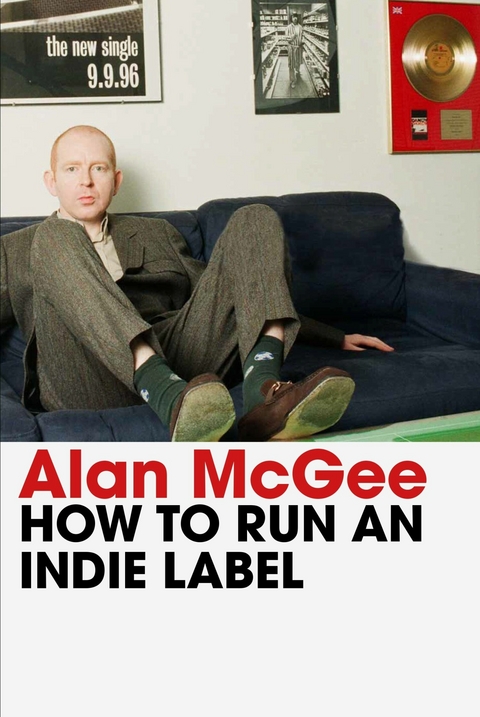

How to Run an Indie Label (eBook)

320 Seiten

Allen & Unwin (Verlag)

978-1-83895-800-8 (ISBN)

Alan McGee is the best-known label boss of the post-punk era. His label, Creation Records, has become iconic launching the careers of bands like Oasis, Primal Scream, My Bloody Valentine and many others. He also manages the Happy Mondays, Ocean Colour Scene and many more. He is brilliantly quotable and has endless anecdotes about his time in music. In a time when music has become safe, he is one of the last of the great mavericks.

Alan McGee is the best-known label boss of the post-punk era. His label, Creation Records, has become iconic launching the careers of bands like Oasis, Primal Scream, My Bloody Valentine and many others. He also manages the Happy Mondays, Ocean Colour Scene and many more. He is brilliantly quotable and has endless anecdotes about his time in music. In a time when music has become safe he is one of the last of the great mavericks.

INTRODUCTION

by John Robb

I’ve known Alan McGee since 1981. It was the tail end of the punk rock wars, a time of post-punk DIY ideology and a belief that we could change the world with three chords and self-released records. We were all making music on our own terms, wild-eyed outlaws who believed in the power of rock ’n’ roll. Anything was possible and the music scene was a wild west full of possibilities and dreams.

It’s been a long and strange journey. Whilst some people made records, others made history.

Some people made both.

Before that, growing up in the pre-punk seventies, no one would have thought of running a record label, let alone releasing a record. That seemed like a supernova glam world, way out of reach of mad music geeks like Alan McGee. Punk rock changed all that. It was empowering and it tore a hole in the cultural fabric and allowed everyone in.

Looking back, decades later, McGee would say of the mid-nineties Britpop years, ‘We all took too many drugs, and my behaviour was quite mad.’ In those post-punk years, however, when everything was possible, he took no drugs but was perhaps even madder. In that time of both grinding political nihilism and thrilling cultural possibility, he was like a whirlwind of energy and enthusiasm, driven to make sense of the world and his own life through music. As we all plotted our own take on this brave new world, he suddenly appeared out of the ether. I couldn’t say no to the vision from this passionate and fiery Scottish voice crackling down the line when I picked up the phone at my parents’ house in Blackpool, where I was living for a few months after being kicked out of Stafford Polytechnic.

I was one of the early people to get the McGee treatment. That tidal wave of spittle-flecked optimism wrapped in a strong Glasgow accent. He was offering my band, the Membranes, a gig in London and would not take no for an answer. We had decided for some long-lost reason that we would never play the capital again. It was the kind of irrational decision that defined the maverick ridiculousness of the then underground music scene as we railed against the then-horrible music-biz stench of the small-gig circuit of the capital. Maybe this was because the gigs in the big city were rubbish – you were treated like fools who were desperate to play in London because, hey, you might get spotted by a label!

Unlike the rest of the country, where there was a spider’s web of thriving local scenes appearing on the back of the fanzine culture, with ’zine editors and music fans putting on gigs and building networks in their towns, the London venues made you feel you were lucky to be allowed to play in their city. They thought it was an honour for desperate bands to drive all the way there and back on the same day for the half-hour set that they often wanted you to pay for. The venues had pick-and-mix bills of bands, and came with grumpy promoters who hated the music. For fresh-faced new bands there seemed to be nowhere in the city that was remotely interested.

We had experienced enough of this London gig vibe in joints where there was no sense of community or scene. Of course, we were not superstars, but we were beginning to build a good following after one of our early 1981 releases, ‘Muscles’, was made single of the week in the music press and played relentlessly by John Peel. We had also just had our first big feature in Sounds music paper, written by Dave McCullough. The late music writer was a firebrand, fixated on the brave new world of post-punk ruckus and like a parallel scribe to the NME’s Paul Morley. They were both seeking out the music future with a wild enthusiasm and ornate and captivatingly pretentious prose, armed with an entertaining and compelling vision about what music could be. Dave was tireless, typing his missives whilst sieving through the post-punk underground of never-ending bands and labels and looking for the gold dust of a new direction in the cultural confusion.

Punk had affected people and made them want to do something – anything – and writers like these seemed like lone wolves, typing extraordinary and thrillingly affected missives about obscure skinny outsiders, many of whom have become unlikely gatecrashers in the mainstream.

In 1981, Dave came up to Blackpool to interview us on the prom surrounded by vicious seagulls and even more vicious grockles. He was bemused by the plastic weirdness of the place, which had nothing to do with us.

In the same period, Dave also wrote about a young Glasgow band, The Pastels, and other youthful angular outfits like Alan McGee’s own early band, The Laughing Apple. He was searching for the holy grail in the fresh-faced guitar youths who were appearing in the post-post-punk hinterland and joining the dots in this fragmented new culture. He was already on the case with the wonderful bands like the caustic snark genius of The Fall to the highbrow pop of Scritti Politti, or the sound of young Scotland – from Postcard Records to the Fire Engines. He was looking for the next narrative in this brave new world. Maybe me, McGee and Stephen Pastel were brief moments of hope before he found his band when he wrote about The Smiths. Once they had been located, music moved into a new phase.

Yet the mavericks that had signposted this journey were too full of idealism and brimming with pop culture to fade away. Whilst Dave was typing, Alan McGee was plotting, and a new bunch of disparate bands were twitching. McGee was savvy enough to spot this. He had just moved to London from Glasgow and was trying to find a space for his band. He was releasing his own records, booking his own gigs and now running his own tiny gig night, and whether by accident or design, he was tearing up the fabric and creating a new pop art future.

Alan had read the interview with us in Sounds and that’s when the phone calls started, which massively entertained my mother who is Scottish and liked hearing this manic accent down the phone whenever she answered.

Eventually, in 1983, McGee persuaded us to play his new night at the Adams Arms on Conway Street in central London. Calling his club The Living Room, the weekly gig was built around the coterie of underground bands he was collecting and who were beginning to create a new scene coalescing around his new night and his Communication Blur fanzine.

These were bands like the Nightingales, The Three Johns, his own band, and especially Television Personalities. The latter’s vision of a high-octane mix of sixties pop art and punk rock would dominate the Creation narrative, from its twitching small roots to Oasis at Knebworth, and that crush collision of sixties beat and seventies punk was the core of what would become the label’s aesthetic. It was this disparate scene of maverick bands playing for the wild-eyed promoter in the tiny upstairs room of a London pub that would construct the foundations of future indie. The smallest of small acorns that would grow into the biggest icons, but somehow it all made sense – these were awkward misfit bands who were not playing anyone’s game, and each had their own vision that would eventually catch fire. Like McGee, they were musical nut jobs who were always seeking something else.

Of course, Alan was the maddest of them all. Like all the best visionaries, he believed. In everyone. He himself was a rock ’n’ roll star but with no perfect vehicle. His own bands were great but they never cut through and he ironically found stardom and escape in being the conduit for everyone else’s dreams.

The Living Room gave us all room to live. The club was a blast and the gig was great. It was rammed with fellow souls and gave us and many other lost souls a step into London.

In the idealistic early eighties, it was the only gig in London where the music heads would turn up and where there was a sense of scene. Also, Alan would pay you properly, with the agreed wedge of money pulled out of his pocket, making him the only person with any business savvy on the scene, as he didn’t drop money on the floor or lose it from a ripped plastic bag like the drunken promoters at other venues. He even saved a bit every week for his new venture – an as-yet-unnamed record label. It all sounds fundamental now, but in the London of the times it was rare to be treated properly and it was rare that anyone had any vision.

From that point on, McGee and I became pals. I would hang out with him in London and we would talk of changing the world one record at a time. We would meet people in the warehouse at Rough Trade and liberate lots of the records in their huge storeroom, selling them to cover train fares and food. Rought Trade didn’t seem to mind. Maybe it was their way of supporting the waifs and strays who made up the indie underground.

In this post-punk hoedown, McGee planned his new label, which he christened Creation after the sixties psych band. I would write about his early label releases in my Rox fanzine and then in Zig Zag magazine, which I had started writing for. I was intrigued by the look of those early Creation records – the Xerox machine folded sleeves inside plastic bags and the pop-art logo on the labels that matched the off-kilter jangle of the music with its punk-rock art ferocity. You could see and feel the love of decibels and the possibilities of guitar pop. There were great songs like The Pastels’ ‘I...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Comic / Humor / Manga | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | Alan McGee • bobby gallespie • Britpop • Creation Records • Definitely Maybe • Glastonbury • Happy Mondays • Jesus and Mary Chain • Liam Gallagher • Noel Gallagher • Oasis • Oasis 2025 • Oasis 25 • Oasis reunion • Primal Scream • Teenage Fanclub |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-800-2 / 1838958002 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-800-8 / 9781838958008 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 768 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich