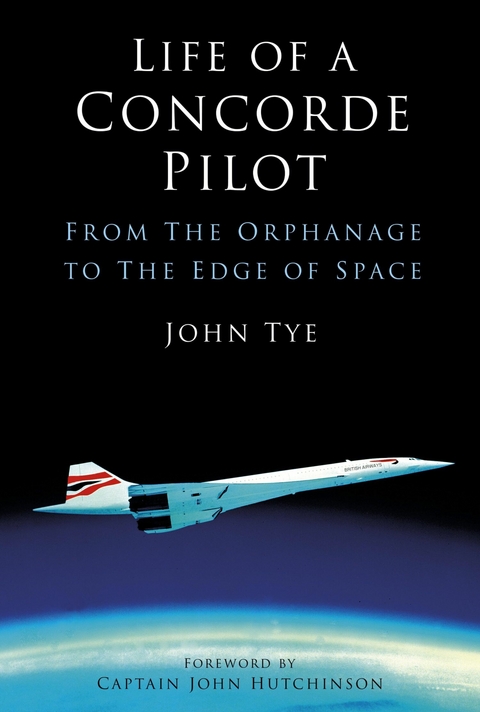

Life of a Concorde Pilot (eBook)

288 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-464-2 (ISBN)

John Tye joined BA in 1976 on the lowest clerical grade; 46 years later he retired as a former Concorde pilot and Senior Training captain, one of only 134 pilots who flew Concorde for BA. He also flew many other aircraft across his career, including Airbus, and has been very involved with children's charity, Dreamflight, for over 20 years.

John Tye's job at British Airways was supposed to be only temporary, a way for him to pass the summer before starting university. Instead, it would kickstart a forty-six-year career in aviation and take him all over the world. Told in an irrepressible and infectious style, Life of a Concorde Pilot is the story of how, despite a somewhat turbulent start to life in a Middlesex orphanage, John would go on to fly the world's only supersonic airliner. A true insight to the life of an airline pilot, with many amusing anecdotes along the way, it follows his ups and downs from his career on the ground at BA to flying with Dan Air and then back to BA, through to Covid and his reluctant retirement at the end of 2022. Full of the fascinating details only a pilot can give, this is a memorable journey to the edge of space and beyond.

PLANES, POP STARS AND A GLASS IN THE HEAD

Chris Tarrant was the breakfast show DJ on Capital Radio in the late 1990s and into the next century. He was a passenger on Concorde on a flight I piloted to New York in April 2000 and I had the opportunity to tell him how Capital Radio had played a part in me becoming a Concorde pilot.

Capital Radio Jobspot was a short advertising segment of the breakfast show each day in the mid-1970s. A jolly jingle heralded the promotion of the day’s vacancies and one in particular caught my ear over breakfast. Revenue accounts clerks (with eventual promotion to Concorde pilot) were being recruited by British Airways. Well OK, I made up the bit in brackets, but British Airways was a name that conjures up thoughts of prestige, pride and patriotism. I applied straight away, not that I had any desire to work in an accounts department, but it was at the airport and I’d had enough of clearing tables at Hampton Court Palace.

My A-level results came through and despite my somewhat lazy attitude to last-minute revision, I was awarded the grades I needed to secure my place at City University in London. I had a place to study Air Transport Engineering. It was to be a sandwich course, where you spent six months at university studying, followed by six months in industry gaining practical experience.

The industrial filling in the sandwich was, for successful applicants, to be provided by British Airways, but I didn’t make the grade. The university instead offered me the opportunity to embark on a full-time mechanical engineering course for three years.

I started at British Airways in revenue accounts on 9 August 1976.

It was meant to be a summer holiday job before going to university, but I stayed in the business for over forty-six years. It was a tough decision, but I didn’t take that university place.

The salary was £2,227 a year. The work was dull – sticking labels on bits of paper – but I was on the ninth floor of Technical Block C (TBC), on the airport perimeter in an open-plan office, with fantastic views across the airport. I was very well placed to continue my aircraft spotting and feel connected with all the goings-on at Heathrow.

Once employed within the airline it was always easier to move around and develop your career internally. Staff Vacancy Notices (SVNs) were posted on the board each Friday and it wasn’t long before I found myself moving on.

Just five months later, on 3 January 1977, I started work as, wait for it, a flight deck services assistant on a massive £3,320 a year. Based in the Queen’s Building, just two floors down from where Mum and Dad used to take me to watch the planes, I was part of a team compiling the Aircraft Library – all the manuals, maps and charts that the pilots needed for their voyages. I was fitted with a smart uniform and had to take a driving test to get my airside licence.

It was shift work and the 6 a.m. starts were a bit of a challenge. I was still technically a teenager after all. Sometimes you would spend the whole shift underground compiling the library and making up a big canvas bag of documents, but the best role was being out in the field. I’d be allocated my van for the day and be responsible for collecting the bag of documents and placing each manual or chart in the allocated stowage on the aircraft.

Here I was, driving a van and going on board aircraft of all different shapes and sizes, including Concorde. I was meeting pilots, had a walkie-talkie radio, and got to flirt with stewardesses. I couldn’t give that up to go to university.

I soon learned to be punctual meeting the inbound aircraft to secure my spot in the throng of other ground staff who were experienced at ‘raiding the larder’. The leftovers from first class in the 747 kitchens were highly sought after and the rear galley of Concorde after it pulled onto its parking spot, J2 at Terminal 3, was so crowded it was a wonder the aircraft didn’t tip on its tail.

Each time the intercontinental 707s, VC10s, 747s and Concorde returned home, all the manuals had to be removed and returned to the Aircraft Library for checking, updates and repairs. There were quite a few and they were heavy. It was good exercise lugging the heavy-duty green canvas bags up and down the stairs from the tarmac. There were performance manuals, navigation manuals, technical manuals, spare forms and, it seemed, the larger the aeroplane, the larger the books.

The first time I went on board a mighty 747 I was just blown away. Remember I’d only ever been in a Chipmunk RAF trainer before. This was something different altogether. Even once you were on board the aircraft itself, the flight deck was another flight of stairs up. A spiral staircase as well. That was tricky with several heavy canvas bags.

I had to sit down. Partly because I was out of breath after what seemed like climbing up to the third floor of a block of flats (which in fact it was), but mainly because when I entered the flight deck itself, I was just so overwhelmed. The two pilots’ seats were at the front. Obviously. The flight engineer’s seat was facing sideways towards an impressive panel covered in switches, dials and orange, green and red lights. I took time to look around to see if I could work out what any of it did. A few things made sense. The radios, for example, but most of what I studied was far beyond my level of comprehension. As I stretched across the co-pilot’s seat to access the manual stowage at floor level alongside it, it didn’t occur to me that in just over twelve years’ time I’d be climbing into that very seat wearing a different uniform to actually fly the beast. A lot of water had to go under various bridges first though.

My time in the Queen’s Building was fun and I was right in the midst of all the action, a vital part of the operation. I got to know a few of the pilots. The short-haul crews would fly around Europe and be found regularly in the crew report centre in the next room. The long-haul crews would have different procedures and head off to exotic, far-flung places around the globe, often away for up to three weeks.

Pete Rae and Chris Hawkes were a couple of Vanguard pilots I got to know quite well. The Vanguard was a large turboprop aircraft that had now been converted from its passenger-carrying role to cargo and been renamed the Merchantman.

Chris cleared it with his captain and invited me to go along for the ride one day in the late summer of 1977. We went across the Channel, over the Alps and into the industrial centre of Turin in Italy. As we crossed the Alps, much lower than modern jet aircraft, you could look down and see people walking in the snow. I had never seen such breathtaking views, my flying experience to date being limited to the aerobatics in the Chipmunk over Oxfordshire.

We thought we’d be stuck there for days. We couldn’t fly back with a cargo door warning light glowing red on the instrument panel. Chris and the captain had checked visually that the enormous hydraulically operated door on the side of the aircraft was closed, but the cockpit indications said otherwise. Something needed adjusting, possibly just a micro switch, but the red light had to be extinguished somehow.

I had to be careful not to fall out of the cargo door as we taxied out. The pilots had started the engines and had permission to proceed slowly along the taxiway as they operated the door. It was hinged at the top. They opened it a few inches with me standing on the bottom ledge and then slammed it shut with my weight contributing to the downwards momentum. That, combined with the airframe flexing and vibrating, fixed it. The door was shut and the light extinguished.

On the way back the captain vacated his seat and let me have a go at the controls. Here I was hand flying a Vanguard over the Alps in the clear blue skies. The flight controls were quite heavy compared to the Chipmunk, but I soon got the hang of it.

These guys got paid for doing this every day. I only had three A-levels though. The intelligence and skills required were surely beyond me? In hindsight, though, this was probably a life-changing experience, the first time I ever thought realistically about becoming a pilot.

Chris and Pete rented a house together with two stewardesses just around the corner from our family home in Sunbury. We frequented the same village pubs and I’d often be back at theirs after closing time. This pilot lifestyle seemed pretty good, both on and off the aeroplane. They seemed regular guys, not supermen. Maybe I did have the ability to become an airline pilot? Oh well, maybe one day.

Growing up in the 1970s was fun. It was a good decade to be a teenager. The music was great. You had to be there to appreciate that though. Slade, The Bay City Rollers, Sweet, T-Rex, Blackfoot Sue, Mungo Jerry and so on and so forth, if you liked glam rock. Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath, if your hair was long enough to like plain rock.

The clothes were great, too. You had to be there to get that as well though. I’m still hoping my flares will come back into fashion one day.

On the banks of the Thames and just a short walk (stagger) from home, the Magpie was a great pub in Lower Sunbury that Chris and Pete introduced me to. It became a regular haunt. My work in the Aircraft Library was on a shift basis, so I’d often pop in on the way home from work on my own. Closing time, officially 10.30 p.m. on weekdays, was a bit of a variable feast thanks to the relationship the landlord had with the local...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Luftfahrt / Raumfahrt | |

| Technik ► Fahrzeugbau / Schiffbau | |

| Technik ► Luft- / Raumfahrttechnik | |

| Schlagworte | 2000 concorde crash • 777s • Airbus • Air France Flight 4590 • Airline • Ba • base training • Boeing 777 • British Airways • celebrity passengers • Cockpit • Concord • Concorde • concorde pilot • Dan Air • disabled pilot • dreamflight • From The Orphanage to The Edge of Space • John Tye • pilot biography • pilot memoir • route training • spinal muscular atrophy • supersonic airliner |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-464-9 / 1803994649 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-464-2 / 9781803994642 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich