2

East King County

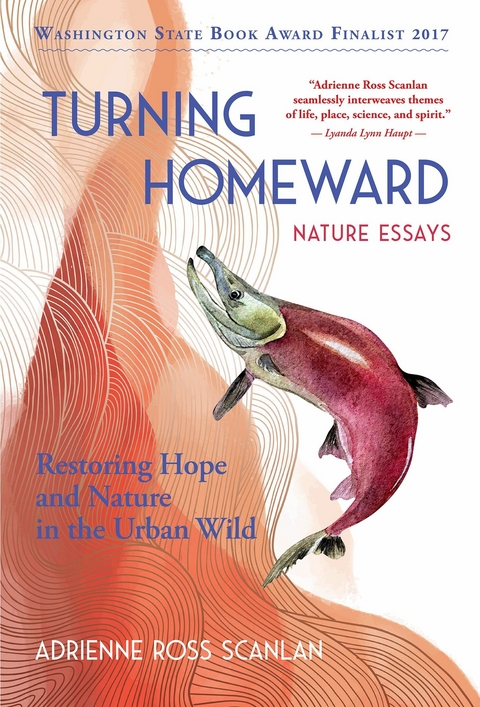

We were salvaging vine maple at this site, and cascara, Indian plum, ocean spray. Also any conifer we could find: western redcedar, Douglas fir, western hemlock. All are native flora often found along Pacific Northwest streams and waterways. By morning’s end, thousands of shrubs and seedlings, placed in burlap bags, would fill a rented moving truck. Thousands more would be left behind. The county organizes plant salvages when local forests are set to become housing developments, strip malls, or highways. The flora we were digging up would be replanted along streams, wetlands, and estuaries, many of which were salmon restoration sites.

Was I saving this forest? Or was I just another hand cutting it down?

This site was called Valley Green. Or perhaps it was The Gardens. It’s hard to tell one residential development from another. The nostalgic names belie the landscapes they create. A mud path from the forest had been widened to become a rain-slick asphalt road, twisting and curling through unmarked culs-de-sac. There were cleared plots of rock and grey dirt, white pipes, and neon-yellow earth-moving machines. Stuck in the dirt were white posts printed with black block letters that said “Storm Sewer Water.”

The model home was open for display. It was a beige house with a tan roof, four windows to each side, and a two-car garage. I tried to imagine what this land would look like with two hundred, three hundred, four hundred beige houses—all with clipped lawns—standing side by side. Weeks or months or years later, I might drive past The Gardens, Valley Green, or other suburban developments, with names like Meadowdale or Emerald Creek, and would never recognize the land where I had spent Saturday mornings filling burlap bags with big-leaf maple, thimbleberry, sword fern, salmonberry, snowberry, and more.

The county ecologist overseeing the several dozen volunteers was standing nearby. She was dressed for rain, of course. She wore boots and dirty jeans, and her white-streaked black hair was sheltered under a wide-brimmed khaki hat.

“How much is coming down?” I asked her.

We looked toward the forest. The woods were a labyrinth of salal, sword fern, Oregon grape, red huckleberry, and alder. Tight trillium buds were just rising from the dark, rain-soft earth. These were the few I had learned to notice and identify in this green blur of a forest. Growing beside them were so many more I had not yet come to know. It struck me: I’d lived in Seattle for nearly ten years, yet I was still so new to this region. And there I was learning to identify the flora by salvaging it.

I heard the trill of wrens. I heard the soft thud of shovels.

“All of it,” the ecologist said, shrugging. “All of it.”

“HOPE IS THE THING with feathers / that perches in the soul,” wrote Emily Dickinson. And in these woods, there were small hopes. Bumble bee queens, pregnant and waiting for spring, were somewhere hidden in the cracks of a nurse log or in the earth beneath a tangle of winter’s golden grass. A bird, perhaps twice as big as my thumb, flitted through the alder trees. I looked for field marks to identify it. I tried to remember the slides I’d seen at Seattle Audubon classes. Red-breasted nuthatch, most likely, I decided. A Pacific wren foraged under curling fronds of sword fern. That bird I knew. Chit, chit, chit, it called, so close I could see its pale eyebrows. Dark-eyed juncos with plumage looking like a monk’s brown cowl darted amid the roots and fallen leaves. At the edge of my sight, a hawk flew into an alder stand. A Cooper’s hawk, or perhaps a sharp-shinned hawk. There was a rustling in the fallen leaves, then silence. If woods like these kept coming down, would I ever have a chance to learn one accipiter from another?

When I was young, I wanted to save the world. I thought I could do that by organizing and boycotting and marching and leafleting and demonstrating against the big issues: nuclear proliferation; violence against women; so many other avoidable injustices of our time. I value that activism for what it changed in other people’s lives, and for what I learned from it; I trust it made a difference, however slight. I would do it again if necessary.

Now that I’m older, I still want to save the world. But time is costly. Passion more so. I no longer want to determine my actions and define my life by what I oppose. I want to act and live here in this world with what I love, simply and solely because I am coming to love it.

THROUGHOUT THE CENTURIES, sages from various schools of thought have talked of the anima mundi, the soul of the world. Annie Dillard, in For the Time Being, quotes Rabbi Menachem Nahum of Chernobyl, presumably the renowned eighteenth-century Hasidic rabbi, as saying “All being itself is derived from God and the presence of the Creator is in each created thing.” Dillard refers to this as the theological notion of pan-entheism (she added the hyphen to distinguish it from pantheism), a view she describes as God being seen as “immanent in everything” and where “everything is simultaneously in God, within God the transcendent. There is a divine, not just bushes.”

Is there a God? I don’t know. Is there evolution? Yes. Regardless of what caused life, are we separate souls lonely, disjointed, longing for salvation? I hope not. Are we a community, a shared life beyond our small knowledge? I hope so.

I FOUND A BUSH of barren limbs. Its branches ended in tight central buds surrounded by hornlike sprouts. Cascara. Its bitter silvery-grey bark was once used as a laxative. I dug the cascara out from under an alder stand and placed it in a moist burlap sack printed with the words Volcanbara Café—Coffee Peabody. Even in these woods, I’m not far from Seattle’s coffee-focused culture of gourmet microroasters and coffee shops on every street.

A conifer seedling was rooted under the shiny leaves of a salal. Its pencil-thin trunk was no higher than my knee. Short dark-green needles were scattered on its branches in a hectic, feathery pattern. I checked my field guide and then the notes I took during the volunteer training. Two thin lines on the underside of each needle were what helped me identify it—western hemlock.

Jim Pojar and Andy MacKinnon’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast, a classic field guide and my main reference for all matters botanical, describes how for the indigenous Northwest tribes the wood of western hemlock became hooks for catching halibut; festive bowls or everyday baskets; roasting spits; spear shafts; elderberry-picking hooks; and much more. Its branches made bedding, its pitch made liniment and poultices, and its bark was brewed with cascara and red alder to make a tea to stop internal bleeding.

Fragile roots, now shorn of earth, fluttered in the breeze. The seedling went into the burlap sack along with moist leaves and fragrant black earth.

I found what I thought was vine maple by its maroon bark and its pairs of buds on each twig tip. I checked my salvage list and training notes for the next plant to find, and started looking for Indian plum blossoms in the dull March rain, but I couldn’t find any. Instead, I found what I thought was red huckleberry, its thin green branches looking to me like an intricate notched fan. It was not on the salvage list. I left it behind.

TANGLE BILLIONS OF YEARS to make a forest. Add wind, rain, the pull of the moon, and the retreat of ice and snow. Throw in the price of lumber. Add bits of moss, feathers, and insect cocoons lining the nests of black-capped chickadees. Throw in the price of land. Add sun glinting on a bee’s wing, a spotted towhee under salal, my heartbeat, the broken pebbles scraping my shovel—all the mundane parts of life encompassing geological shifts, DNA, random chance, or whatever is the transformative force behind existence.

The forest at this salvage site had been logged at least once over the past century. Stumps slick with moss and rain were scattered between thick hemlock and alder covered with ebony-edged tufts of bone lichen. Logging surged in successive waves during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, tearing through ancient coastal forests of redwood, pine, spruce, hemlock, cedar, fir, and other native flora, which once stretched from Northern California through Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and on up to Prince William Sound in Alaska.

By the early 1990s, the remaining scattered, tattered forests were cut for their land more than their trees. Washington State lost some two million acres of forests between 1970 and the early 1990s, with nearly 10 percent replaced by urban, suburban, or agricultural uses. Between 1970 and 2000, King County’s population alone shot upward, as did its suburban and exurban developments. The county tried, but failed, to concentrate high-density growth within designated urban areas. Suburban and exurban lands increased, as did single-family housing. Wild lands and agricultural lands decreased.

The bits and pieces of forest we were salvaging would be replanted at restoration sites in parks and preserves, protected streams, wetlands, estuaries, and greenbelts. These disconnected habitats—that some call “biological islands”—can be particularly sensitive to habitat destruction and other drivers of extinction, such as invasive species that outcompete native species for food and shelter.

Was I saving this forest? Or was I just another hand cutting it down?

I never go back to these places after plant salvages. I want to believe I’m only here to help and...