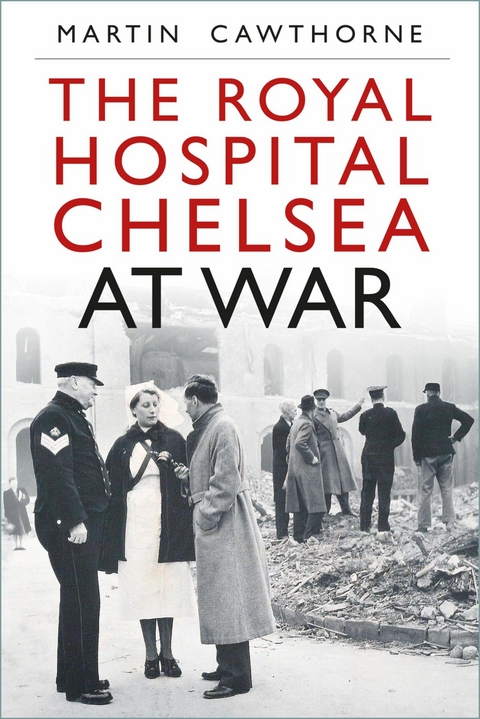

The Royal Hospital Chelsea at War (eBook)

344 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-600-4 (ISBN)

MARTIN CAWTHORNE spent a career in finance before he began volunteering at the Royal Hospital. He worked on a project to digitise part of the institution's archive collection while undertaking a Master's degree in Historical Studies at the University of Oxford, for which he researched the Hospital's wartime history. Martin is now recognised as the expert on the institution's wartime story and works with the Royal Hospital Chelsea on a number of heritage and outreach projects.

1

Pre-War Civil Defence Planning

‘The Bomber will always get through.’1

The First World War resulted in over 10 million deaths and was widely believed to have been a war to end all wars.2 However, not everybody accepted the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, and in 1922 a demobilised German soldier called Adolf Hitler railed against his country’s defeat, ‘It cannot be that two million Germans should have fallen in vain […] No, we do not pardon, we demand – vengeance!’3 With Hitler and the Nazi Party’s subsequent rise to power, war clouds were once again forming over Europe and as calls for rearmament grew louder, attention in Britain turned to preparations on the Home Front.

Several towns and cities, particularly London, had faced aerial bombing in the First World War.4 The Royal Hospital Chelsea sustained damage and casualties during a raid in 1918 when a 1,000kg bomb dropped by a Staaken ‘Giant’ bomber destroyed the North-East Wing, killing Captain of Invalids Ernest Ludlow MC and his family.5 This was the largest bomb dropped on London during the First World War.6

Conventional thinking in the interwar years strongly favoured the view that the ‘bomber would always get through’ as articulated by Stanley Baldwin in a debate in the House of Commons on 10 November 1932, ‘I think it is well also for the man in the street to realize that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed, whatever people may tell him. The bomber will always get through.’7

This widely held view led to a debate around how best to protect the civilian population from the anticipated aerial Armageddon. From 1923, Air Raid Precautions (ARP) in Britain were the responsibility of the Committee of Imperial Defence, an advisory body founded by the government in 1904.8 Initially, the ‘committee worked on the development of wartime measures, such as Auxiliary Fire brigades, barrage balloons and inner-city trenches’.9 However, cost considerations were a major factor in determining the level of pre-war Civil Defence expenditure, particularly given the crippling impact of the Great Depression following the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

In the mid-1930s, central government sought to include local government in the Civil Defence debate and the Home Office published a circular in 1935 ‘inviting suggestions from local authorities for their wartime measures’.10 It is from this point that evacuation strategies can be traced as an integral part of defence planning on the Home Front. The debate moved from a focus on protecting civilians in situ to instead considering the merits of moving vulnerable groups from areas of potential danger to places of relative safety.

In 1938, a government committee set up under the chairmanship of Sir John Anderson to consider Civil Defence options reported its findings.11 Detailed consideration was given to events surrounding the Japanese invasion of Chinese Manchuria and attacks against civilian targets in the Spanish Civil War. The well-publicised bombing of the city of Guernica was well known among both military and civilian society. The Anderson Report presented a compelling argument in favour of evacuation:

Apart from the danger to life and limb, there are obviously strong objections on humanitarian grounds to the retention, in areas which are likely to be the object of deliberate attack of persons whose presence is not absolutely essential. It is impossible fully to envisage the horrors of intensive air attack by the forces of a major European power on a densely populated city; but events in Spain and China have at least given some indication of what might befall. No one would willingly expose children, the aged or infirm, or anyone whose presence could be dispensed with to the nervous strain entailed.12

The Anderson Report divided the country into three zones – evacuation, neutral and reception – with the intention that local authorities in evacuation zones would liaise with those in reception areas to facilitate and co-ordinate the movement of vulnerable groups to a place of comparative safety. Leadership at the national level was to come from the Home Office, with Anderson identifying ‘the Home Secretary responsible for giving general directions regarding schemes for the evacuation of the civilian population’.13 At the detailed operational level, the task of administering the evacuation proposals was delegated to the Ministry of Health. However, it quickly became apparent that evacuation planning would be fraught with difficulties. At the outset of the scheme there was little agreement as to which areas of the country should fall into each zone:

Over 200 local authorities in England and Wales graded as reception asked to be ranked as neutral, and another sixty wanted to be scheduled for evacuation. It is significant of the temper of the country at that time that no authority zoned as evacuable disputed the Ministry of Health’s decision, and no authority asked to be a reception area.14

Although it was envisaged that evacuation would be voluntary, the report nevertheless established officially designated ‘priority groups’ eligible for publicly funded support. These were identified, in the sometimes inelegant language of the day, as including:

1. Schoolchildren, removed as school units under the charge of their teachers.

2. Younger children, accompanied by their mothers or by some other responsible person.

3. Expectant mothers.

4. Adult blind persons and cripples where removal was feasible.15

Local authorities would co-ordinate their plans to best meet the specific requirements of each of these priority groups, with problems that were identified in advance by the Anderson Committee to be solved through local co-operation, co-ordinated at a national level.

It was recognised at the outset that the scale of potential evacuation envisaged was inevitably going to create significant logistical challenges which would need to be overcome. Nevertheless, government departments would rise to the challenges encountered and so it was expected that, for example, the Ministry of Transport would ensure ‘transport facilities can be provided to meet the needs of any orderly scheme of evacuation’.16

Finding suitable accommodation for all the anticipated evacuees was, however, considered to be an altogether more difficult problem. It was felt that there was a ‘definite limit on the extent to which billets can be found’.17 Consequently, it was agreed that it would ‘be necessary to give the authorities the power in time of war to requisition accommodation for the billeting of evacuees’.18 The task of drawing up lists of suitable accommodation which could be requisitioned if necessary fell to the Office of Works.

Originally established in 1378, under the leadership of a Surveyor of the King’s Works, the Office of Works was responsible for the construction and maintenance of royal castles and palaces. In 1682, it was the Office of Works, under the guidance of Christopher Wren, which had built the Royal Hospital Chelsea, and in the 1930s it still retained responsibility for the maintenance of the Hospital’s buildings and grounds.

Although a quasi-independent entity within Whitehall, the Office of Works reported to the Home Secretary and as such was notionally under the control of the Home Office.19 With extensive in-house expertise in property management, it was to play an important role in Civil Defence and as evacuation planning progressed, the role of the Office of Works was quickly formalised:

At a meeting of the Imperial Defence Committee on the 15th April 1937, it was decided that secret surveys should be undertaken of buildings that could be utilised, and the information fed into a central requisitioning register. This was made the responsibility of the Office of Works.20

Officials subsequently toured the country compiling lists of properties which could be requisitioned should the need arise. Internal discussions were regularly held about which buildings could be used for meeting the various requirements the Office of Works had been asked to consider.

An important factor which significantly influenced evacuation planning was the widely held view about the likelihood of enemy bombers inevitably ‘getting through’. It was anticipated that the unavoidable consequence of these attacks on heavily populated civilian centres, regardless of the prior evacuation of vulnerable groups, would undoubtedly result in considerable casualties among the remaining inhabitants of targeted areas. The Imperial Defence Committee estimated that should the United Kingdom face a sixty-day bombing campaign, this would most likely result in as many as 600,000 dead and 1.2 million wounded.21 These considerations inevitably played a major part in the deliberations among officials at the Office of Works as they compiled the requisition register, and resulted in numerous buildings being identified as potential candidates for emergency casualty clearing hospitals for the anticipated flood of air-raid victims. This focus on air-raid casualties would have important implications for the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

Although in theory there was to be no distinction between the priority groups officially identified in the Anderson Report, in practice, this was not the case. The committee ‘devoted special attention to the manner in which...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 37 black and white illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | chelsea hospital • chelsea pensioners • civil defence • london blitz • long ward • Royal Hospital • The Blitz • world war one veterans • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-600-5 / 1803996005 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-600-4 / 9781803996004 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich