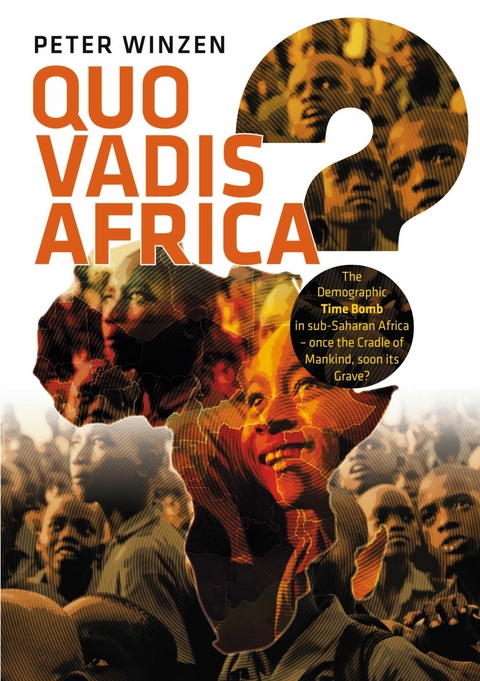

Quo vadis Africa? (eBook)

256 Seiten

Books on Demand (Verlag)

978-3-7583-9798-1 (ISBN)

Der Autor ist promovierter Historiker und bereits mit mehreren Publikationen zur wilhelminischen Geschichte hervorgetreten. In der Fachwelt hat er sich als Bülow-Experte einen Namen gemacht. Geboren am 23.6.1943 in Parsberg/Oberpfalz. Nach dem Abitur 1963 Studium der Geschichte, Anglistik und Politischen Wissenschaften in Heidelberg und Köln; Staatsexamen 1969; Promotion an der Universität Köln 1973. 1974/75 Leverhulme Fellow an der Universität East Anglia/Norwich. 1976-1998 im höheren Schuldienst. Bis 2003 Lehrauftrag für Didaktik der Geschichte am Historischen Seminar der Universität Köln. 1989-2002 wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter der Historischen Kommisssion bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Prologue

Many years ago, the demographers of the United Nations sounded the alarm: since the 1990s, the world population has been growing by an average of 82 million people a year, which is roughly equivalent to the population of Germany. But this also means that the earth’s population is increasing by 1 billion people every twelve years. Until the eve of the Industrial Revolution, global population development was still relatively calm: in 1800, the world population was just an estimated 1 billion. By 1950, it was already 2.5 billion people. Since then, there has been a steep rise in the population curve, which reached its first peak in the mid-1960s (see Diagram 1). Today (2023), the world population already comprises 8 billion people. According to the UN’s median population projection, there will probably be 9.7 billion people on earth in 2050 and as many as 11.2 billion by the end of this century. This naturally leads to the anxious question of how many more people our – from a space perspective – “blue planet” can cope with.

More than 90 percent of the global population increase is taking place in third-world countries and fast-developing nations. While Europe has been stagnating in terms of population for some time, birth rates in Africa are at an astonishingly high level thanks to an average fertility rate of (2018) 4.6 children per woman. In many sub-Saharan African countries, the annual population increase is well over 3 per cent. For example, the desert state of Niger has more than doubled its population in the last twenty years (from 9,799,000 in 1997 to 20,673,000 in 2016), while in the same period the oil state of Nigeria has increased its population from 117,597,000 to 185,990,000. The predictions are even more stirring: according to a recent UN estimate, by 2050 Nigeria, which had a population of just 37.8 million as recently as 1950, will have 401 million inhabitants, and by 2100 as many as 733 million, soon ranking third among the world’s most populous states after India and China. How the African states south of the Sahara will deal with the growing population pressure is written in the stars.

In 1950, 227.8 million people lived on the African continent and its offshore islands. Today (2020) there are already 1,340.6 million. While the population increase on the other continents will slow down noticeably or even stagnate in the coming decades, the population figures south of the Sahara are literally exploding. The African population is expected to double in 2050 (2,489.3 million). By the end of our century, some 4.3 billion people will live there, unless they disperse to other continents, especially Europe, in a huge, historically unprecedented wave of migration. It is hardly likely that these mass migrations will proceed peacefully in the age of climate change. Whereas after the end of the Second World War only one in ten of the world’s population was African, by 2100 one in three people will be African (see Chart 2). Nigeria alone, although barely three times the size of Germany in terms of area, will have almost twice as many inhabitants as the European Union, if the expected mass exodus to Europe does not materialize.

Although these figures suggest a bleak future scenario, the problem of the population explosion in sub-Saharan Africa is hardly reflected in the public discourse. In view of the almost weekly refugee dramas in the Mediterranean, the German government under Chancellor Angela Merkel has taken it upon itself to fight the causes of flight, but when listing the causes of flight, there is almost regularly no reference to the rapid population increase in almost all sub-Saharan states, which, along with climate change, are the real breeding grounds for the numerous famines, the flight movements destabilizing the northern world of states and the intolerable civil war-like conditions in West, Central and East Africa. For ethical, religious and international law reasons, the political elites of the highly developed countries, as well as the most important media, keep quiet about the population issue or at best mention it only in passing. After all, the commandment to “grow and multiply”, which still made sense for the time around the birth of Christ, is part of the core of Christian teaching. And the right to decide for oneself how many children to have and when to have them is a guaranteed human right – first formulated in 1968 at the UN Human Rights Conference in Tehran and reaffirmed in 1994 at the UN International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo. But at the time, the implications of these resolutions were obviously not yet overlooked.

Among Africanists and even among many demography experts, the topic of the population explosion in sub-Saharan Africa (49 out of a total of 54 African states), unprecedented in world history, still does not seem to have arrived, as shown, for example, by Leonard Harding’s treatise “History of Africa in the 19th and 20th Centuries”, designed for students of history. Whereas the renowned researcher still gave a concise overview of “Approaches to the Study of Population Development” in the 1st edition of 1999 under the heading “Basic Problems of Research”, he does not include this topic at all in the third edition of 2013: he has simply deleted this chapter instead of bringing it up to date.

The aim of this study is to trace population development on the African continent from its beginnings to the present day as accurately as possible and, as far as the rather scanty sources allow, to focus on the causes for the respective increase, decrease or stabilization of the population in the different epochs and regions of the continent. In examining the pre-colonial period, the main question is which basic patterns of social coexistence were dominant at the time, in order to perhaps discover parallels to today’s political, social and cultural phenomena. The main aim is to work out mental continuities that also survived the colonial era in order to contribute to a deeper understanding of today’s problems in Africa, which are by no means disregarded in African studies. Using the example of a few particularly conspicuous sub-Saharan states (Congo-Kinshasa, Nigeria, Uganda, Central African Republic and Sudan as representative of the crisis-ridden post-war history of most African states), the eventful political, economic and socio-cultural development of Africa after the Second World War is traced in due brevity. However, this overview does not ignore success stories, such as those of Botswana and Mauritius. The human, political and economic situation in the crisis regions of sub-Saharan Africa, all of which are suffering from a population explosion that has gone largely unnoticed by the world public, is then vividly brought home to the reader on the basis of current reports. The focus is on the search for the reasons for the slide of many sub-Saharan states into permanent crisis mode (systemic corruption, outflow of capital from Africa, misappropriation of the handsome development funds by the elites, lack of willingness to invest, little sense of the political elites for the welfare of the people, rampant poverty, ethnic and linguistic diversity, permanent threat to the population by heavily armed rebel militias with an ethnic background and, last but not least, the growing population pressure that is already overburdening most sub-Saharan states). Particular emphasis is placed on the fact-oriented elaboration of the various factors for African population dynamics and repeated reference is made to the consequences of overpopulation that are already beginning to be observed. Finally, an attempt is made to outline possible strategies to curb population growth, as they have been suggested from time to time in journalism and are still awaiting a broader public discussion.

There is hardly a humanities discipline that is fraught with so many controversial positions as African studies. This is shown by the debate on the evaluation of the colonial era alone, which – depending on the political-ideological orientation of the scholars – ranges from absolute condemnation (“the greatest crime in world history”) to well-differentiated positive judgements, which in turn are met with great indignation by some Africanists. Prejudices and taboos often obscure the reality of the current situation in Africa. Nevertheless, many academics spread a rather positive image of Africa, precisely because they are probably bound by certain taboos. For example, during a public lecture on Africa today, an audience member asked the speaker, a professor of African studies, about the problem of the numerous civil wars and child soldiers, and she frowned and said: “That’s racism”.

For many homosexuals, for example, Africa is still a dark continent. Homosexuality is punishable in 34 of the 54 African states, and in two of them – Mauritania and Sudan – proven homosexuality is even punishable by death. In Uganda, homosexuals face life imprisonment on the basis of a penal code article dating back to the British colonial era, which stipulates that same-sex sex is “against the natural order”. For some parliamentarians in this East African state, this article does not go far enough: they announced that they would introduce an amendment to the law in the House of Representatives that would even provide for the death penalty for homosexuals in individual cases. Already eight years ago, a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.12.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung |

| ISBN-10 | 3-7583-9798-7 / 3758397987 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-7583-9798-1 / 9783758397981 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich