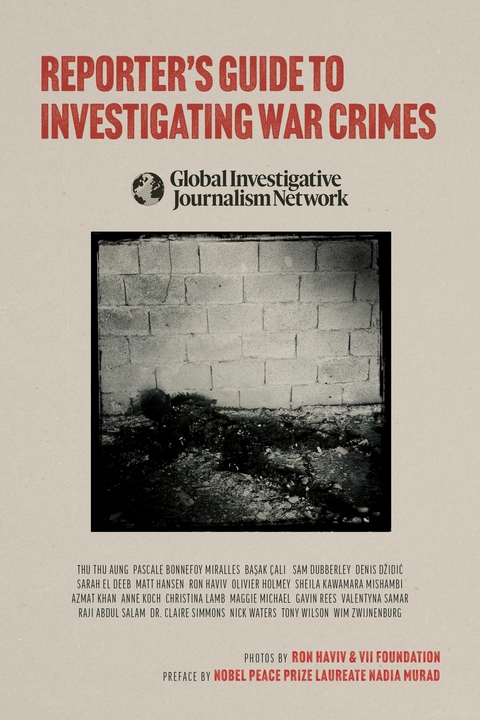

Reporter's Guide to Investigating War Crimes (eBook)

247 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-218-28148-9 (ISBN)

Nadia Murad, Nobel Peace Prize Winner "e;The work done by investigative journalists in war zones has the power to truly make a difference and this guide is a vital tool for reporters who choose to bring our stories to light."e;Eliot Higgins, Bellingcat Founder "e;An invaluable toolbox for truth-seekers, 'GIJN Reporter's Guide to Investigating War Crimes' bolsters the integrity of journalism in war torn regions. This comprehensive manual not only elucidates the complexities of war crimes, but also demystifies the codes governing them. With an unflinching spotlight on the grave responsibility borne by journalists, this guide bolsters the investigative process, empowering the narration of facts amidst chaos. Compulsory reading for journalists, human rights researchers, and legal authorities, this guide simplifies the intricacies involved in war-crime research, shining an undeterred light on the path to accountability for those who have transgressed the boundaries of international humanitarian laws."e;Marcela Turati, Mexican journalist "e;A wonderful piece of work by GIJN! I have been looking for a comprehensive resource like this for many years. It is the most extensive guide I've seen. It includes useful tips and resources, and the lived testimonies of experienced journalists. It's very useful not only for war correspondents reporting on cross-border warfare, but for those of us who are war correspondents within our own countries, covering atrocities committed by the police, narcos, soldiers, gangs, and traffickers. As well as a resource for journalists covering and investigating conflict, it also provides information, techniques, and tools for journalists and others who wish to use evidence to seek justice for victims and survivors, and to hold the perpetrators to account."e; Beauregard Tromp, Africa Editor at OCCRP"e;For more than a century journalists have rushed towards the sound of gunfire, intent on bearing witness to the horrors that war and conflict wreaks. The resulting correspondence has had mixed results, sometimes leaving survivors feeling even further violated and governments too often nonplussed. Drawn from among a pedigreed group of journalists who've covered wars and conflicts from Yemen to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Palestine to Ukraine, this guide is invaluable. Not only is it a guide to discerning between the terrible acts that constitute war and conflict but it also provides invaluable, practical notes on how to investigate potential war crimes, building irrefutable proof that can hold perpetrators to account and demand justice."e; Lindsey Hilsum, International Editor, Channel 4 News"e;As journalists, we sometimes find ourselves in situations where we need similar expertise and knowledge to war crimes investigators. This excellent and comprehensive guide provides not only advice on the sensitive interviewing of victims, but also information about the use of new technology to back up on-the-ground reporting. I would recommend it both to new and established reporters."e;Patrick Phongsathorn, Senior Advocacy Specialist, Fortify Rights"e;This guide is essential reading for journalists investigating potential war crimes. The laws of war can be confusing and bewildering, but this guide sets them out in a clear, concise, and easily comprehensible manner."e;

1

What is Legal in War?

by Claire Simmons | Photography by Ron Haviv, Maciek Nabrdalik

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum chronicles the Cambodian genocide. Located in Phnom Penh, the site is a former secondary school showing images of victims held at Security Prison 21 and killed by the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 until its fall in 1979. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

The horrors and destruction of war may lead one to believe that no laws apply in conflict, and that any attempt to regulate violence may seem pointless. Yet the very fact that we are horrified by certain acts more than others in such contexts indicates that we believe wars should have limits. This is a conviction that can be traced back centuries, although there may not always have been a common understanding of what these limits should be.

Our modern laws of war originated in the 19th century, as states agreed to sign the first international conventions to protect civilians and the sick and wounded in combat. Multiple international treaties have followed, including the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, which have become the most globally recognized texts regarding the laws of war. These four documents were drafted in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, which had provided a strong incentive for states to write down and commit to respect the commonly accepted rules and customs of war.

The concept of a “war crime” emerged alongside these treaties, as a term to describe the most serious violations of these laws of war. The international prosecution of such war crimes in courts became established with the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals following the Second World War, and in the 1990s, with international tribunals in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda set up by the United Nations.

But the laws of war can also matter outside of the courts. They can matter to individuals harmed by the violence, who may want recognition that they have been victims of injustice, even if they cannot go to court. They can also matter to soldiers involved in the conflicts, who want to know they are fighting for a just cause in a just manner.

Under international law today, the term “war crime” refers to specific, serious violations of international humanitarian law that lead to individual criminal responsibility. Not all violations of the laws in war are war crimes, however, and not all civilian deaths in war constitute war crimes, or even violations. Furthermore, the applicable laws of war and the enforcement mechanisms available (including international courts) depend on which treaties have been signed by which state.

Although the common understanding of the term “war crime” may have become divorced from the legal context, there is still value in understanding its precise legal meaning as well as the broader laws that apply in war to ensure credible reporting and possibly contribute to combating impunity for war crimes. It is also important to realize that some acts of war have serious consequences, including loss of life or serious injury to civilians, without being war crimes. Reporting on these acts while recognizing that no legal violation may have occurred can still be important to hold states politically accountable for the reduction of civilian harm in armed conflict.

This chapter lays out a basic overview of the laws that apply in armed conflict—and which acts may or may not be legal. It is not exhaustive, and further resources may be found in later parts of this guide. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an authoritative source for the interpretation of the applicable rules in armed conflict, and provides resources useful for journalists reporting in armed conflict.

A radio station broadcaster reads a list of names of missing children twice a day, provided by the ICRC, in the hopes of reuniting families, in Minova, Democratic Republic of the Congo, on Jan. 29, 2009. Numerous families have been connected this way. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Laws that Apply

Generally, the following laws apply in armed conflict:

- International humanitarian law (also known as the laws of war or laws of armed conflict), which regulates the actions of states and non-state armed groups that are parties to a conflict. This body of law deals mainly with state responsibility (or responsibility of armed groups) as opposed to individual responsibility.

- International criminal law, which regulates the international criminal responsibility of individual perpetrators of international crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes) in and outside of armed conflict. Although they are related, international criminal law and international humanitarian law are separate bodies of international law.

- International human rights law, which regulates the obligation of states (and in some cases, non-state actors) towards individuals within their territory and/or jurisdiction, although its application may sometimes differ in armed conflict.

- Domestic laws of the states.

- Other international laws and agreements entered into by the state, although their application may differ in armed conflict.

International humanitarian law only applies to situations that are determined to be armed conflicts based on specific legal criteria.

The body of law most relevant to acts of war is international humanitarian law, which only applies during armed conflict and regulates matters such as who may not be targeted (see principle of distinction below), the means and methods that may be used during the conduct of hostilities (such as which weapons are prohibited), and the treatment of those in the hands of the parties to the conflict, including persons in custody as well as persons no longer participating in hostilities.

Types of Armed Conflicts

International humanitarian law only applies to situations that are determined to be armed conflicts based on specific legal criteria.

Two different types of armed conflicts exist:

- International armed conflicts (often abbreviated as “IAC”) between states.

- Non-international armed conflicts (“NIAC”) between non-state armed groups and a state or between two or more non-state armed groups (sometimes referred to as civil wars, intra-state, or internal conflicts).

This distinction matters because the applicable legal framework differs, although the basic fundamental rules remain the same. The two are distinguished by the actors involved. Some conflicts involve both types of armed conflicts, which must be classified separately. Situations of armed occupation, in which a state occupies a part or whole territory of another state, are considered international armed conflicts, and specific rules governing these situations exist in treaty and custom. The existence of an armed conflict—and related applicability of international humanitarian law rules—may not always be clear from the outset (especially for NIACs), but some institutions map the possible existence of conflicts around the world.

Terminology: How ‘Armed Conflict’ Differs from ‘War’

International humanitarian law applies from the start of any “armed conflict.” This is a legal term, distinct but not mutually exclusive from other political terms such as “war.” The outbreak of a “war” may be used in a political sense (e.g., a “civil war,” the “war on drugs,” or the “war on terrorism”) but may or may not include an armed conflict and, therefore, determine whether international humanitarian law applies or not. Legal criteria exist to determine whether or not an armed conflict exists:

- An international armed conflict is triggered by the use of armed force between sovereign states (in theory, even a single shot across borders could meet the definition).

- The existence of a non-international armed conflict depends on the protraction and intensity of violence and the organizational structure of the armed group(s) involved.

Not All Laws Apply to All States

Under international law, states are only bound by the laws to which they have agreed, usually through ratification of treaties (signing and implementing in domestic law) or through customary international law. The UN Treaty Database, the ICRC IHL Database, and other online resources contain lists and information on which states have ratified which treaties.

Parties to an armed conflict are bound by:

- Treaty law

- Which is only binding on the states that have ratified the treaty in question.

- International humanitarian law treaties, such as the Four Geneva Conventions of 1949, which have been ratified by every recognized state (but which lack detailed provisions regarding certain rules, including those applicable to non-international armed conflicts) and their...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.2.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-218-28148-9 / 9798218281489 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 7,8 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich