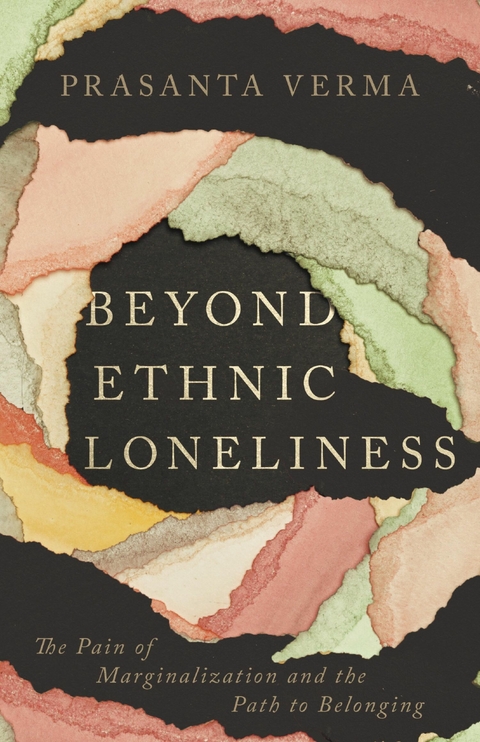

Beyond Ethnic Loneliness (eBook)

224 Seiten

IVP (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0742-6 (ISBN)

Prasanta Verma (MBA, MPH) was born under an Asian sun, raised in the Appalachian foothills in the South, and now resides in the Upper Midwest. Her essays and poetry have been published in Sojourners, Propel Women, (in)courage, Inheritance Magazine, the Indianapolis Review, Barren Magazine, and the Mudroom blog. She served as a speech and debate coach for over ten years. When she's not writing, speaking, or working, she's drinking chai, walking, or reading. Prasanta lives with her family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Prasanta Verma (MBA, MPH) was born under an Asian sun, raised in the Appalachian foothills in the South, and now resides in the Upper Midwest. Her essays and poetry have been published in Sojourners, Propel Women, (in)courage, Inheritance Magazine, the Indianapolis Review, Barren Magazine, and the Mudroom blog. She served as a speech and debate coach for over ten years. When she's not writing, speaking, or working, she's drinking chai, walking, or reading. Prasanta lives with her family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Introduction

A COUNTRY WITH NO NAME

I long, as does every human being, to be

at home wherever I find myself.

Go back to Indiana, or wherever it is you came from!” she hissed.1 I cannot recall what preceded her comment, nor what precipitated her hatred. She didn’t like me, and for no apparent reason except one: my skin color.

We were on the softball field for recess. In the outfield, well out of the teacher’s earshot, no one else could hear our conversation. It was a typically hot, sunny southern day and I could feel the red clay beneath my feet burning like hot coals. My classmate turned toward me, her eyes seething with hatred and bitterness.

Sound travels faster in humid air, stinging the ears more quickly than normal. I said nothing in response but knew what she meant. Naming a state—Indiana—instead of the country—India—made her meaning undeniably clear. Or was that simply how little third graders in rural Alabama really knew? My family was, as far as we were aware, the only Indian family within a forty-five-minute radius, and my classmate had never met (or presumably seen) anyone else from the far-off land of “Indiana.”

At that moment, I didn’t cry. I didn’t tell my parents what my classmate said. In fact, I didn’t tell anyone. I felt pushed to the side and felt the loneliness of being different. It wasn’t until years later that I began to process and speak of situations like this, times when I felt alone in my experience of being an immigrant or someone who looked different from others.

But where was she telling me to return to? I was puzzled. My family had recently moved from South Dakota, so that was the only place that made logical sense in my mind. It did not occur to me to go back anywhere else. I was born in India, so perhaps she thought we had recently clambered off our own canoes from the Gulf Coast and walked north. She didn’t know I was one year old when my parents immigrated, that this was the only country I had ever known.

But in my head, I’ve been going back ever since, trying to find that place called home.

I have never forgotten her words.

My experience that day on the playground opened my eyes, as my classmate clearly told me who I was not. Her words reminded me of what she and others saw when they looked at me. I looked at me and saw “American.” Others looked at me and saw “foreigner,” “Indian,” or “Asian.” At that age, it was not obvious to me that I was different from anyone else, because I thought and spoke like an “American.” But I didn’t look like one to her, which is to say, white. I lived with that tension for years, struggling to figure out where I belonged, seeking to find terms to explain my identity. What did it mean to be Indian? American? Asian? Brown? What was I? Where did I fit in?

To make matters more confusing, filling out forms in later years that asked for my race was perplexing. I didn’t belong in any category on the list. The closest group was “Asian/Pacific Islander,” but that didn’t fit because Asia is quite diverse, yet the form only had one box for us all. If a person who didn’t know me simply looked at the “Asian/Pacific Islander” box checked on my form, they wouldn’t know which country I’m from.

Asians are lumped into one category, one blob, with no distinction made for our unique identities. We don’t have a defined country on these forms. We are one mass tied together because of geography. Asia, comprising forty-eight countries, is four times bigger than the United States, and is the most populous continent in the world, with diverse people groups. Yet, Asians are treated as an aggregate. In fact, when I was young, I thought Asian referred to someone from China. I didn’t realize the term also applied to me!

As a teenager and young adult, I used to be angry at God for my skin color and for putting me in the middle of two cultures. If God wanted me to be Indian, why had my parents left India? If God wanted me to be American, why did I look Indian? Why had God made my life complicated in this way? Everyone had different expectations of me. Americans looked at my external appearance and expected me to be Indian, not knowing if I spoke English. Strangers stayed distant and distrustful because of my skin color, or because of my ethnic name. Indians expected me to be Indian, sometimes speaking to me in Hindi or some other language. Yet I do not speak these languages. I only understand a little bit of my parents’ mother tongue, Punjabi. Sometimes I wanted to shout to my peers and the world, “I’m American!”

I went through phases when I rebelled against anything Indian, to the point of saying, “I’m not Indian!” Friends and family would look at me in surprise and amusement because that’s not what my skin color conveyed to them. I often felt like I was living in a land of in-between, in a country with no name, a liminal space, not fitting in anywhere.

Other than my own family, I didn’t know anyone like myself: of Indian descent but raised in the United States. Even today, most of the Indians I know grew up in India and came to the United States for college or a job. Living in a small southern town, I did not grow up close to others like me. Plus, most Indians are Hindus, which placed me further in that land of in-between, for I had broken with my Hindu background and my parents’ religion and began attending church as a child and teenager.

In my twenties, due to job prospects, I moved from Alabama to Milwaukee—a city that would later be designated “the most segregated city in America.” People sometimes ask me, “Wasn’t it really racist in the South?” If only racism could be so easily contained. People are often shocked, and some even express disbelief, when I tell them of my experiences with racism in Milwaukee: the time when I walked into a store and was ignored while salespeople approached other customers; being given the finger while simply driving; the clerk at the exit door at the Costco who spends extra time looking over my receipt while glossing over others’ (I’ve counted and watched, multiple times). Or there have been times when I would share about my experiences and others would launch into an explanation of the hierarchical structures between Italian, Polish, German, and other European groups that existed in Milwaukee, and the discrimination against Italians. When I had a story of oppression to tell, why were white people so quick to draw parallels with me rather than the oppressor?

People of color have consistently been marginalized in a white-centric society. We have felt invisible and lonely. We have been devalued, attacked, beaten, shot, lynched, enslaved, exiled, killed. Asians have been marginalized and made invisible; Black people have been devalued, enslaved, and murdered; Indigenous people have been erased and oppressed; Latin Americans have been discriminated against and publicly marginalized. This is by no means an exhaustive list of affected groups, and these adjectives are incomplete and inadequate to describe all the trauma, pain, and centuries of oppression. But with increasing loneliness, alienation, disconnection, and polarization not only in the United States but also globally, finding a sense of belonging is an urgent task for the person of color today.

Living in this in-between place lends itself to a peculiar kind of loneliness: specifically, ethnic and racial loneliness. It has taken years to untangle and unpack internal dialogues and assimilation strategies I developed, years of reckoning and soul-searching to reach a place of peace and rest regarding my identity.

There are different kinds of loneliness. Loneliness can be situational, emotional, social, physical, geographic, or spiritual. In this book, I’ll focus on racial and ethnic loneliness. This book is about recognizing, living with, and shedding light on this kind of loneliness, and finding hope within it, in spite of it, and beyond it. I’ll discuss disbelonging, marginalization, isolation, othering; the longing to belong, to be known, to be seen; and strategies for alleviating ethnic loneliness. Together we’ll find out that belonging is multitiered, as we discuss belonging to ourselves, to others, to community, and to God, and it is applicable for those with a faith background or those without. In fact, we might even learn that loneliness is often the status quo rather than the exception, and our places of exile are places we find hope, and where we can find belonging even in spite of living in exile.

I write to honor my parents’ experience, other immigrants’ experiences, and the experience of people of color. I also write from my own perspective. I cannot pretend to understand the many and varied experiences of all people of color. Yet there are aspects we share, and I hope to shed light on how it feels to be in this liminal space, to remind us that we are not alone. By the end, I hope to help us more deeply understand ethnic and racial loneliness, what can be done to help assuage this ache of loneliness, and how to find a place of belonging.

There is hope for the person of color who feels marginalized and like they are living in in-between spaces. A path toward healing and belonging is possible as we understand and claim our identity. We’ll find the answers to that perennial question “So, what are you?” and answers for when we’re told to go back to our own individual Indianas, either directly or indirectly. So, let’s travel...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Asian immigrant • Cultural Alienation • Cultural Isolation • ethnic loneliness • Immigrant community • Immigrant Experience • loneliness • marginalization • minority experience • People of Color • racial trauma • Racism • south Asian immigrant |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0742-8 / 1514007428 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0742-6 / 9781514007426 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich