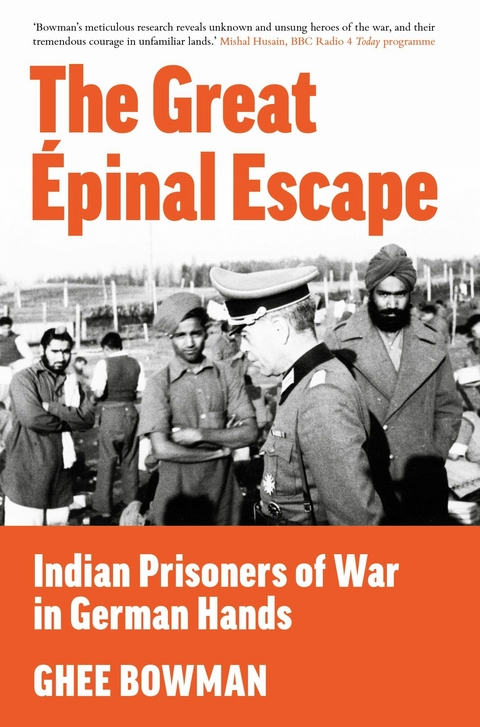

The Great Épinal Escape (eBook)

272 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-501-4 (ISBN)

GHEE BOWMAN has a PhD from the University of Exeter. His first book, The Indian Contingent, led him to discover the little-known events at Épinal. He is an experienced international researcher and seasoned public speaker, with a passion for social justice. As a historical consultant (advising on a range of projects including the BBC's The Pursuit of Love), he has established himself as an expert on the Indian Army and the Second World.

1

The Indian Army in Africa and Europe

Lo! I have flung to the East and West

Priceless treasures torn from my breast,

And yielded the sons of my stricken womb

To the drum-beats of duty, the sabres of doom.1

Barkat Ali came from Punjab and Harkabahadur Rai from Nepal, two of the traditional British recruiting grounds. British recruitment was based on the so-called Martial Race Theory, the widely held belief that some people were inherently good at fighting – it was ‘in their blood’.2 Europe in the 1930s and 1940s witnessed the historical high point of racism. Nazism was an attempt to make racism the dominant world order. It failed.

But racism was not restricted to Germany. It was built into the British imperial system and built into the Indian Army as part of that imperial system. Young men from Punjab – Sikhs and Muslims – were praised as warriors and targeted for the army. Meanwhile, young men from Bengal were seen as weak, effeminate ‘babus’, who were good only for clerical work and could never fight. Pressure on numbers throughout the Second World War would see the abandonment of that prejudice, from necessity rather than principle, and the 2.5 million men who served came from across the subcontinent, as did the 15,000 who became prisoners of the Germans.

This was an army in transition, from a country in transition. Indian opinions about the war were divided – talking of ‘Undivided India’ at the time is an illusion. The politicians, the people, even the type of government varied enormously across India. While Sikandar Hayat Khan’s Unionist Party in Punjab was all-out in favour of the British and Jinnah’s Muslim League took a broadly pro-British stance, the Congress Party took an altogether different line.

With the idea of independence firmly in their sights, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru – although both anti-fascist in outlook – were not prepared to support the British war effort unless and until independence was secured. For Churchill and the British Viceroy, everything else was secondary to winning the war. For Gandhi and Nehru, it was the reverse: independence came first and ‘All other issues are subordinate’.3

Yet another view was held by many, led by Subhas Chandra Bose, previously President of the Congress Party. Bose – known as ‘Netaji’, or respected leader – saw Britain as the enemy, and with the irrefutable logic of ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’, sought to find ways to enlist Indians in armies that would fight against Britain and on the side of the Germans and Japanese.

Indian soldiers – even fellow Bengalis – had mixed feelings about Bose. A young army medical officer called Dutt, although a nationalist, ‘was conflicted … he didn’t agree that Indians should join the Axis … you don’t consort with evil to get something done … he decided he would fight on the side of the right’.4

The men in Épinal and the other European prisoner-of-war (POW) camps came from across this spectrum, sometimes with loyalties that changed more than once.

Some of the future recruits to Bose’s forces were already officers in the Indian Army, men like Mohan Singh of the 1/14th Punjabs, with five years’ experience under his belt. He wrote later that soldiers of free nations ‘fought because freedom of their country is their first duty, whereas the Indian soldiers fought because they were paid for it by our alien rulers’.5

This view of the Indian Army as being essentially composed of mercenaries is at least partly true. The motivations that brought young Indians to the recruiting officer were of course a mixture, as are those of any soldier. Unlike in Britain and the White Dominions, there was no conscription in imperial India, so historians sometimes talk of the 2.5 million men as ‘the largest volunteer army ever’.6 The word ‘volunteer’ carries overtones of volition or choice, but many sepoys had little choice. They joined up because it was expected of them; because their forefathers and cousins had joined; because it was tradition. They could look at the old soldiers back in the village with their medal ribbons and their strips of land and know that this was a way to secure the future prosperity of their family, as well as the immediate fullness of their belly. Every Indian soldier sent back money to his family, and many villages in Punjab and Nepal owed most of their income to these remittances. An anonymous Épinal escapee reflected on his experience of soldiering as a career move, years later in Switzerland:

All Indian soldiers are volunteers. I signed up when I was 16 years old … In peacetime there were many [of us], the English did not make us aware that there could be war. Englishmen, also Indian officers, led our training, which was not very strict. Once a night march lasted until 2 a.m., then we were brought in on trucks to the barracks. We shot for a week a year with our guns and machine guns. We also got trained for transport vehicles. We had vacation for 3 whole months a year, plus 10 days at Christmas. Once there was a 3-day field service exercise, but there was no live shooting.7

That sentence, ‘the English did not make us aware that there could be war’, is significant. Despite the evidence of history, many of these young men had no idea that they would be transported in ships around the globe, be shot at by other uniformed men and spend years behind barbed wire.

Some of the Indian Army prisoners were officers, and some of those were Indians. By 1939, the Indian Army was deep into a process of ‘Indianisation’: the gradual replacement of the old white British officer class with indigenous Indians, a process that was massively accelerated over the following ten years of war and independence. Many of the senior-most officers of the post-Partition Indian and Pakistani armies had been trained by the British in the 1920s and 1930s; men like Kodandera Madappa Cariappa, the first Indian Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, and Muhammad Akbar Khan – with the Pakistan Army No. PA1 – were among the very first Indians to receive a King’s Commission, training together at Indore in 1919.8 There were also many Indian medical officers, even one in the British Army itself, and the medical needs of many POWs – Indians and others – were met by doctors from India.9

As well as the officer ranks that would have been familiar in any army, the Indian Army featured some strange ranks that would prove difficult for the Germans to delineate and would lead to tension in POW camps. These were the Viceroy’s commissioned officers, or VCOs – jemadars, subedars and risaldars – situated between non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and King’s commissioned officers (KCOs). VCOs were men who had come up through the ranks, often after many years of service, and commanded a platoon or troop. Before the Indianisation process, this was as high as an Indian could get in the Indian Army.

Besides reducing the need for white British officers in a regiment, their job was in some ways that of cultural and linguistic interpretation – helping the men to understand the British and the officers to understand the Indians. The Germans were confused over the VCOs’ status and requested clarification from the British via the Red Cross.10 The British preference was that they should be treated as equivalent to officers and housed in the same camps, and the Germans duly went along with this.

An additional complication was the status of Indian warrant officers, who were accustomed to being treated the same as VCOs in India.11 In fact, they were transferred around from officers’ camp to privates’ camp, and a group of eleven of them wrote a letter of complaint to the Swiss authorities about this upgrading and downgrading, eloquently pointing out the advantages of the officers’ camp.12

One officer POW was Santi Pada Dutt, from Dhaka in East Bengal, who had been a newly trained doctor aged 25 when the war started. His daughter described his first meeting with a Briton called Masters – the Adjutant of the 4th Gurkha Rifles, his new regiment:

My father walked into his office. Masters greeted him.

‘What’s your name?’

He gave him his last name.

‘What’s your Christian name?’

My father stopped and said, ‘I don’t have a Christian name.’

‘Don’t waste my time!’

‘I’m not a Christian, I’m a Hindu. I don’t have a Christian name! I do have a middle name and a first name.’

Masters had a long history with India – to my surprise something as basic as this hadn’t occurred to him.

Masters then spoke to Colonel Wheland and said, ‘I think this chap is a good egg – he will do well for our medical officer’.13

Dutt was captured at the Battle of the Cauldron in June 1942 and imprisoned in Italy. He was later awarded the Military Cross for his heroism in continuing to treat wounded Gurkhas while being bombarded by German artillery and then overrun.14 Later, Dr Dutt said of his decision to remain with the troops, ‘How could I leave them? They were my boys.’15

Among the very first Indian ‘boys’ to become prisoners of the Germans were those who were not soldiers, nor even...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | 2nd World War • Epinal and the Indian Prisoners of War • Etobon • Gestapo • great escape • Gurkhas • Hindus • Indian Army • Indian military history • india world war • largest escape • mighty eightt • Milag Nord Great Escape • moselle river • Muslims • Nazi Germany • Oflag • Pakistan Army • pow escape • POWs • Prisoners of war • Second World War • Sikhs • Stalag • Vosges • World War 2 • World War II • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-501-7 / 1803995017 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-501-4 / 9781803995014 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich