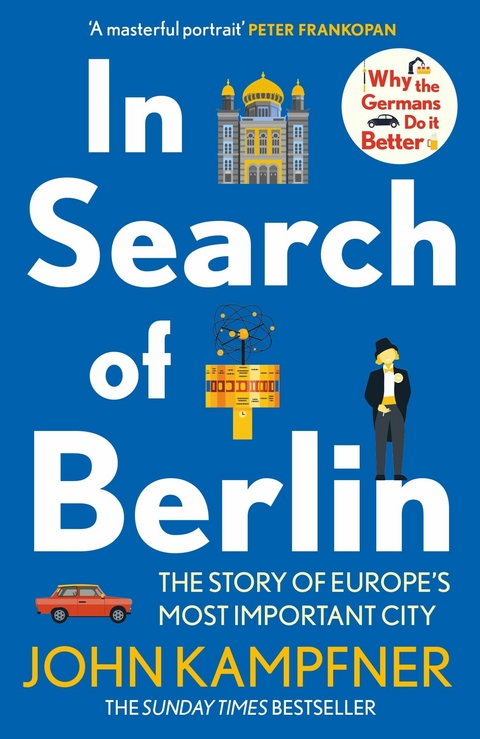

In Search Of Berlin (eBook)

416 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-483-3 (ISBN)

John Kampfner is an award-winning author, broadcaster and foreign-affairs commentator. He began his career reporting from East Berlin (during the fall of the Wall) and Moscow (during the collapse of communism) for the Telegraph. After covering British politics for the Financial Times and BBC, he edited the New Statesman. He is a regular TV and radio pundit, documentary maker and author of six previous books, including the bestselling Blair's Wars. His most recent book, Why the Germans Do it Better, was a top ten bestseller, Book of the Year in the Guardian, Economist and the New Statesman, and sold over 100,000 copies in all editions.

John Kampfner is an award-winning author, broadcaster and foreign-affairs commentator. He began his career reporting from East Berlin (during the fall of the Wall) and Moscow (during the collapse of communism) for the Telegraph. After covering British politics for the Financial Times and BBC, he edited the New Statesman. He is a regular TV and radio pundit, documentary maker and author of six previous books, including the bestselling Blair's Wars. His most recent book, Why the Germans Do it Better, was a top ten bestseller, Book of the Year in the Guardian, Economist and the New Statesman, and sold over 100,000 copies in all editions.

Introduction

I cannot get Berlin out of my mind. I have been living in it and coming to it for more than thirty years, first as a young journalist based in the communist East watching the dramatic events of 1989–90 and up to the present day, as the city is confronted by a new version of European conflict.

It is a place where traumas are unleashed. It is also where the traumatized gather.

The city’s scars are a source of inspiration and a testament to the power of reinvention. Berlin is a laboratory. Even people who have spent brief periods in the city feel it is part of their lives. I certainly do; that is why I keep coming back.

For much of its existence, Berlin has been dismissed as ugly, uncultured and extreme. After the fall of the Wall, it was expected to become more ‘normal’. Start-up entrepreneurs from around the world have been making it their home, providing the first significant economic activity for a long time. Gentrifying Germans from the south have arrived, supposedly bringing with them bourgeois respectability. Yet Berlin is still a mess. It cannot run its own elections properly and often fails to provide basic services. You can’t get a death certificate, you can’t get a birth certificate, people complain. It is schmuddelig (grubby) and often abrupt. It is a hotchpotch of architecture and a city planning nightmare. It is one of Europe’s most sparsely inhabited capitals and yet it suffers one of its most acute housing shortages, a problem it has struggled with for centuries. For decades its standard of living has been below the national average. The city has few natural resources, no manufacturing to speak of and not much wealth.

Berlin has stumbled from enlightenment to militarism, from imperialism to democracy to dictatorship, from village to world city to surrounded island. It has been a trading post, military barracks, a centre of science and learning, industrial powerhouse, a hotbed of self-indulgence and sex – and control centre for the worst experiment in horror known to man. It was at the heart of the Cold War, the front line of communism and hang-out for hippies and draft-dodgers. It has been the site of three failed revolutions and one extraordinarily successful popular uprising.

No other city has fretted so much about its status. No other city has had so many faces, so many disasters and has reinvented itself so many times. No other city is so confused about itself and what it imagines itself to be in the future. Berlin is tortured by its history and yet many buildings look as if they have no history. Each site, almost each paving stone, has lived many lives, each era superimposing itself on the one before. Each plague, each fire, each war, each act of destruction and self-destruction, requires it to start again.

‘Berlin is a place you project yourself onto,’ says David Chipperfield, the British architect who has left his stamp on the city, with his re-imagining of the Neues Museum and the Neue Nationalgalerie. ‘Berlin is not really there. It’s an idea. It’s been a Prussian idea of a metropolis, a Nazi idea, an Allied idea, an East German communist idea, and more recently a young people’s idea. It’s not a completed masterpiece, but a canvas on which different generations have painted.’

Its shortfalls are tangible. It is unloved by those who fail to understand it. Its draw is more ephemeral and harder to identify. But when you ‘get’ Berlin, it seeps into your skin.

When he was made an honorary citizen of Berlin, the German president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, reminisced about doing his doctoral thesis there in 1989. A decade later, the removal vans brought his family’s belongings from Bonn as parliament was transferred. While the new government quarter was still being constructed, he spent the first year and a half in the office of the ousted East German leader, Erich Honecker, ‘with a view of the Palace of the Republic and Mongolian goatskin wallpaper in the dark hallway’, improvising each day. He, like so many others down the ages, came to Berlin without understanding it. In a speech in October 2021, he ventured to suggest that he now did: ‘Berlin has throughout its history been a place of longing for those who have found it too cramped elsewhere, who think more deeply, continue to research, reach higher, who want to change things or live differently,’ he said. ‘The alien, the different, the new are not rejected or excluded; they are curiously and hungrily embraced and absorbed; this openness characterises Berlin like almost no other city I know.’

That is why Berlin is a magnet for people from around the world. People know they can leave a mark – and, from Slavs to Jews, Huguenots to Dutch, Russians to Turks, and now Afghans to Syrians, they have. Berlin is the destination of choice for people who want to make a new life for themselves. You can always find your niche in Berlin. Everyone, it seems, comes from somewhere else. Everyone, it seems, has a story to tell.

This is an 800-year history, but an unconventional one. It is a dialogue between Berlin’s past and present, following a broad chronology, identifying the commonalities between the different eras and linking them to the present day.

For centuries, the world passed it by. Its geography and topography spell trouble. All around are sweeping plains, exposed to the Siberian winds. The city seemed to have arrived from nowhere, with no connection to the great civilizations. The Romans ‘civilized’ a number of places in Germania. Not Berlin: they didn’t get this far. The city started late and continued late. It is still not complete. It has always been the upstart, the ingenue. It still doesn’t quite know when it all began, but in Albrecht (Albert), a twelfth-century conquering count known as ‘the Bear’, Berlin has found a motif for all time. In an archive in the once-dominant town of Brandenburg, a piece of parchment provides the first evidence of a settlement built on a swamp, dating back to 1237. Historians take that to mark the start of Berlin – they might as well, there is nothing more definitive – and so it became. Thanks to wars and division, however, much archaeological work remains undone. In recent years, Berlin has been catching up fast, excavating across the old centre in a determination better to understand its origins. Barely a month goes past without an announcement of a new find.

It seems as if each building is contested, none more so than the place where in the fifteenth century a palace was built by a prince dubbed ‘Iron Tooth’. Local burghers, furious with this outsider taking over, opened the weirs, flooding the foundations. That building has lived many lives, most of them unhappy. It was torn down and rebuilt many times, a palace rarely beloved by kings. After the Second World War it was replaced by a monument to socialism, and then demolished after reunification. The present building, the Humboldt Forum, has been the object of every possible insult to which the German (and English) language can stretch.

History leaves its mark wherever I go. I trace a line between the Thirty Years War and the peace movement of today, yet you have to go an hour out of town to see any memorialization of that terrible conflict. A small museum in the old castle of Wittstock tells the story of three decades of bloodshed that took the lives of more people than either of the two great wars of the twentieth century. Only a few miles away, protesters have spent years trying to stop the present-day army from using the land. Pacifism is now hard-wired.

My account is as much a story of memorialization as a history. How to relate to Friedrich (Frederick) the Great in the eighteenth century, who ushered in the (Jewish) Enlightenment of Moses Mendelssohn, and yet called the Jews ‘the most dangerous’ of all the ‘sects’? How to relate to his father, Friedrich Wilhelm I? The man called the ‘Soldier King’ executed his son’s tutor and lover in front of him, loathed his wife and derived pleasure only from hunting. He turned the city into a garrison and yet never fought a war. Across Berlin statues, like buildings, are erected, damaged, removed, revived. The Soldier King stands in a few spots, often daubed with graffiti. By contrast, a statue of Frederick the Great enjoys a prominent spot in the centre of the city, even if it is surrounded by traffic.

Its electors, kings and kaisers wanted Berlin to become a Weltstadt (a world city). Yet only for one period did it manage to match the grandeur of Paris, the economic power of London or the vitality of New York. Even at its peak, Berlin was uncomfortable with itself. The debates around industrialization, rapid growth and inequality are reflected in the fraught politics of housing today. In the Wilhelmine era, from unification in 1871 to the outbreak of war in 1914, Berlin was the scene of conspicuous consumption. Now only the vulgar flaunt their riches, wear flashy clothes or, heaven forbid, talk about property prices. Berliners boast that people are judged, if at all, purely by the power of their ideas.

Berlin exceptionalism: reality, myth, marketing? I look at the role history plays in branding, from Babylon Berlin to Bowie to Berghain. The Weimar era, with which foreigners and Germans are currently obsessed, marked a halcyon moment for science, art and music. The city became a haven for gay people from across Europe and beyond. Berliners like to remind all-comers: the tolerance was confined to a city, not a country. And their memory is...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.10.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Berlin • berlin secrets • bestselling author • Beyond The Wall • Brigitte Reimann • Cities • Europe • Germany • guide to berlin • History • Katja Hoyer • Lonely Planet • lonely planet berlin • Metropolis • resilience and reinvention • Second World War • Sinclair McKay • Stasiland • The Berlin Wall • Travel • Travel Guide • Why the Germans Do It Better |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-483-X / 183895483X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-483-3 / 9781838954833 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 7,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich