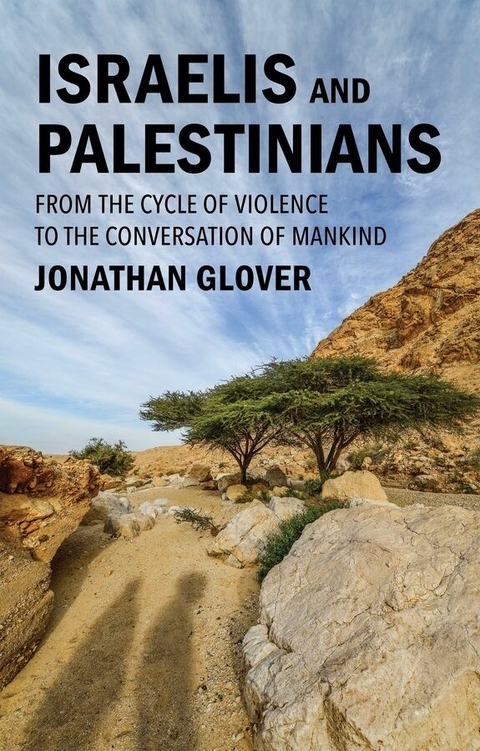

Israelis and Palestinians (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-5095-5979-4 (ISBN)

Can Israelis and Palestinians end their long conflict? The shocking violence of current events undermines hope, as does the long history of peace deals sabotaged by extremists on both sides. In this compelling and timely book, the eminent moral philosopher Jonathan Glover argues that one vital step towards progress is to better understand the disturbing psychology of the cycle of violence.

Glover explores the psychological flaws that entrap both sides: the urge to respond to wounds or humiliation with backlash; political or religious beliefs held with a rigidity that excludes compromise; and people's identity being shaped by the conflict in ways that make it harder to imagine or even desire alternatives. Drawing on the history of comparable conflicts that eased over time, Glover proposes some ways to gradually weaken the grip of this psychology.

Completed as casualties mounted in the latest political and humanitarian crisis, Israelis and Palestinians is essential reading for anyone concerned by the ongoing violence in the Middle East.

Jonathan Glover is one of Britain's leading moral philosophers. He is Emeritus Professor of Ethics at King's College London, where he also served as Director of the Centre of Medical Law and Ethics, and previously taught at New College, Oxford. His many books include Choosing Children: Genes, Disability and Design, Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century, and Alien Landscapes?: Interpreting Disordered Minds.

Jonathan Glover is one of Britain's leading moral philosophers. He is Emeritus Professor of Ethics at King's College London, where he also served as Director of the Centre of Medical Law and Ethics, and previously taught at New College, Oxford. His many books include Choosing Children: Genes, Disability and Design, Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century, and Alien Landscapes?: Interpreting Disordered Minds.

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Part One: The Cycle of Violence

Chapter 1: Disputed Homeland

Chapter 2: Wounds and Backlash

Chapter 3: Breaking the Cycle?

Chapter 4: Joining the Conversation of Mankind

Part Two: Backlash

Chapter 5: The Psychology of Backlash

Chapter 6: The Illusions of Backlash

Chapter 7: Collective Guilt: The Role of Stereotypes

Part Three: Rigid Beliefs and Identity

Chapter 8: The Role of Rigid Beliefs

Chapter 9: Belief Systems: Challenge and Response

Chapter 10: Identity Traps

Epilogue

Notes

Index

'What singles this book out from all others about the conflict are two features: a sympathetic recognition of the traumas on both sides, but, more importantly, a deeper attempt to unravel and suggest ways to overcome the underlying and by-now self-perpetuating psychological forces that make peace today improbable. This is not a narrative that offers us a ready template for a "solution" in the classical sense: it is a call for what needs to be done to make what is now an improbable solution a possible one. For me, it was an eye-opener!'

Sari Nusseibeh, President Emeritus, Al-Quds University

'Israelis and Palestinians is a book about a land and its tormented politics, but it is first and foremost about people. Jonathan Glover's humanist perspective avoids the common pitfalls of assigning blame or proposing "out-of-the-box" solutions to the indefatigable conflict. His empathetic account of the social and psychological barriers to peace is indispensable for anyone interested in understanding the conflict, let alone solving it.'

Assaf Sharon, Molad, The Center for the Renewal of Israeli Democracy

"deeply relevant [...] With insight and understanding, Glover merges philosophy with psychology, arguing that atrocities are committed because of deeply embedded human tendencies."

Gabrielle Rifkind, The Guardian

"Glover's stature as a moral philosopher affords a unique and valuable perspective."

The Critic

1

DISPUTED HOMELAND

The Israel–Palestine conflict is one of the world’s most intractable. Some say it goes back to 1948 when the State of Israel was recognized by the United Nations. Others say it goes back to the early twentieth century. Others point to nineteenth-century roots. Some push it back as far as the destruction of the Temple in Roman times. This competition over dates is not important, though the history is. What really matters is trying to help reduce the conflict. This chapter starts with three of its related central features: exile, land and home.

I: Exile

In the Israel–Palestine conflict much on both sides is coloured by exile. Jewish experience of this goes back to biblical times: By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?1

Long after biblical times, Jews experienced rejection and murder for many centuries before the Nazi genocide.

The Palestinians do not have that history, but they have never had self-government, and their exile is recent and current. Many were driven by Israeli force from their homes in towns and villages into a stateless limbo. Mourid Barghouti described the impact of this. It stretches before me, as touchable as a scorpion, a bird, a well; visible as a field of chalk, as the prints of shoes. It is a land, like any land. We sing for it only so that we may remember the humiliation of having it taken from us. Our song is not for some sacred thing of the past but for our current self-respect that is violated anew every day by the occupation.2

Those staying in Israel find that state moving towards one where Jews have protected national identity but Palestinians do not.

Palestinians and Exile: Two Memories

Ghada Karmi was a child when her family fled Jerusalem, fearing massacre as at Deir Yassin, where survivors told of mutilation, rape and murder of pregnant women.

Twenty of the men were … paraded in triumph around the streets of the Jewish areas of Jerusalem. They were then brought back and shot directly over the quarries … into which their bodies were thrown. The surviving villagers fled in terror, and the empty village was then occupied by Jewish forces. The worst of it was that the gangs who had carried out the killings boasted about what they had done and threatened publicly to do so again. They said it had been a major success in clearing the Arabs out of their towns and villages. … We never set eyes on Fatima or our dog or the city we had known ever again … our hasty, untidy exit from Jerusalem was no way to have said goodbye to our home, our country and all that we knew and loved.3

Mourid Barghouti reflected on his brother’s exile: Take me to the home of Hajja Umm Isma’il, to houses I have lived in and paths I have trodden. Here you are: treading them again – as Mounif could not, Mounif, who lies now in his grave on the edge of Amman. Being forbidden to return killed him. Three years ago they sent him back from the bridge after a day of waiting. He tried again a few months later and they sent him back a second time. My mother, three years after the event, cannot forget her last moments with him on the bridge. He was desperate to get back to the Palestine that he had left when he was just eighteen years old … His sudden death was the great deafening collapse in the lives of the whole family. He had arrived at this final gate but it had not opened for him.4

Israelis and Exile: Two Memories

On the night when the United Nations had voted to recognize Israel, Amos Oz’s father whispered in the dark to him about being humiliated by other children at his school in Vilna. Amos Oz’s grandfather went to complain. The bullies attacked him too in the playground, forcing him to the ground and removing his trousers: the girls laughed and made dirty jokes, saying the Jews were all so-and-sos, while the teachers watched and did nothing, or maybe they were laughing too. Amos Oz’s father went on: from now on, from the moment we have our own state, you will never be bullied just because you are a Jew and because Jews are so-and-sos. Not that. Never again. From tonight that’s finished here. For ever. Amos Oz sleepily reached out to touch his father’s face, but instead of his glasses my fingers met tears.5

David Grossman remembered silence. My generation, the children of the early 1950s in Israel, lived in a thick and densely populated silence. In my neighbourhood, people screamed every night from their nightmares … when we walked into a room where adults were telling stories of the war, the conversation would stop at once. Daily on the radio for ten minutes they read names of people seeking relatives lost in Europe. Every lunch of my childhood was spent listening to the sounds of this quiet lament. The Eichmann trial brought another loss: of something deeper, which we did not understand at the time and which is still being deciphered throughout the course of our lives. Perhaps what we lost was the illusion of our parents’ power to protect us from the terrors of life. Or perhaps we lost our faith in the possibility that we, the Jews, would ever lead a complete, secure life. And perhaps, above all, we felt the loss of the natural, childlike faith – faith in man, in his kindness, in his compassion.6

Shared Themes

Palestinians know what they have lost. This must be bound up with despair. Israel, with huge financial and military support from the United States, is a regional superpower. The chances of its defeat by its Arab neighbours are extremely small. Despair mixed with a sense of injustice is a recipe for bitterness.

Many centuries of antisemitism make Israelis reluctant to trust their security to others. The effects of the Nazi genocide go down the generations. Those who lose faith that Jews can ever lead a complete secure life, or in human kindness and compassion, may well lack the trust needed for peace. Nightmare happenings in nearby countries must feed fears of what might happen to them if Israel relaxed its bristling toughness. For many the dread behind the toughness must be huge.

Few are pleased by reminders that experience of exile is common to both sides. Jewish Israelis rightly say that the Palestinian experience is nowhere near what the Nazis did to Jews. Palestinians ask why they should have been forced out because of what others did. But there are shared themes. Ghada Karmi’s parents kept the departure from the children. David Grossman’s family fell silent when the children came in. These adults might have understood each other. Mourid Barghouti wrote that Palestinians sang about their homeland only to remember the humiliation of having had it taken from us. This might have been understood by Jewish exiles in ancient Babylon hanging up their harps on the willows. Barghouti’s song is also for our current self-respect that is violated anew every day by the Occupation. Violated self-respect is something Amos Oz’s family also knew.

II: Land

Some Israelis say their ownership of the land comes from 70 ce, when the Romans under Titus destroyed Jerusalem and exiled the Jews. The claim has been doubted. Did the huge Jewish diaspora come from that expulsion? Shlomo Sand says the Romans never deported whole peoples, and that Galut, now translated as ‘exile’, often referred to subjugation. He argues that emigration by an inland agricultural people does not easily explain the many thriving Jewish Mediterranean communities. The trickle of emigrating Jews could not have grown into hundreds of thousands, let alone millions. Sand’s own account of the numbers cites large-scale conversions. After the Persian defeat by Alexander the Great, Mediterranean culture became less tribal and Judaism became less exclusive. Some conquered peoples were forced to adopt Judaism. Converted Gentiles led to 7 or 8 per cent in the Roman Empire being Jews. Sand (whose own views have been disputed by geneticists) says that, without this impact of Greek universalism, there would be about as many Jews as Samaritans.7

It is hard to see where truth lies on this. But how much hangs on it? If Sand is right, does an important part of Israel’s claim to the land collapse? Or, putting the same question another way, if the ancestors of modern Jews were exiled from their land by the Romans, would this support a modern claim to own the land?

As a thought experiment, imagine a family in England who farm a piece of land they have owned for generations. A Danish family arrives, having impressive evidence that, before the Norman Conquest, their ancestors owned the land until the Normans drove them out and took it. The reluctant English family come, rightly, to accept the evidence. Should they hand over the land to the Danish family?

Should the earlier claim trump the later one? Current legal thinking suggests not. The English ancestors legally bought ownership, which includes the right to pass on their property. Unlike renting, ownership brings security. Trumping by unexpected historical claims would make all current ownership (a little bit) less secure. Many...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.12.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Ethik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | ethics • Ethik • Frieden • Frieden, Krieg u. gesellschaftliche Auseinandersetzungen • Glover • Israel • israel and palestine • Israelis • israelis and palestinians • Jonathan Glover • Middle Eastern Politics • Moral Philosophy • Palästina • Palestine • palestinians • peace and conflict • Peace and Conflict Studies • Peace, War & Social Conflict • Philosophie • Philosophy • Philosophy of conflict • Philosophy Special Topics • Political Conflict • Political violence • Psychology of Conflict • Religious violence • Sociology • Soziologie • Spezialthemen Philosophie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-5979-5 / 1509559795 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-5979-4 / 9781509559794 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich