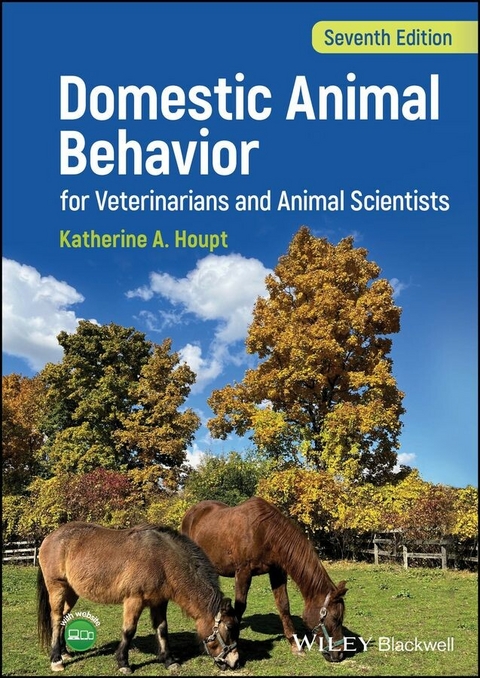

Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists (eBook)

496 Seiten

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-86111-9 (ISBN)

The Seventh Edition of Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists is a fully updated revision of this popular, classic text offering a thorough understanding of the normal behavior of domestic animals. Maintaining the foundation of earlier editions, chapters examine key behavior issues ranging from communication to social structure.

The Seventh Edition adds enhanced coverage of behavioral genetics, animal cognition, and learning, considering new knowledge and the very latest information throughout. Each chapter covers a wide variety of farm and companion animals, including dogs, cats, horses, pigs, sheep, cattle, and goats. Major additions are chicken and donkey behavior as well as the microbiome.

Each chapter covers a particular behavior subdivided by species. The information has been updated using information published in the past five years. To aid in reader comprehension and assist in self-learning, a companion website provides review questions and answers and the figures from the book in PowerPoint.

Sample topics covered in Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists include:

* Communication patterns, perception, vocalization, visual signals, social behavior, sleep and activity patterns, and detection of emotions in others

* Maternal behavior, pain- and fear-induced aggression, feeding habits, and behavioral problems (such as cribbing, offspring rejection and anxiety)

* Aggression and social structure, stereotypic behavior, free-ranging versus confined behavior, and maternal behavior (such as recognizing the young)

* Sexual behavior, development of behavior, and sleep behavior, including ultradian, circadian, annual, and other rhythms

* Ingestive behavior (food and water intake), hyperactivity and narcolepsy, and overall learning behavior

The role of genetics, the environment, and the microbiome in behavior The Seventh Edition of Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists is an essential reference for students of animal science and veterinary students, as well as qualified veterinarians and animal scientists seeking a more thorough understanding of the principles of animal behavior.

Katherine A. Houpt, VMD, PhD, DACVB, is Professor Emeritus of Behavioral Medicine at Cornell University's College of Veterinary Medicine in Ithaca, New York, USA.

Acknowledgements

About the companion website

1) Communication

2) Aggression and social structure

3) Biological Rhytrms, sleep and sterotypic behavior

4) Sexual Behavior

5) Maternal Behavior

6) Development

7) Learning

8) Ingestive Behavior: Food and Water intake

9) The Genome and the Microbiome

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Veterinärmedizin |

| Schlagworte | animal behavior • Animal Science & Zoology • Biowissenschaften • Haustiere • Life Sciences • Veterinärmedizin • Veterinary Medicine • Zoologie • Zoologie / Verhaltensforschung |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-86111-X / 111986111X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-86111-9 / 9781119861119 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,9 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich