources. If something in our diets came from outside our county or state, we’d need an extraordinary reason for buying it. (“I want it” is not extraordinary.) Others before us have publicized local food experiments: a Vancouver couple had announced the same intention just ahead of us, and were now reported to be eating dandelions. Our friend Gary Nabhan, in Tucson, had written an upbeat book on his local-food adventures, even after he poisoned himself with moldy mesquite flour and ate some roadkill. We were thinking of a different scenario. We hoped to establish that a normal-ish American family could be content on the fruits of our local foodshed.

It seemed unwise to start on January 1. February, when it came, looked just as bleak. When March arrived, the question started to nag: What are we waiting for? We needed an official start date to begin our 365-day experiment. It seemed sensible to start with the growing season, but what did that mean, exactly? When wild onions and creasy greens started to pop up along the roadsides? I drew the line at our family gleaning the ditches in the style of Les Misérables. Our neighborhood already saw us as objects of charity, I’m pretty sure. The cabin where we lived before moving into the farmhouse was extremely primitive quarters for a family of four. One summer when Lily was a toddler I’d gone to the hardware store to buy a big bucket in which to bathe her outdoors, because we didn’t have a bathtub or large sink. After the helpful hardware guys offered a few things that weren’t quite right, I made the mistake of explaining what I meant to use this bucket for. The store went quiet as all pitying eyes fell upon me, the Appalachian mother with the poster child on her hip.

So, no public creasy-greens picking. I decided we should define New Year’s Day of our local-food year with something cultivated and wonderful, the much-anticipated first real vegetable of the year. If the Europeans could make a big deal of its arrival, we could too: we were waiting for asparagus.

Two weeks before spring began on the calendar, I was outside with my boots in the mud and my parka pulled over my ears, scrutinizing the asparagus patch. Four summers earlier, when Steven and I decided this farm would someday be our permanent home, we’d worked to create the garden that would feed us, we hoped, into our old age. “Creation” is a large enough word for the sweaty, muscle-building project that took most of our summer and a lot of help from a friend with earth-moving equipment. Our challenge was the same one common to every farm in southern Appalachia: topography. Our farm lies inside a U-shaped mountain ridge. The forested hillsides slope down into a steep valley with a creek running down its center. This is what’s known as a “hollow” (or “holler,” if you’re from here). Out west they’d call it a canyon, but those have fewer trees and a lot more sunshine.

At the mouth of the hollow sits our tin-roofed farmhouse, some cleared fields and orchards, the old chestnut-sided barn and poultry house, and a gravel drive that runs down the hollow to the road. The cabin (now our guesthouse) lies up in the deep woods, as does the origin of our water supply—a spring-fed creek that runs past the house and along the lane, joining a bigger creek at the main road. We have more than a hundred acres here, virtually all of them too steep to cultivate. My grandfather used to say of farms like these, you could lop off the end of a row and let the potatoes roll into a basket. A nice image, but the truth is less fun. We tried cultivating the narrow stretch of nearly flat land along the creek, but the bottomland between our tall mountains gets direct sun only from late morning to mid-afternoon. It wasn’t enough to ripen a melon. For years we’d studied the lay of our land for a better plan.

Eventually we’d decided to set our garden into the south-facing mountainside, halfway up the slope behind the farmhouse. After clearing brambles we carved out two long terraces that hug the contour of the hill—less than a quarter of an acre altogether—constituting our only truly level property. Year by year we’ve enriched the soil with compost and cover crops, and planted the banks between terraces with blueberry bushes, peach and plum trees, hazelnuts, pecans, almonds, and raspberries. So we have come into the job of overseeing a hundred or so acres of woodlands that exhale oxygen and filter water for the common good, and about 4,000 square feet of tillable land that are meant to feed our family. And in one little corner of that, on a June day three years earlier, I had staked out my future in asparagus. It took a full day of trenching and planting to establish what I hope will be the last of the long trail of these beds I’ve left in the wake of my life.

Now, in March, as we waited for a sign to begin living off the land, this completely bare patch of ground was no burning bush of portent. (Though it was blackened with ash—we’d burned the dead stalks of last year’s plants to kill asparagus beetles.) Two months from this day, when it would be warm enough to plant corn and beans, the culinary happening of asparagus would be a memory, this patch a waist-high forest of feathery fronds. By summer’s end they’d resemble dwarf Christmas trees covered with tiny red balls. Then frost would knock them down. For about forty-eight weeks of the year, an asparagus plant is unrecognizable to anyone except an asparagus grower. Plenty of summer visitors to our garden have stood in the middle of the bed and asked, “What is this stuff, it’s beautiful!” We tell them it’s the asparagus patch, and they reply, “No, this, these feathery little trees?”

An asparagus spear only looks like its picture for one day of its life, usually in April, give or take a month as you travel from the Mason-Dixon line. The shoot emerges from the ground like a snub-nosed green snake headed for sunshine, rising so rapidly you can just about see it grow. If it doesn’t get its neck cut off at ground level as it emerges, it will keep growing. Each triangular scale on the spear rolls out into a branch, until the snake becomes a four-foot tree with delicate needles. Contrary to lore, fat spears are no more tender or mature than thin ones; each shoot begins life with its own particular girth. In the hours after emergence it lengthens, but does not appreciably fatten.

To step into another raging asparagus controversy, white spears are botanically no different from their green colleagues. White shoots have been deprived of sunlight by a heavy mulch pulled up over the plant’s crown. European growers go to this trouble for consumers who prefer the stalks before they’ve had their first blush of photosynthesis. Most Americans prefer the more developed taste of green. (Uncharacteristically, we’re opting for the better nutritional deal here also.) The same plant could produce white or green spears in alternate years, depending on how it is treated. If the spears are allowed to proceed beyond their first exploratory six inches, they’ll green out and grow tall and feathery like the houseplant known as asparagus fern,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.3.2010 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Grundkochbücher | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Gesunde Küche / Schlanke Küche | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Botanik | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz | |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Land- / Forstwirtschaft / Fischerei | |

| Schlagworte | booker prize winner • farmageddon • farming tales • Jamie Oliver • jonathan safran foer eating animals • robert macfarlane the old ways • Seasonal food |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-26566-9 / 0571265669 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-26566-4 / 9780571265664 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 771 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich